Image Credit: All photos: David Murakami Wood

Image Credit: All photos: David Murakami Wood After the walls were set, ceiling panels separating the first and second floors are craned into place. They are supported by beams that span the width of the building. Wall, ceiling, and roof panels are delivered precut to their final dimensions. Each panel is fastened to its neighbors with steel screws. Gaskets between panels keep the house airtight. Gable ends complete the exterior walls. Roof panels rest on a structural ridge and are screwed to the top edge of the wall panels. Windows are installed on 2x6 bucks. The rigid wood fiberboard insulation on the outside of the walls is 11 inches thick. These triple-pane windows are heavy. A site-built hoist made installation a little easier. Chases to run wiring, along with recesses for receptacle and switch boxes, are pre-drilled. An Optiwin technician sets a window frame in its 2x6 buck. The Motura tilt-and-slide door is set into place. The door, which the author describes as one of the most expensive things in the house, is "beautiful, and it closes like the door of a safe." It was manufactured by Optiwin. Up and in. Removing the insulation from the outside of the hot-water tank make it less bulky, but it still weighed 419 lb. and had to be maneuvered over the door sill very carefully.

Editor’s note: David and Kayo Murakami Wood are building what they hope will be Ontario’s first certified Passive House on Wolfe Island, the largest of the Thousand Islands on the St. Lawrence River. They are documenting their work at their blog, Wolfe Island Passive House. For a list of earlier posts in this series, see the sidebar below.

Our plan for the cross-laminated timber (CLT) construction process was to do one floor a day. As days are short in December, and darkness comes soon after 4.30 p.m., we started as early as we could.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

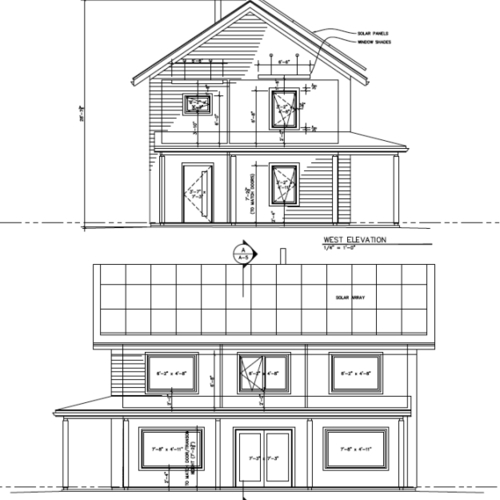

Wall panels are 110 mm thick (about 4 3/8 inches), to be insulated on the outside with rigid wood fiberboard. We started with the west wall, which had to be braced until other walls were put into place. Pieces were moved into position with a crane, and placement was crucial. Every millimeter counted, so the crane operator was a very important part of the team. [Note: See the images below for an abbreviated look at how the building was assembled. For a more extensive photo library, check the Wolfe Island Passive House blog.]

We had the wall and roof panels in a rack and stacked in piles. Keeping the process moving smoothly meant knowing where each one of them was located.

Each external wall and ceiling piece has a gasket on the edge so the structure will be airtight when complete. Each piece is joined to the others with 200 mm (about 7 3/4 inches) steel screws. By the end of the day we had done exactly what we had hoped and planned for: a complete first floor! (See Image #2, below.)

The second day of our build brought another overcast sky but, thankfully, no rain. And we got even more done than we had hoped for (see Image #4, below), so that on the third day we we would only have to install the roof panels (see Image #6), saving a significant amount of money on overtime (for the crane and operator, at least). More important, we will have managed to do what fully trained crews in Germany and Austria do in just about the same amount of time.

So, in two and a half days we completed the main CLT structure, and also tidied and rearranged the site to be ready for the next week’s work. Everyone did a fantastic job. A special thanks goes to Mike, the crane operator from C.A. Peters. He had to switch constantly between being bored for long periods of time and then having to do precision lifting. All the while he dealt with a whole lot of different people, not all of whom were experienced with big cranes and the signals needed for their operators.

A week of windows

The crew moved all of the windows into the house in preparation for the installation, and continued to build and install the 2×6 outer frames that would help support the windows in the insulation layer (see Image #7, below). Tomaz, a technician from Optiwin, the window manufacturer, flew in to train and supervise our crew.

The windows are placed at a point roughly midway through the wall. The windows themselves are fairly deep, with the outer pane about 1 1/2 inch beyond the bucks. We put the windows as far out as we could given their weight, and made the calculations in the Passive House Planning Package (PHPP) in terms of any differences in solar gain.

The total wall thickness is 17 inches: about 4 1/2 inches for the CLT, 11 inches for the insulation, and about 1 1/2 inch for the air gap and the siding. The outside of the windows are 10 1/2 inches from the inside of the wall structure.

We started with easily liftable windows to get the techniques right before moving on to the bigger windows. We left the really big ones for the following day (see Image #8, below).

It was a miserably wet night and the house was filling up with water. Despite protecting all the window openings and sealing many of the gaps, the areas where the walls join the roof and the floors had not been sealed, and rain was infiltrating everywhere.

We didn’t have time to do more than vacuum up the worst areas as we still had a lot of windows to install. The rain continued throughout the morning until it turned to misty drizzle by the afternoon, which was the best kind of weather for installing windows. But, working into the darkness, we got all of them done except the long window over the stairs and the big tilt-and-slide door.

The last day of window installation was much drier than the previous one! Our architect, Malcolm Isaacs, had been intending to take Tomaz back to Wakefield before heading down to Montreal Dorval Airport, but since we still had the big Motura tilt-and-slide door to do, they insisted on staying until they had it finished (see Image #11, below), and then headed directly to Dorval to get Tomaz on the plane.

And now for some heaving lifting

The delivery of our Wallnofer Walltherm stove, water tank, and solar thermal panels had been delayed by bad weather along the route from Nova Scotia, and we were not expecting them quite as soon as they arrived. We got just an hour’s notice at lunch that they would be arriving on the next ferry. It was barely enough time to get the backhoe/fork-lift.

With the three pallets off the delivery truck, we faced the difficult job of getting the very heavy water tank, and even heavier stove, into the house. Because of the shipping delay, the doors had already been installed, meaning that clearance was limited. Luckily, the water tank’s insulation is designed incredibly conveniently so it zipped off. The tank itself was still 190 kg. (419 lb.), and big, too, but four of us managed to pass it over the sill of the tilt-and-slide door and get it onto a flat trolley inside the house (see Image #12, below). We could then move it into the utility space.

The stove was smaller but, unbelievably, even heavier. We partly disassembled it, removing doors and as many of the fire bricks as we could, but we probably did not reduce its 300 kg. (661 lb.) by any more than 10%. To get it into the house and over the sill, Chris thought up an impromptu ramp and bridge. With two people pulling, two pushing, and all of us watching the balance of the stove, we managed it.

9 Comments

CLT

Did you have trouble finding a crew to install the CLT? Or was it really as easy as IKEA furniture. Do you know of any resources for CLT spans/thicknesses from US manufacturers? Why did you go with Austrian CLT instead of Canadian?

2x6 bump outs?

Talk about thermal bridging. I wonder why thinner board wasn't utilized. It's not like the windows aren't attached with straps.

Window details

Chris, I'd be interested to see the window installation details with CLT and all that external insulation.

David,

Thanks for the post.

David,

Thanks for the post. What is the total BTU's of the stove? I believe their website says about 30% of those BTU's will be given off as radiant heat. Did you need to purchase their kit for super-insulated homes which reduces the radiant heat output?

Chris/Ethan - It appears as if the entire window is laying in the 2x6 buck so I don't know strapping or a plywood buck was an option. Plus the total distance from the outside of the 2x6 to the inside of the CLT is almost 10" so that is an R-12ish. They may have also over insulated the front of the 2x6 as their is an additional 5.5 inches of insulation outboard of the outer edge of the 2x6.

Answers to questions

Hi everyone,

I'll try to answer the questions in order...

1. Did we need a special crew?

Well, yes and no. Our builider is a guy called Chris Vanderzwan from New Leaf Custom homes in Kingston, ON. He's a specialist in sustainable homes, and has studied passive house design, as has our architect and advisors. He was also a carpenter before becoming a house-builder and so he really understands wood. Which has been invaluable. Plus, finally, he is an incredibly careful person, who put hours into reading the engineering documents and understands the process. In addition the whole process was overseen by Malcolm Isaacs of CanPHI whose company, Construction Maison Passive is the importer for most of the components we used. So we had specialist help, but actually, our 'untrained' crew demonstrated that any competent builders, and even non-builders like me (I took three days off my day job to be part of the crew for this) can manage a CLT build. Whatever else about the process is specialised and problematic, that's a really key lesson for anyone else considering this.

2. Thermal bridging.

I think you've misread what's going on here, Chris_M. As Jonathan Lawrence observes in post #4, the bucks are ultimately entirely embedded within the outer inuslation. There is no single piece of wood that connects from inside to out. I'll try to dig out a diagram for you all.

3. Why not Canadian CLT? Partly because we went with the supplier concerned as an experiment in testing their business model in return for free consultation and advice. Partly because we looked at available Canadian CLT quality in comparison, especially in the factory-cutting specification, and found it lacking. Things are changing rapidly, however. If we were starting now, knowing what we now know, we'd almost certainly go local. See this recent post on our blog, that takes you through our thought-process: https://wolfeislandpassivehouse.wordpress.com/2016/08/09/how-we-got-started/

4. The stove. Ah, therein lies a story, which I am sure will be told in a future GBA blog entry. Suffice it to say, that we aren't installing it after all, and we have the world's best hydronic wood stove for sale to those who want it, at a very reasonable price - contact me if you are interested!

I should also note that there's an error in the picture captions. The Motura door is made entirely by Optiwin. It's the front door that is both expensive and made by Tarredo.

Response to David Murakami Wood

David,

I'm sorry about the error in the caption. I have corrected the error. Thanks for letting us know.

Time-lapse of the CLT building process

I should mention that there is a fantastic time-lapse film of the entire CLT construction process on the CanPHI website here: http://www.passivehouse.ca/project/murakami-wood-passive-house

Rain

How did the rain effect the CLT? Are you going to have the CLT exposed on the inside? If so did the rain water stain it?

Rain

Ah, rain. Not my favourite word. I think there may be a future blog here about the various problems we had and changes we made - but if you want the preview, you can take a look here - short version, yes, it's a problem and you should wrap your CLT immediately after construction: https://wolfeislandpassivehouse.wordpress.com/2016/01/10/rain-and-clt/

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in