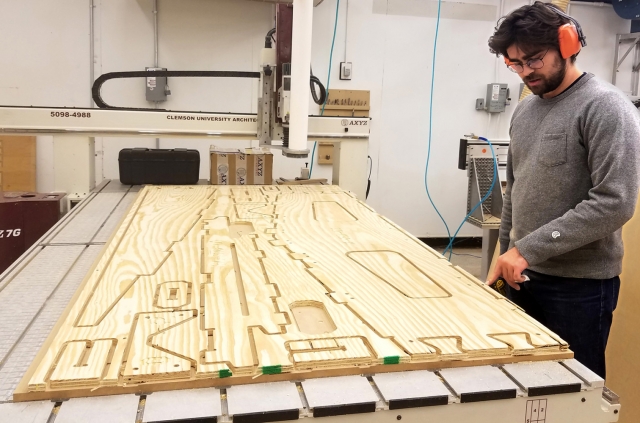

Image Credit: Clemson University

Students and faculty at Clemson University’s School of Architecture are developing a framing technique that will allow buildings to be assembled rapidly from pre-cut plywood components with a minimum of tooling and using mostly unskilled labor.

According to a post at Clemson’s website , the “sim[PLY]” building system grew out of the university’s 2015 Solar Decathlon entry. Plywood components are cut to shape with a CNC router and can be shipped to the building site flat. Developers say assembly, which relies on slot-and-tab plywood connections and stainless steel zip ties, is intuitive.

“With a click of the button, someone could order a custom-cut, flat-packed home online and construct it by hand with the help of their friends and neighbors in a matter of days,” said Kate Schwennsen, professor and director of the School of Architecture.

One advantage of the sim[PLY] approach, the university says, is that digital construction plans could be emailed to any shop equipped with CNC tooling, and building pieces cut out of standard sheets of plywood. The components can be assembled without the need for power tools or heavy equipment. Buildings can be taken apart as easily as they are put together without damaging the components.

Houses assembled from prefabricated panels aren’t new. But the idea that a buyer could source components manufactured from off-the-shelf materials thousands of miles away from the company that designed them is a significant departure from what’s on the market now.

Roots in a student design competition

Lots of innovative building ideas are tested at the Solar Decathlon, a student design competition for solar-powered buildings sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy. Students and their faculty and industry partners get a chance to try new ideas in what are essentially one-off designs. Once the competition is over, the houses are typically taken apart, packed up and shipped back to campus where they become living labs, exhibits, or sometimes just gather dust in storage. But in this case, the Clemson Decathlon team is trying to turn its ideas into a full-fledged, marketable building system.

Daniel Harding, an architecture professor at Clemson who led the design and building team for the Solar Decathlon house, said a sim[PLY] building resembles a conventionally framed building with bottom plates, studs, and roof trusses and other familiar components. The difference is that parts are milled from 3/4-inch, off-the-shelf plywood, and held together not with nails but slot-and-tab connections and stainless steel zip ties.

Plywood framing is on a conventional 4-foot grid, but stud spacing can vary from just under 2 feet to about 1 foot, depending on the loads the walls will be subjected to, Harding said. Studs look like Larsen trusses, a design that simplifies plumbing and wiring runs while reducing thermal bridging.

Finding an alternative to the nailed connections in conventional framing was key, Harding said in a telephone interview. Without nails, said the former general contractor, there are no nail guns, no compressors, and no need for air hoses and extension cords. Instead, zip ties hold plywood components together until structural loads are absorbed by the completed assembly. That reduces waste, improves job site safety, and makes it just as easy to take the building apart as it was to put it together.

“The idea was that if we can reconfigure the way the wood is put together, to use a different metal connector, we can use the metal to hold the building together rather than a compressive spike in shear. We redesigned our whole system around how we would use metal and fasteners differently,” Harding said. “It follows the logic very similar to that of traditional light wood framing in that there are studs, there are sill plates connections, and hold downs — very similar to platform framing. It’s just the work is being done with the way these plywood parts are designed and held together with stainless steel zip ties.”

A sim[PLY] building also gains some strength from the screws used to attach sheathing — Huber’s Zip system sheathing in the case of the Solar Decathlon house.

A number of challenges remain

The system isn’t ready for use on a wide scale just yet. Clemson builders have so far put together just four buildings, including the Solar Decathlon entry that will be repurposed later this year as an affordable housing unit in South Carolina. And the group is still working on some sticky technical issues.

Among them is the maximum length of building components, currently limited to 8 feet because parts are cut from standard sheets of 3/4-inch plywood. Until the team designs and tests splices to connect components, buildings will be limited to one story in height. Harding says the group will be working on plans for a multi-story building and already has developed some simple prototypes and models for the connections that will allow the system to grow beyond its current limits.

Code acceptance is another potential issue, although Harding says building officials Clemson has worked with so far have been receptive and approved the designs for occupancy. In the 2015 competition, for example, Clemson had to meet California’s code requirements for a public assembly structure, and buildings now in use in South Carolina had to pass muster with building officials before they could be used. In all, Harding said, the framing system is equal to or better than conventional light wood framing.

Higher costs could be a problem with some buyers. Harding says a sim[PLY] building could be competitive in price with a conventionally framed structure, providing a good CNC shop was handy to the building site and reduced labor and tooling is figured into the equation. It’s probably safer, however, to assume a plywood-framed building would cost more. Marketing the system successfully will mean convincing buyers the system’s advantages are worth it, and that may be easier to do with DIY builders than it would with a production builder.

“Right out of the gate it’s going to be more than the price per square foot of just a stick-framed house,” Harding said. “What doesn’t come into effect is that it’s done in eight days instead of 30 days. It’s done with almost no trash on site. It’s done without a temporary power pole. It’s done with no tools that anyone has to invest in. And the performance of the house is so much higher than a stick-framed house.

“We’re trying to figure ways to make marketable the benefits of the cost when it’s looked at in a more holistic, comprehensive process,” he said.

What the buildings might be used for

Clemson developers thinks sim[PLY] would be ideal for owner-built houses, and particularly tiny houses. Architectural students have come up with a tiny house prototype that could be framed in a single day, and the university says the U.S. Defense Department has looked at sim[PLY] buildings for possible use as temporary housing. Italian officials looking for temporary housing options in regions affected by earthquakes have been in touch with the school.

Harding, however, says the goal is to develop a building system with many applications, not just disaster-relief or worker housing. To that end, Harding said the group is seeking patents on the process, although there are no plans to spin off sim[PLY] into an independent company beyond the Clemson University umbrella.

“Our interest is not necessarily to put a specific product on the market,” he said. “I think our objective is to say here’s a really safe, intelligent way to build that’s sustainable. We think we can capitalize on labor and material.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

2 Comments

interesting but ...

Great to see people thinking about other approaches. But if it's more expensive, it's probably not going to be adopted. And it also looks like all the stuff that actually takes time on site--plumbing, electrical, air sealing, insulation, window and door installation, etc., is not any different. I am suspicious that they are starting with the cool CNC tools they have and looking for a way to use them, rather than starting by observing (or better experiencing) conventional construction and identifying what the pain points are and trying make improvements there.

Charlie

Alastair Parvin has a very persuasive Ted Talk in which he lays out the problems of third world housing, and the lack of democratic methods of building which would allow more DIY construction. Then - just then you expect him to champion vernacular forms and local materials - suggests that the solution is for some reason to give everyone software and CNC machines.

The same optimism swirls around 3D printers. These new technologies are very seductive - especially to students.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in