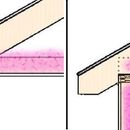

Weird top-plate area idea

New England is going through a helluva winter, and has turned into

a festival of ice dams across much of the Northeast.. [Go here for

a small artistic study thereof, and some other winter fun.] What

strikes me as a common problem that may contribute to this is the

difficulty of effectively insulating over the top plate of typical

roof/wall construction in vented-attic scenarios, invariably leading

to significant heat loss right above the eave where it’s most critical

to *not* warm the roof surface.

So the question is, failing a good way to deal with this area from

the attic side due to simple lack of room, would a more interior

approach help? Such as the attached image: a smallish unobtrusive

45-degree soffit of sorts, to connect the insulation from attic-floor

to wall and prevent the typical thermal bridge through the wood of

top plates and rafter connections. This could be done with or without

cutting the original drywall back, and taped and mudded and air-sealed

to become an integral part of the occupied box. It wouldn’t be

profoundly ugly or impractical; plenty of folks with upper-floor

kneewall setups live with angled parts of their ceilings.

_H*

GBA Detail Library

A collection of one thousand construction details organized by climate and house part

Replies

Hobbit,

Your idea was investigated in 2004-2005 by two researchers from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Jeffrey Gordon and William Rose. I reported on their findings in the October 2008 issue of Energy Design Update.

Here is what I wrote:

"...There are three reasons that the intersections of ceilings and exterior walls tend to be cold: insufficient insulation depth; the effect of cold air currents; and the geometry of interior corners, where the ratio of exterior surface area to interior surface area is greater than in the middle of a wall or ceiling.

"For the typical homeowner, the first sign of an attic insulation problem is ceiling mold near exterior walls. Gordon and Rose explain, “A common site of discoloration and mold growth, found usually in single-family homes with truss construction and low-slope roofs in heating climates, is the upper corner where the ceiling meets the outdoor wall. It is common in homes with high indoor humidity. It is unattractive, and it leads to complaints about mold in the home.”

"Gordon and Rose decided to investigate whether installing additional insulation at problematic ceiling/wall intersections would solve the moldy corner problem. Their research project was funded by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development.

"Working with other researchers at the Building Research Council, a University of Illinois research center, Gordon and Rose developed three ways to install additional insulation in problematic ceiling corners. They nicknamed the three methods the “insulation pack” approach, the “top-plate pillow” approach, and the “crown molding” approach.

The insulation pack approach requires workers to remove the home’s soffit. A piece of fiberglass batt insulation is then installed above the exterior wall’s top plate. The batt is held in place on the exterior side by a piece of 1-inch-thick rigid foam insulation, which acts as a wind block.

"The so-called top-plate pillow is a custom-made piece of semi-rigid foam. University of Illinois re-searchers worked with Foam Design, a foam manufacturer in Lexington, Kentucky, to develop a 22 1/2-inch-long L-shaped pillow of flexible 2-inch-thick white polypropylene foam insulation.

"After workers remove a home’s soffit, the pillow can be installed over the top plate of the exterior wall. The pillow is designed to stop short of the roof sheathing, in order to allow the free flow of air from the soffits to the attic.

"Unlike the other two insulation methods developed by the University of Illinois researchers, the crown molding retrofit is performed from the interior side of the problem area. Gordon and Rose ordered 6" x 6" expanded polystyrene (EPS) crown molding from Universal Foam, a manufacturer in Orlando, Florida (see photo below). The foam molding was manufactured with a fire-rated finish layer.

"Sections of EPS crown molding are easily adhered to gypsum drywall with urethane foam adhesive.

"To investigate whether additional insulation would lower the chance of mold development in cold ceiling corners, Gordon and Rose conducted a study at 18 single-family homes in a Chippewa community in Belcourt, North Dakota. The ranch-style homes were all owned by a public housing agency, the Turtle Mountain Housing Authority (TMHA).

"According to Gordon and Rose, the TMHA homes had “numerous cases of houses exhibiting mois-ture problems at the wall/ceiling juncture.” Each of the retrofit options (the insulation pack method, the top-plate pillow method, and the crown molding method) was installed on the north side of five houses. At three additional houses, all three retrofit methods were installed (each method in one room), except in a single untreated room that was left as a control.

"...All of the retrofit work was completed in early September 2004. From December 2004 through March 2005, the researchers monitored and collected data from a variety of equipment, including outdoor weather stations, indoor temperature and humidity data loggers, and thermocouple temperature sensors.

"The performance of the retrofit work was assessed by a variety of methods, including computer modeling, thermocouple data review, and infrared photo analysis. Gordon and Rose reached two major conclusions:

• Because of thermal bridging, the temperature of the ceiling directly under each roof truss is more critical than the temperature of the ceiling at the center of each framing bay.

• None of the three insulation retrofit measures made much of a difference.

"The roof trusses in the North Dakota houses created cold stripes on the ceilings. Gordon and Rose reported, “In addressing the moisture problem at the wall/ceiling juncture, the coldest and most critical temperature is at the truss. Retrofit insulation treatments cannot significantly change the temperature at the truss.”

"Elsewhere, Gordon and Rose explained, “All three treatments provided little to no improvement at the truss locations. There was some indication that the exterior treatments made a slight im-provement. The findings for the interior crown were more ambiguous. Ultimately, the thermal bridging that results in the temperature depression at the truss was not remediated by any of the insulation techniques.”

"Since the mold and moisture problems are mostly caused by thermal bridging through the truss framing, added insulation between the trusses is not a logical remedy. “We consider the insulation-retrofit idea to have been pursued fully in this study, with the finding that potential thermal improvements through insulation fail to significantly improve the thermal conditions at the truss,” wrote Gordon and Rose. “Retrofitting insulation is not likely to produce the desired benefits. A better strategy is to promote humidity control in affected houses.”

"Interviewed by phone, Rose readily admitted that their insulation strategies didn’t work. “These methods had so little effect that they aren’t worth considering,” Rose told EDU. The research find-ings sent Rose back to the drawing board, leading him to suggest a new remedy: wrapping the entire exterior (walls and roof) of the home with rigid foam.

"“Reducing the thermal bridge effect at a truss doesn’t lend itself very well to makeshift efforts,” Rose explained. “Any strategy that allows a truss member to be continuous from the inside to the outside means that the existing conditions can’t be substantially improved. To do it right, you have to cut off the overhangs, insulate the exterior of the wall and roof with rigid foam, and then reattach the overhangs.”

"Rose’s suggested remedy is similar to the “chainsaw retrofit” method pioneered by Rob Dumont in the 1980s."

.

Well, okay then! Nothing new under the sun. Although I was

thinking of something a bit larger, maybe a angled piece a

foot or more high without getting ridiculous. That might at

least make some of the thermal bridges longer, using a little

more of the wood's R-value... and of course with a generally

warmer attic from leakage, none of it would help anyway.

Of course right now everybody around here has an extra R-15 or

more up top, placing the roof deck much farther inward on the

thermal gradient anyway. Chase the "topside adventure" link in

the foregoing for more roof-romping and analysis... we're all

gonna have monster shoulders by March.

_H*