Hi there, first off let me say I am a “homeowner”, not a “builder”, so please excuse my lack of building experience.

Having had 3 major water issues in other houses in the past, I am “hydrophobic” (pun intended) and I am wanting to build a house that will not have moisture issues.

Let me explain what my wall plans are:

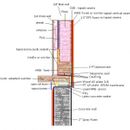

I am building a fairly straight forward house following the PGH (Pretty Good House guidelines). I live in New Brunswick Canada (Zone 7 – cold climate) and will be building a typical wall system found here (double-wall 2×4 (inside wall) and 2×6 (outside) with a poly membrane between them and outside sheathing covered by 1.5″EPS and WRB. It is this “2 vapour system” that has me worried and thus why I asking this question in the first place. The issue is my builder is not comfortable going more than 1.5″ of outside foam (For clarity sake, I have included a pic of my wall assembly (feel free to criticize ))

I can comment further on why I chose this wall assembly but this is not purpose of this post.

I have already seen on the website what the minimum amount of “outside foam” is recommended according to insulated wall values(as per Martin’s advice) (I know I am using too little) and he also stated that in some circumstances, here in the “cold country” at least, it would be OK and desirable to have both “Poly on the inside” and “foam on the outside” even if the foam is not of sufficient thickness.

My FIRST question is this: Is it OK to have a “hybrid” vapour barrier?

I have seen the many advantages of those “intelligent” vapour barriers (ie Intello) but am somewhat reluctant to spend all that money. Since air with vapour is denser than dry air, I would assume most moist air will fall towards the lower part of the wall cavity. Thus why not place an intelligent vapour barrier there (bottom 2′) and use “Poly” above it taping and sealing the joint between them? That way only about 20% of the wall would be “vapour permeable” and 80% “vapour blocked” Thus an 80% savings!

My SECOND question is:

Would not the inclusion of a desiccant (ie bentonite clay which is often used as a water stop and is available in Canada anyway – Website:

canadianclay.com/bentonite.htm ) in the wall cavities be a good idea? Especially in wall cavities under windows where leakage may occur? This clay will absorb 5-10 times it own weight in water and releases it slowly to prevent wood penetration of any leakage from absorbing into the wood (it can cycle like this many many times. Maybe a 1-inch roll place on the bottom plate? Granted I will lose some insulation value (not much as I am using Roxul which even if compressed retains it’s R-value), however, this would give the wall assembly time to absorb the water as water vapour as it is released by the bentonite. Seems like cheap insurance to me.

Thanks for taking the time to review all of this. Building a “new” house is such a humbling experience.

Paul

Replies

Your assembly should work with standard poly. As long as it is unfaced EPS on the exterior, this is still vapour permeable and will help with drying of your assembly.

In a well insulated and sealed house the temperature and dew point are the same along a wall height, there is no better spot for a smart vapor retarder. Your hybrid approach could work, but it would be way more work as now you are dealing with a horizontal seam in the middle of the wall. Pick one and use it all the way along the wall.

Bulk water leaks are best dealt with proper detailing. Well detailed window rough openings don't leak into walls. This is not hard to do.

There is no point for SPF on the inside of the basement. Just use standard EPS. You can adhere it to the foundation with glue and either strap it out for drywall or frame your basement wall in front of it.

P.S. If you are dense packing the service cavity, why not the whole wall?

P.S.S. I would inset your wall so the EPS is flush with the foundation bellow. You can now run the siding down without having to jog there.

Water vapor is a gas which mixes thoroughly in air, rather than sinking to the floor.

Bentonite absorbs water (lots of water) slowly and gives it up slowly, it's very low permeability (people use it to line ponds), and if exposed to bulk liquid water the surface particles will tend to dissolve and flow. I think this is a very novel use for it, and I doubt it will perform like you're hoping. Dense-packed borated cellulose insulation will absorb quite a large amount of water, if hygric buffering is the issue.

The "foam on the outside" rule tends to refer to simple stud walls, where the air barrier & vapor retarder is the sheathing on the outside of a single rank of studs (with cavity insulation between). This creates a problem where moist air free to slowly flow through the cavity insulation, contacts that cold sheathing and condenses/freezes there. Continuous exterior insulation helps prevent this by keeping the sheathing & studs warmer. I don't think this rule of thumb is going to apply directly to a double stud wall, which may not have the same issues depending on how it's configured.

Burninate,

Wouldn't a double-wall have colder sheathing, and be more susceptible to moisture accumulation? That seems to be what the testing shows. https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/article/is-cold-sheathing-in-double-wall-construction-at-risk

I would point you to this article from people who know more than me on the subject:

https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/article/exterior-rigid-foam-on-double-stud-walls-is-a-no-no

It sounds like the proposition of an interior vapor barrier and exterior foam/sheathing vapor retarder is not ideal.

---

I've gone back and forth on double stud wall assemblies, purely on paper. At present, the safest direction feels like giving in to a little thermal bridging in exchange for a mid-wall air barrier and better structural tie-in between inner and outer wall.

* Interior drywall

* Lattice of 1x3's or 2x4's for wire chase

* Intello Plus, possible laid over Insulweb if installers prefer

* Dense-packed cellulose between vertical load-bearing 2x4's or 2x6's, platform-framed

* 1st layer 1/2" plywood, taped

* 2nd layer 1/2" plywood, taped, offset seams

* Either dense-packed cellulose or rockwool between non-load-bearing 2x4's or 2x6's, balloon-framed

* 30# tar paper

* Lattice of 1x3's or 2x4's for vented rain screen

* Siding

This is a very thick, complex stack that tries to combine the advantages of things I've seen in a number of different places, and seems most economically feasible in a semi-panelized setup; Optimizing the sequencing & transition details is something I think about a little more than is healthy for somebody who isn't currently employed to do so.

Further to Burninate's comment about distribution of water vapor in air, the density of air with more moisture in it is lower than that of dry air. Water has a molecular weight of 18, while the average MW of dry air is 29, a mix of mainly nitrogen (MW 28) and oxygen (MW 32). Since a given number of molecules of any compound in the vapor state (at atmospheric pressure) occupy the same volume, regardless of what they are, displacing some heavier N2 and O2 molecules with water vapor lowers the air density. That's why low pressure areas are associated with humidity and rain.