Slab on Grade Foundation Option

LawrenceMartin

| Posted in Green Building Techniques on

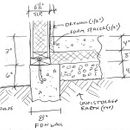

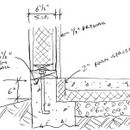

I am designing a small 630 SF house with a slab on grade project in a relatively dry Climate Zone 6 in the Mountains of Colorado. This house is designed using SIPs in lieu of standard framing and external insulation. I was originally planning to use a standard foundation/slab detail that I have seen many times at GBA and the BSC (Building Science Corporation) labeled as “Option B” in the enclosed sketch. I had three concerns about this detail.

1) The narrow 6 1/2” stem wall that is on top of the foundation looks weak and I see an opportunity for cracking at that inside corner.

2) This requires a finished flooring material to be on top of the concrete to hide the foam insulation at the perimeter. This is especially true where there is a door threshold.

3) There is thermal bridging at the base of the SIP where the sill plates do not have any external insulation.

“Option A” in the enclosed sketch, eliminates the short stem wall and extends the exterior wall to the top of the 8” foundation.

1) This eliminates any step at the top of the foundation.

2) There is a 1/2” foam strip around the edge of the slab to isolate the wood SIP from the concrete. that matches the thickness of the drywall hiding the foam strip.

3) The foam strip also isolates the non-treated SIP panel wood face from the concrete.

4) Thermal bridging is greatly reduced since the foam is the same depth as the sill plates.

I was wondering if anyone sees any problems with this detail that I may be missing.

Thank you in advance.

GBA Detail Library

A collection of one thousand construction details organized by climate and house part

Search and download construction details

Replies

Lawrence,

Someone posted a similar detail here s0me months back. I've never seen it used but it is intriguing. The only downsides I can think of are:

- The effect on wall height. That won't matter as much with SIPs as it would with conventional framing, where using pre-cut studs allows exactly the heights you want for drywall, etc.

- It brings the floor height up, meaning you don't get the benefit slabs on grade offer of facilitating no-threshold exterior entrances.

I'll be interested to see if someone comes up with a drawback we haven't thought of..

It looks like a good detail to me. I believe I've seen architect Steven Baczek share a similar detail. In addition to what Malcolm noted, I'd have some concern about the bottom of the framing being cold and damp, potentially leading to mold growth. But otherwise it looks fine.

For what it's worth, I use your "B" detail regularly, with stem walls reduced to as small as 4", and have never seen a failure. The IRC building code just says that the concrete wall needs to be at least as thick as the wall it's supporting.

Thank you, Gentlemen, for the response.

Malcolm, good points both. Although, the higher interior floor level might be nice if there is going to be a wood deck outside the main floor of the house.

Michael, I am interested in your concern about the mold. Is it that the thermal bridging was keeping that joint warm or all the exterior connection points at the sill plate that need to be protected from moisture? I was planning to have the exterior siding cover the foundation/sill plate interface by an inch. In which case, I should move the soil down an inch to match. I also will specify Conservation Technologies building sill gasket under the larger sill plate -- maybe both sill plates. I am also considering adding an appropriate tape that will cover the whole transition between the OSB SIP skin, sill plate, and foundation. I have to still research a product for that.

Building Sill Gasket Website: http://www.conservationtechnology.com/building_gaskets.html

Lawrence, a Therm analysis would be helpful, showing the temperature at each location in the assembly, but it looks to me like the upper mud sill (or lower wall plate) will be relatively cold--concrete is a good conductor of heat so you can assume if it's 10° outside, the innermost, uppermost corner of the concrete will also be close to 10°. The mud sill and sill above that will be closer to the indoor temperature but probably below 50°F for extended periods when it's cold outside, which is a temperature where condensation is likely to happen, depending on a few variables. Moisture, with temperatures above about 50°F, allows mold and fungus to flourish.

Michael, I think I see what you are referring to. I presumed that since the mudsill and upper sill are insulated by the SIP above, the dew point would be in the foam insulation of the SIP. On Option B, I can definitely see where the dew point would occur under that sill plate though. I wonder if this condition is also similar to a crawl space or basement assembly. In those cases, we usually encapsulate the inside with closed cell spray foam.

I'm having trouble seeing how the bottom of the SIPs or sill-plate has any more moisture risk than say a rim-joist and sill-plate insulated with foam on the inside as we do in conventional framing.

Malcolm, I don't love encapsulating rim joists with interior foam either, but at least they are usually thin and can dry easily to the exterior in most cases. You're probably right, though--I've just had enough bad experiences with SIPs that I'm cautious about any chances of moisture issues, as they are not easily fixed.

Micheal,

I take your p0int. SIPs worry me in the best of circumstances. I've been thinking about this detail for a while using framed walls, and that's where my mind was.

With seismic concerns out here I've become increasingly wary of framing small ledges, and have reverted to canting the outside of the stem-walls to reduce the thickness of the bearing surface. But I like the idea of not having to monkey with the top of the wall at all. Where I am I'd only need 1 1/2" of foam on top (under the slab). What I haven't done is run any of this by my structural engineer. I wonder how comfortable he would be having the slab above the stem-walls in a shake?

I think you are both starting to hit on an issue in building in Climate Zone 6. I specified the SIP panels for two reasons. 1) minimum external insulation would be very thick, and 2) I wanted to dry in the house as quickly as possible. On my last house in the Denver area, no one wanted to do the exterior foam. In a rural area where this house would go, I think it would be even harder. I haven’t found a solution that solves all the issues. Last week, I saw an article in JLC by Michael Anschel about using Huber Zip R12 and then a maximum of 2” of closed-cell foam in the cavities. But, that amount of insulation seemed to be too little to me (R12 c.i. + r13 cavity). In this detail, however, the ZIP R12 could overlap the foundation by an inch and protect the mudsill. But, then it creates the earlier problem that Malcolm brought up about standard stud lengths which sends me back to the more conventional Option B.

JLC Article: https://www.jlconline.com/how-to/exteriors/evolution-of-a-high-performance-wall_o

Lawrence, on a custom house I never worry too much about using standard stud lengths, as cutting longer studs to length is pretty quick. On production building it matters, but with high ceilings being popular now, 8' or 10' studs are at least as common as precuts (92 5/8" in the northeast, with other lengths common in some places) for custom homes.

Malcom's slab concerns are worth considering as well. In an earthquake the slab could shear off the wall framing.

I respect Michael Anschel but I don't see the point in spray foaming the stud bay if you're using Zip R-12 in climate zone 6. You'll be reasonably safe from moisture build-up in the walls with regular fluffy insulation in 2x6 walls with Zip R-12 on the exterior, for a nominal total of about R-32, or about R-27 including framing. A polyurethane SIP with a 5 1/2" core is about R-30 to R-33 (I'm sure they advertise higher values but that's for brand-new panels; as they age the R-value decreases.) You'll very likely find that SIPs are less expensive than conventional framing with Zip-R, but they probably won't last 100 years either.

Maybe I'm missing something, but with the wall being attached to the sill below the floor level by seven inches I'd think it would create a few problems for attaching the wall to the stem wall. I haven't built with SIPS so this might be a non issue, however if it was stick built then I'd think the walls would have to go up before the slab is poured? Building walls on a slab is nice as you have a good solid flat surface to work on.

Thank you, Andy. That is a great observation. In both of these cases, the exterior wall would be built on top of the foundation which is not always a flat smooth surface to be sure. However, that is usually where the sill plate is placed anyway when not using a slab on grade construction. This building has no internal bearing walls, so no need to worry about the internal framing walls either. If I use a monolithic slab, that would be a great way to place the framing on the smoother slab construction. But, I have concerns about the monolithic slab in our area.

But, you are correct, the exterior walls and roof would need to be built before the slab is poured. I would imagine that would be a bit more challenging than pouring a basement slab. At least with the basement slab, it is easy to get the pump hose in from above. In this case, it would need to be fed in through a door or window opening. From a sequencing point of view. Putting in the floor slab before the exterior walls might be an easier build.

Lawrence,

Here in the wet PNW we often pour the slab once the roof is on, or we might be waiting months. We use a line pump.

Is the SIP core polyurethane or polystyrene?

Either way, I would avoid Option A.

I was planning for polyurethane. Any thoughts on why you would avoid Option A?

Polyurethne is the better choice. Are you going with ThermoCore SIPS?

With Option A - The wall SIP panel will be sitting below the concrete slab, which is asking for trouble. When they pour that 4" slab, there really is no way to stop the concrete moisture from being absorbed into the OSB of the SIP. The foam board separating the 4" concrete slab and the SIP cannot stop moisture from seeping through. The OSB will wick up the moisture and the OSB will swell and turn into a mess, possible de-laminating at the bottom.

If you still choose Option A. You would have to run a plastic vapor barrier underneath the concrete slab and run the barrier UP above the concrete slab and tape the barrier ABOVE where the slab ends. Even then, it's still a bad idea in my view.

Peter,

If you wen't satisfied by using the poly (which will already be there under the slab) up the wall several inches to protect the SIPs, you could easily run a short strip of peel & stick membrane to0.

Malcolm,

True. I didn't see the call-out for the plastic barrier in the details. I agree, if Option A is chosen, one must run a water resistant barrier over the portion of the SIP that will be under the slab. Although I am still leery of what might happen to the 4"+ of OSB that is trapped under the concrete slab.

If that portion ever gets moisture ridden. It CANNOT dry out as wall SIPS (like roof SIPS) can only dry in ONE direction. With that SIP portion being under 4" of concrete and having a plastic barrier on it, the one path of drying is gone.

Peter,

I definitely have some misgivings about that too.

It looks smart to me. One consideration that nobody mentioned is the preparation of the soil--you need to remove all vegetation and a layer of top soil to get down to stable soil in either case. To then get to the scenario pictured, that might require lowering the grade nearby or adding more gravel than shown.

Good point, Charlie. Thank you for the reminder.