Eave insulation retrofit

All,

I am in the process of renovating a 1940s farmhouse in Westfield, MA and I am running into a bit of a tricky situation regarding existing eaves.

The house currently has the same level of 1-2″ rock wool insulation in the walls and ceiling that is poorly applied and providing a very minimal amount of real-world insulation. As for the attic space, there are no soffit or ridge vents and currently only 2 working gable vents. I was originally planning to leave the walls and ceilings in their current state but after uncovering the situation I have decided to begin the process of moving towards The Pretty Good House.

My question today is this:

How do I expose the original attic floor boards to the living space below, as I would like to highlight the history of this farmhouse, while upgrading the thermal performance of the walls, eaves and ceiling?

My current theory is to install 3.5″ rock wool insulation in the existing stud bays with 2″ of rigid insulation to be applied to the exterior when I replace the existing siding in the next year or so. For the attic I plan to install an air barrier on top of the attic floor with rigid insulation on the underside of the rafters to create wind-wash-free space for 18″ of blown-in cellulose insulation.

The issue then becomes connecting the exterior walls to the new attic insulation in a way that meets all the typical requirements (attic ventilation, air-tightness, insulation, and etc). I would like to avoid using rigid/spray foam but understand where it may be required.

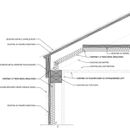

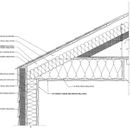

See attached for existing eave and my current iteration of proposed detailing. Current issues are the minimal insulation at the lowest point of the roof (add rigid insulation soffit to the interior?) and lack of venting. The existing construction is leaky enough for this to be okay, but is the future construction too air-tight to get away with this?

Thanks!

GBA Detail Library

A collection of one thousand construction details organized by climate and house part

Replies

There are no interior side air barriers specified in either of those details, which is a problem when using air-permeable fiber insulation in the cavities. Without an air barrier you will have orders of magnitude more moisture transport to the cold sheathing than you do with the current painted plaster & lath.

In a vented attic you don't need to use the foam board at all any air barrier will do. Installing half inch OSB above the plank flooring and taping/sealing the seams as the primary air barrier is good enough, as long as you maintain your soffit-to-ridge venting.

Your eave detail still tapers to a thin spot at the edges. If instead a flat stepped ceiling you angled the ceiling parallel to the rafters you could still maintain a continuous R54 cellulose using fiberboard or OSB as the exterior side air barrier for the insulation at that point, and half-inch OSB as the interior side air barrier under your t & g interior paneling.

You may want to use taped/sealed OSB as the interior air barrier on the walls since it's also a "smart" vapor retarder- it will block interior moisture diffusion drives in winter without dramatically reducing it's drying rate toward the interior the other 8-9 months out of the year.

Matthew,

Dana gave you good advice. You definitely want to install a tight air barrier above the attic floorboards before installing insulation.

The best way to address the "thin insulation at the eaves" problem is to install one or more layers of rigid foam above the roof sheathing, followed by a new layer of OSB or plywood and new roofing. This approach isn't cheap, but it's the best way to go. Here is more information: How to Install Rigid Foam On Top of Roof Sheathing.

If you're stuck with having to insulate the thin area near the eaves from below, because you can't afford to install rigid foam above the roof sheathing, you should consider using closed-cell spray foam in this area -- as least as far back as you need to go until there is enough room for about R-38 of cellulose.

Thank you for the responses.

Dana,

I am planning on installing an air barrier between the cellulose insulation and the attic floor but have not decided on the method. OSB will be problematic due to the size, accessibility and layout of the attic. I was thinking of using Membrain by Certainteed taped at all seams to perform this task. Also, the existing attic does not have soffit or ridge vents at the moment.

As for the interior side air barrier, it is my understanding that 2" of exterior rigid insulation with taped seams will sufficiently warm the exterior sheathing above the dew point and prevents drying to the exterior. Considering the dry winter air will the sheathing not be fine until the vapor drive reverses in the spring and it is able to freely dry to the interior? If not, can I install Membrain behind the tongue and groove in this instance as well? I would prefer to avoid the increased thickness of an OSB or gypsum backerboard if possible.

Noted regarding the foam board in a vented attic. My thought is that it would be easier to install a continuous mitered rigid insulation board with taped seams to the face of the rafters to act as both a rigid air-tight baffle for the cellulose and to secure the air barrier in place on the floor with a caulked joint.

I agree that an angled ceiling would be the most efficient method of insulating the eave in terms of volume but I believe it would be more complicated than it's worth. I will look into utilizing an insulating soffit that will also provide an additional thermal break for the top plate.

Martin,

Rigid insulation on the roof is definitely not in the picture at this time due to budget constraints. I am also against the use of spray foam as a permanent solution to what I believe to be a temporary problem (a discussion for a different time).

I am interested in understanding more about vapor drive in the winter in this climate zone.

Is it truly necessary to provide an interior air barrier if you control the humidity within the space? IE. negative whole-house ventilation through bathrooms, proper exhaustion of kitchen moisture and/or a dehumidifier?

Is this situation better without exterior rigid insulation so the sheathing is cold (no rot) while it is unable to dry to the exterior (exterior vapor barrier) but is able to freely dry to the interior when the weather warms and reverses the vapor drive?

Matthew,

Q. "Is it truly necessary to provide an interior air barrier if you control the humidity within the space?"

A. If you are insulating with an air-permeable insulation like mineral wool or cellulose, an interior air barrier is always desirable. The interior air barrier reduces exfiltration -- thereby reducing moisture flow from the warm, humid interior to the cold sheathing -- and reduces the chance of convective loops that increase heat flow through the insulated assembly.

There is no downside to air sealing efforts. To the best of your ability, create an airtight layer on the interior side of your insulation.

Q. "Is this situation better without exterior rigid insulation so the sheathing is cold (no rot) while it is unable to dry to the exterior (exterior vapor barrier) but is able to freely dry to the interior when the weather warms and reverses the vapor drive?"

A. Your question is hard to decipher. Certainly, warm sheathing is always better than cold sheathing, because warm sheathing is less likely to accumulate moisture during the winter than cold sheathing.

Certainly, in your climate, an exterior vapor barrier is always a bad idea, unless the vapor barrier has a high enough R-value to keep the sheathing above the dew point during the winter. In general, if you expect your wall sheathing to get damp during the winter -- as happens with most cold-climate walls that lack exterior rigid foam -- then you need to provide a drying path the the exterior, not the interior, for the damp sheathing.