If you’ve ever seen frost in the attic in winter, it’s pretty to easy to understand why it’s happening. It’s the same thing that causes morning dew on the grass, frost on the exposed half of my car, or water dripping from the bottom of a duct. Condensation requires two things: water vapor in the air and a surface cold enough to entice that water vapor to leave the air.

Look at the nails in the lead photo above or the metal ridge vent below. Those nonporous materials will collect water from the air when they drop below the dew point temperature of the water vapor in the air. Let’s apply these principles to the frosty attic in the first two photos.

The symptom: moisture in the attic

When it gets cold outdoors, an unconditioned attic gets cold. The roof deck gets cold. The framing gets cold. Everything in the attic gets cold. But cold air is dry air, so if the attic is filled with outdoor air, there shouldn’t be a problem.

Clearly, though, this house in central Illinois had a problem, as evidenced by all the frost in the attic. The lead photo above shows frost on the roofing nails and on the plywood roof deck. The second photo shows frost on the underside of the ridge vent. Those materials had to be at temperatures below the dew point for this to happen. But where is the moisture coming from?

The third photo above gives us the answer. Someone laid down a sheet of plastic in part of this attic. You can see condensation on the underside of that plastic. Aha! The moisture is coming out of the insulation! Uh . . . well . . . not really. The moisture is coming from below the plastic, but the real source of water vapor is the indoor air in the living space below the attic.

A related symptom occurs in some frosty, wet attics. If the roof deck and framing stay wet long enough, mold can start growing there. In many homes, frost in the attic might lead to high heating bills and perhaps reduced material durability. But if you get a serious microbial infestation, your health could suffer, too.

The cause: air leakage

Many attics have a lot of air leakage, especially in homes built more than ten years ago. In winter, the indoor air will have more humidity than outdoor air. If it leaks into the attic, that raises the dew point temperature of the attic air. And that makes it more likely that water vapor in the attic air will find cold surfaces, creating the kind of condensation and frost you see above.

Houses have A LOT of pathways that let indoor air leak into the attic. The photo above shows an open chase on the right and an unsealed penetration on the left. There are also unsealed wiring penetrations, an unsealed gap on both sides of the top plates, dropped soffits, can lights, and more. And sometimes contractors get really creative with their holes.

The photo above is one of my favorite air leaks. This was in the kitchen of my wife’s parents’ house. As I crawled through the attic, I found an extremely dirty patch of insulation. I pulled it back and looked down through that hole. After a minute of being puzzled, I realized I was looking at the back of the refrigerator. When they had their kitchen redone a decade earlier, the contractor must have thought it would be a good idea to vent the fridge to the attic. Of course, that extra heat from the fridge accelerated the stack effect, sucking a lot of their heated air up into the attic each winter.

By the way, some people believe that houses should be intentionally leaky. You know, a house needs to breathe, right? Wrong!

The solution, part 1: air-sealing

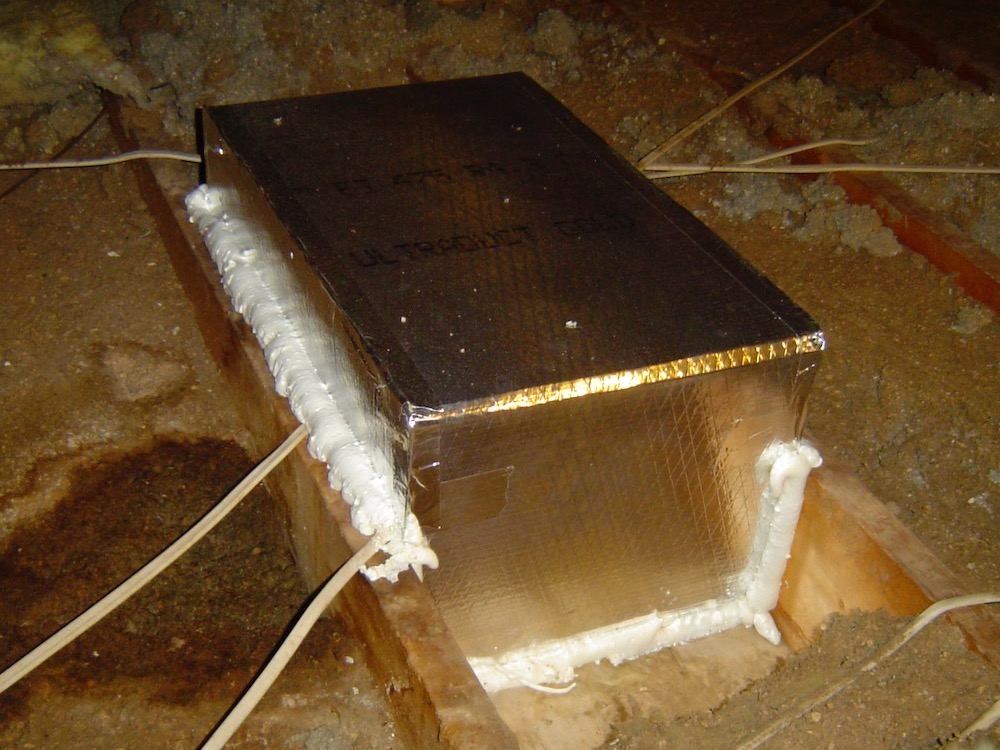

So, the first thing to do is keep the water vapor out of the attic. You want to keep it in your living space anyway because leaky houses tend to be too dry. So get all the holes in the attic floor sealed up. The photo below shows how I sealed a recessed can light with rigid fiberglass and spray foam. You can buy covers that make this job a lot easier.

The gap between each side of the top plate and the ceiling drywall also can leak a lot of air. The gap may be small, but it runs for hundreds of feet throughout the attic. The photo below shows that gap sealed with spray foam along with a sealed wiring penetration.

There’s a lot of really good information available for attic air-sealing. Here’s a really nice attic air-sealing guide from Building Science Corporation. (Scroll down the page and you’ll find the full pdf download link on the bottom right.) Another really good resource is the Air Sealing and Insulation Key Points document (pdf) that Southface created for the Georgia energy code.

The solution, part 2: venting the attic with outdoor air

Another way to reduce the likelihood of getting frost in the attic is to vent the attic with outdoor air. Cold air is dry air, so bringing outdoor air in reduces the humidity. That in turn reduces the dew point temperature, making condensation and frost in the attic less likely.

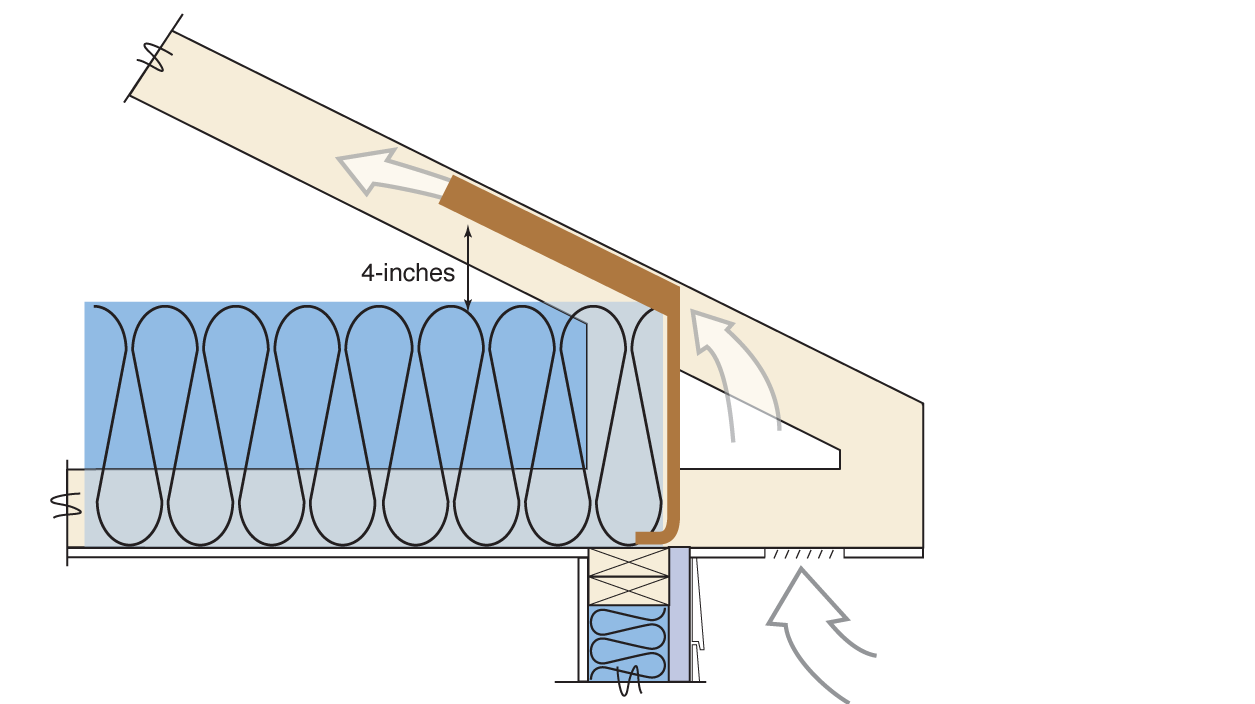

The diagram above is from Southface’s key points document. It shows three essential features of good attic ventilation through soffit vents. First, you need to keep the outdoor air from blowing through the insulation. Second, you need to channel the air above the insulation. Third, you need that to end high enough above the insulation that it won’t get clogged with insulation.

You accomplish all three of those things with a good ventilation baffle, shown in brown above. They’re usually made of cardboard or foam and get stapled in place before insulating. If you’ve already got insulation, you’ll have a lot of fun squeezing into that tight spot to install them. (And by fun I mean torture.)

The photo above shows properly installed ventilation baffles in a home being built. The ventilation channels, of course, must be coupled with soffit vents and ridge vents to allow air to move. When it’s working well, the attic can stay dry enough to prevent condensation and frost. The home pictured at the beginning of the article had a ridge vent and soffit vents, but the insulation blocked the openings near the soffits, so it didn’t get a lot of outdoor air.

The solution, part 3: encapsulating the attic

Another way to solve the problem of frost in the attic is to encapsulate the attic and turn it into conditioned space. That’s what I’ve got in my house, and it works great. It’s especially helpful if you have any HVAC equipment or ducts in the attic.

By encapsulating the attic, the air in that space will be close to indoor conditions of temperature and humidity, but there won’t be any cold surfaces for water vapor to condense on. You can insulate the roof deck with spray foam insulation on the underside, rigid insulation on top, or a hybrid insulation system.

Buffer spaces like unconditioned attics, crawl spaces, and garages can create a lot of problems in homes. So does the crazy idea that a house needs to breathe. By applying well-known building science principles, we can have eliminate frost in the attic. We can have a more comfortable house. We can have better indoor air quality.

What symptoms do you see in your house?

_______________________________________________________________________

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He also has written a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard. Photos courtesy of author, except where noted.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

3 Comments

With raised heel trusses I extend the wall sheathing to within 2" of the roof sheathing. Then my air chutes go in place. This makes for a more robust and airtight wind wash barrier, the wall sheathing also helps tie the rafters in.

Oh god - I got this phone call from a client, saying exactly that - it was snowing in their attic. I'd hired an insulation contractor to lay blown in their attic, and they didn't bother doing any air sealing. Same amount of moisture as before, much less heat flow to keep the sheathing above dew point.

Fortunately hiring a competent insulation sub for a half day solved the problem. An early lesson learned.

This article is the best explanation I have found, including solutions, for attic condensation on the web. Most related articles or videos briefly mention that attic condensation (leading to frost in winter and then dripping water or “rain” as the frost melts) is due to moisture or humidity getting into your attic - but never mentioning the correct reason why this occurs and the solution for it. If any solution is offered, those articles and videos will often incorrectly state that the problems are due to inadequate insulation.

In fact, the solution is all about having an air-tight membrane preventing humid air from entering the attic in the first place.

Case in point: My 35-year-old house is located in Calgary, AB, Canada. Canadian winters are cold but Calgary winters are also punctuated by chinooks, which are periods of several days of strong, warm, westerly winds that rapidly increase air temperature. When this happens, any frost that has formed in your attic due to leakage past the vapor barrier (membrane) will rapidly melt, causing "attic rain". This "rain" is very destructive: in extreme cases causing stained ceilings, ruined insulation, black mold...all very nasty and expensive.

So, before you re-insulate or add additional insulation to your attic, make sure you have sealed ALL of the leaks such as gaps, holes, rips and tears in your vapor barrier BEFORE you spend time and money on insulation. Without doing so, you will be wasting your money and effort.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in