Where to put the air barrier in an assembly may seem obvious, but this question has many dimensions . . . literally. Let’s look at the question of air barrier location from three perspectives. First, building assemblies are three-dimensional. The air barrier can go on the inside, outside, or in between. Second, the type and location of insulation makes a difference. Third, the air barrier can include or exclude buffer spaces, like a crawlspace or attic. Which way should you go?

Inside, outside, or in-between

Most houses in North America are built with framing lumber that creates frames for the floors, walls, and ceilings. The building assemblies aren’t solid pieces of a single material, as a concrete wall is, but have an outside, an inside, and interstitial spaces in between.

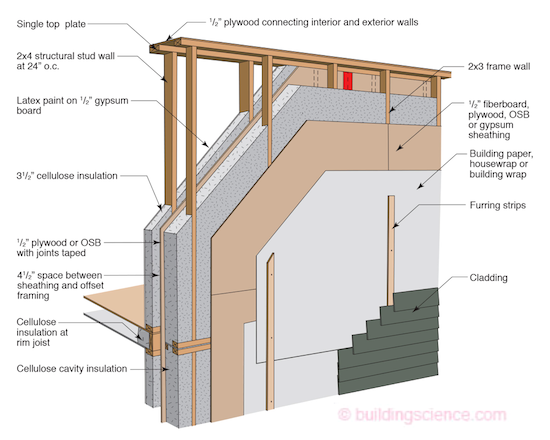

The outer surface has sheathing, control layers, and cladding. The inside has the inner surface, with drywall, and perhaps a vapor retarder. The in-between part has wood framing and insulation-filled cavities. This kind of structure creates interstitial spaces that air leaking through the enclosure has to pass through to enter or leave the house. Double-stud walls have even more complex structures with the possibility of another layer between the two sets of studs. (See end of next section.)

“Buildings are complex three-dimensional airflow networks driven by complex air pressure relationships.” —Joe Lstiburek

These three-dimensional building assemblies mean that air can leak in at one location, travel through the interstitial spaces, and come out somewhere entirely different. During a blower-door test, for example, you can feel air coming in through switches and outlets even when they’re on interior walls.

The interstitial space the air traveled through to get to the switch or outlet was the empty wall cavity. The place where the air came in might have been a wiring penetration at the top of the wall. That unconditioned attic air then travels several feet before entering the living space.

Think about the complexity of the structure of a framed house. A hole in one part allows air to get in. That air can move through a floor, wall, or ceiling, looking for a hole or crack that lets it get into the house. The distance could be a few centimeters, or it could be 10 meters (33 feet). The air keeps going, though, pulled by a pressure difference. It’s like ants getting into a house through the basement, traveling through interstitial spaces, and coming out in the kitchen, drawn by the crumbs they find there.

Outside is usually best

Now that you understand this kind of air leakage, you probably can guess the best place to put the air barrier for most buildings. It’s on the outside of the structure. Keep all unconditioned air out of the interstitial spaces. That solves most problems associated with air leakage. (The one that it doesn’t solve is moist, indoor air getting into wall cavities and condensing on the back side of cold, exterior sheathing. For that, the best solution is exterior insulation. Barring that, an interior air barrier and maybe a vapor retarder will do the job.)

Interior air barriers used to be a thing. Building scientist Joe Lstiburek even wrote a book on the airtight-drywall approach in the mid-1980s. Air barriers on the interior side of the structure certainly can keep unconditioned air out of the house, but they’re not ideal.

One big drawback with interior air barriers is the potential for moisture and mold on the backside of drywall in humid climates. In an air-conditioned house, the drywall will be cool in summer. Without an exterior air barrier, humid, outdoor air can get into a wall cavity, find that cool drywall, and get the drywall wet enough to damage it or grow mold.

Another problem with interior air barriers is that they’re not tamper-proof. When someone makes extra holes trying to hang a picture or doesn’t seal the gap around the new thermostat, they’ve compromised the air barrier. When it’s a choice between the inside and outside of the structure, the outside is the better choice for the location of the air barrier.

But there’s another option, too. Some superinsulated walls—like Lstiburek’s ideal double-stud wall shown above—are really thick. Often, the air barrier goes somewhere in the middle of such a wall. That’s a really good place to put the air barrier because it’s protected from damage from both sides.

Where’s the insulation?

The second perspective of air barrier location has to do with its relation to the thermal control layer (i.e., insulation). For insulation to do its job of limiting the flow of heat, it needs to be free of air flow. The most commonly used insulation in homes is fiberglass, which is air permeable. When air flows through fiberglass or any other air-permeable insulation, it loses some of its ability to resist heat flow.

The implication here is that the air barrier needs to be right next to the insulation. You can’t have an effective building enclosure, for example, if you put fiberglass batts in a stud wall with no air barrier, as shown above. The same is true when your air barrier is at the subfloor over a vented crawlspace, and the insulation is on foundation walls that also contain vents allowing the free movement of air between outdoors and the crawlspace. The air barrier needs to be aligned with the insulation. Air-impermeable insulation materials have this alignment built in because the insulation is also the air barrier.

What about buffer spaces?

The third perspective of this question is the decision about whether buffer spaces should be included or excluded. The air barrier, recall, needs to be at the boundary between conditioned and unconditioned space. In complex buildings, it’s sometimes difficult to see exactly where that boundary is . . . or should be. We know, for indoor air quality reasons, a house needs a robust air barrier separating a garage from the living space. Basements, however, are often included, and that’s generally the best choice because of how difficult it is to isolate the basement from the living space above it.

To find the best place to put the air barrier with buffer spaces, you need to evaluate the pros and cons of each choice. How will including or excluding the buffer space indoor air quality? How easy will it be to do the air sealing? Which will be easier to insulate? Crawl spaces and basements are usually better kept inside the building enclosure. Attics can go either way, although it’s easier and less expensive to put the air barrier at the attic floor.

In the end, you want a house to have the best possible air barrier it can have. It should be protected from damage, aligned with the insulation, and exclude buffer spaces you don’t want inside the building enclosure. And then you do a blower door test to find out how airtight the house is.

_________________________________________________________________________

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard. He has a PhD in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

8 Comments

Which location is easiest to seal against penetrations made after the house is otherwise complete? For interior/exterior I suppose it depends on the finishes/cladding, but wouldn't the middle be difficult (or at least, invasive) no matter what?

Is there a reason to not have two air barriers: one on the inside that retards vapor and an airtight exterior WRB?

I was talking with the owner of a well-respected local sheetrock company years ago, reviewing details of an addition we were building, in coastal Maine. We were discussing insulation, and he shared some advice, which went something like this: "Make sure you only have one air barrier. I've been working in this business for almost 50 years, and torn into a lot of walls. If you've got two air barriers, you're going to have moisture problems. The insulation needs a way to dry out. You wouldn't believe some of the stuff I've seen growing inside people's walls. "

Doug,

Unfortunately he had it all wrong. Air-barriers don't impede drying or cause moisture problems, vapour-barriers do. He probably just didn't understand the distinction between the two. Having two layers detailed as air-barriers, while not necessary, does make for more resilient building assemblies.

Sorry, I think we were probably talking about vapor barriers - we were discussing the paper-faced fiberglass in combination with foil-faced polyiso boards, and how that would create two vapor barriers.

Doug,

In the very rudimentary building science classes I took in architecture school during the 1980s there was no understanding of the difference between the two, and to be honest it wasn't until I started frequenting GBA about a decade and a half ago that I began to see the distinction between their two functions, so it's not surprising that another old guy like me might have got his wires crossed a bit.

:)

How should an air barrier connect to a vented attic?

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in