This story is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.

Summer temperatures in Chicago normally peak in the low 80s, but in mid-July 1995 they topped 100°F with excessive humidity for three days straight. Emergency rooms were overwhelmed with cases of heat exhaustion and heat stroke, especially in urban, low-income, and minority communities. By the time the heat wave receded, more than 700 people had died.

The Chicago heat wave spurred some cities to start providing free air conditioning for at-risk populations. But in my lab at the University at Buffalo School of Architecture and Planning, which focuses on reducing climate change impacts on cities and buildings, we have found that air conditioning and other fossil fuel cooling systems can create long-term risks even as they solve short-term problems. As climate change makes heat waves more frequent across the region and the nation, cities will need more tools to protect their residents.

In the years following Chicago’s 1995 extreme heat event, researchers tried to understand what had caused so many excessive illnesses and deaths. Some experts argued that Chicago’s 700 deaths were a symptom of ongoing neglect and isolation of vulnerable residents in American cities. Others took an epidemiological approach, focusing on preexisting health conditions and demographic factors such as advanced age.

Many studies agreed that access to air conditioning had helped to protect people from temperature-related illness and death. In response, some municipalities began to provide free air conditioning systems to high-risk populations. This step helped lower-income residents, although many struggled to pay the higher electricity bills associated with keeping a house cool.

But there’s a larger conundrum: Air conditioning cools people during heat waves, but wherever fossil fuels provide electricity, running air conditioners contributes to global warming. Cooling systems also strain the electrical grid, potentially causing brownouts and blackouts during periods of high demand.

Great Lakes residents at risk

In the Great Lakes region, climate change models anticipate that global warming will increase the risk, intensity and duration of temperature extremes. This forecast presents a challenge for cities like Rochester, New York, which typically only experience about 12 days over 90°F in the summer. By the end of the century, over 70 days in summer could be in that temperature range.

In addition, cities including Detroit, Toledo, Cleveland, and Buffalo have aging populations and high rates of poverty. Both of these factors increase vulnerability.

Before the advent of air conditioning, passive cooling systems were the norm in building design. Window shades, light-colored materials and coatings, insulation and natural ventilation all reduce temperatures indoors. Recently, researchers have renewed their interest in “passive survivability,” or systems that don’t require electricity but still protect people during a brownout or blackout.

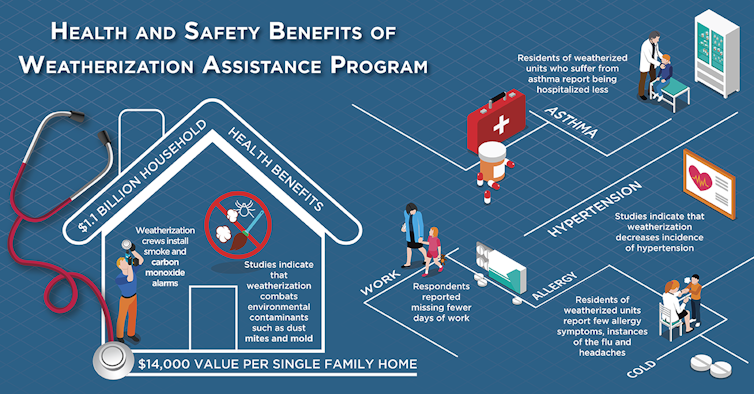

Passive systems are easily incorporated by architects into the design of new buildings, but existing houses need retrofits. Since the 1970s, the federally funded Weatherization Assistance Program has provided billions of dollars to help low-income households protect themselves from winter weather and save money by making their homes more energy efficient.

Unfortunately, these programs typically do not invest in cooling strategies in cold-climate cities because these measures don’t meet their cost effectiveness tests. This represents a missed opportunity to protect residents from summertime heat waves.

Making homes safer through weatherization

As the COVID-19 pandemic has shown, access to safe housing is a critical resource. A national evaluation of the Weatherization Assistance Program indicates that weatherized homes may be better equipped to provide safe, healthy environments in times of need.

For example, programs like the “Warm and Dry” effort from People United for Sustainable Housing in Buffalo provide basic repairs that can stop the growth of mold indoors. Other weatherization providers give advice on cleaning and maintenance that can reduce the number of asthma attacks.

Unfortunately, due to funding constraints, weatherization programs can’t ensure necessary repairs in every household that qualifies. And taking on simple home repairs can be surprisingly difficult, especially for households with limited financial resources.

For example, opening windows is critical in heat waves, but in many older homes windows may have been painted over several times. In cities like Buffalo, which has one of the oldest housing stocks in the country, cracking a window may require several steps.

Once windows are freed, damaged locks or balancing mechanisms often need to be repaired. Screens should be installed, since open windows can allow insects or other pests into the house. And any lead paint on windows needs to be removed safely. Old windows contain high concentrations of lead-based paints and coatings and can contribute to lead poisoning.

Given the challenge of weatherizing a home, I believe that federal and state governments should begin to examine ways in which weatherization can help prepare our communities to shelter in place in the future from heat waves, extreme precipitation and other forms of climate weirding.

A weatherization stimulus

In 2009 Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in response to the ongoing financial crisis. The law authorized a one-time $5 billion increase in weatherization funding.

A Department of Energy analysis shows that this program saved households an average of $3,190, reduced carbon dioxide emissions by over 7.3 million metric tons and created 28,000 jobs. In 2019, the agency reported that every dollar invested in weatherization returned $1.72 in energy savings and $2.78 in other benefits to the economy.

Congress has already passed a $2 trillion federal stimulus package to help the U.S. economy recover from the coronavirus pandemic, and more rescue packages are expected, possibly including infrastructure investments. In my view, expanding the Weatherization Assistance Program could put unemployed people back to work, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and help our cities prepare for an uncertain climate future.

–Nicholas Rajkovich is an assistant professor of architecture at the University at Buffalo, The State University of New York. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

7 Comments

"Summer temperatures in Chicago normally peak in the low 80s"

God, I WISH Chicago summer temps. usually peak in the low 80s! More like mid 90s+ with terrible humidity.

If the Great Lakes have higher temps, over a longer period of time, we might tip the winter/not winter ratio past 40% of the good weather soon. In Northern Wisconsin we haven't been getting consistent warm days and nights until mid June and it ends in September. I would love some more heat here. I am doing my part for making my home more efficient, by the way, no matter what.

Great commentary. New homes are such a small percentage of where we live, every year less and less. Creating livable space and resilient structures within the existing stock is most important. Thank you for your commentary Nicholas, I have shared it with several.

The savings mentioned by the author get even greater when including factors like wellness, reductions in chronic conditions like asthma, sick days from work, etc.. As a result, the weatherization program pays for itself several times. In addition, it trains and employs thousands of people around the country, has bipartisan support, and receives a pittance of funding compared with other government programs. Unfortunately, it’s still ‘under the radar’ . . . the private sector still hasn’t fully embraced weatherization, partly because it’s invisible and doesn’t have the sex appeal of granite countertops. And low-income people realize the monetary benefits quicker. However, our choices will become more Faustian if we continue to avoid reality . . . put another way, climate change is making all of us equal.

The greenest building is the one already built. Old windows with lead paint can be restored safely without needing replacement windows. Field studies (not laboratory studies funded by window replacement companies) proved that restored and weatherized windows can be equal or more energy efficient as replacement windows. Old lead paint can safely be removed. Infrared paint removers such as Speedheaters (www.eco-strip.com) can heat lead paint at low temperatures which don't release lead fumes yet create soft paint for easy scraping and safe containment. Contractors do not need to be hired; homeowners can do the restoration themselves. By weatherizing the window and even adding storm windows, further sealing can be done. The goal is to make the old windows operate in the summer as they were originally designed: lower the top pane to let hot air escape and raise the bottom pane to let cooler air come in. In winter, the good sealing of the restored windows and storm windows make them energy efficient. We need to encourage old home owners to use the most sustainable materials for restoration - existing building structure such as: windows, doors, transoms, etc.

Catherine,

Before any homeowners take your advice to strip lead paint from their windows themselves, they should take a course on lead safe practices-- especially if there are children in the house or women of child-bearing age. Attempting to remove lead paint is potentially hazardous to the health of do-it-yourself homeowners, their children, and other members of their household. Among the possible effects of this type of work are permanent brain damage of any children in the house.

For more information, see "What Should I Do With My Old Windows?"

Martin,

Excellent article above and all the comments. For sure, most of the issues of lead paint safety and restoration of windows were covered. I usually harp on lead safe work practices when I write or talk about restoration of any wood surface. On this May 12th article comment, I was restraining myself to stay on topic. One disagreement I have with you. Even after becoming RRP certified trainer myself, I believe homeowners can do the work safely with safe tools like the Speedheaters, PPE and safety materials in their work areas. Expensive contractors with lots of overhead are not needed. The EPA materials and internet resources are excellent. My position is that homeowners are going to strip their homes anyway, and the ones that are lower income will be doing it themselves. Given their budgets, I would rather have them use lead safe tools and methods and keep those old windows for decades more rather than buying the disposable ones which must be replaced again in 15-20 years. Our replacement windows (which we bought before I joined the restoration industry) failed in less than 10 years. I appreciate you reminding me and your readers about lead safety. Carry on!!!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in