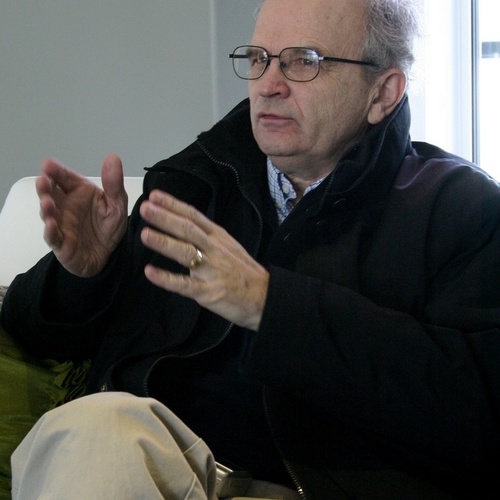

Image Credit: Steven Bluestone

Steve Bluestone, the New York real estate developer with a special interest in a building material that most builders ignore, is about to embark on a self-financed experiment that will test the effectiveness of high-mass walls in a cold climate.

Bluestone last year built a house in Hillsdale, New York, with autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC). The blocks, produced by a single manufacturer in the U.S., are lighter than conventional concrete blocks and better thermal insulators. A few high-performance builders use them, but most do not. Bluenose thought they deserved a try.

Exterior walls of the 4,200-square-foot house are built with 8-inch-thick AAC block wrapped on the outside with 4 1/2 inches of rigid polyiso insulation and finished with James Hardie fiber-cement siding. He learned recently that the building, described earlier this year in an article at GBA, will be certified by the Passive House Institute U.S. As far as Bluestone knows, it will be the first AAC building in North America to be certified.

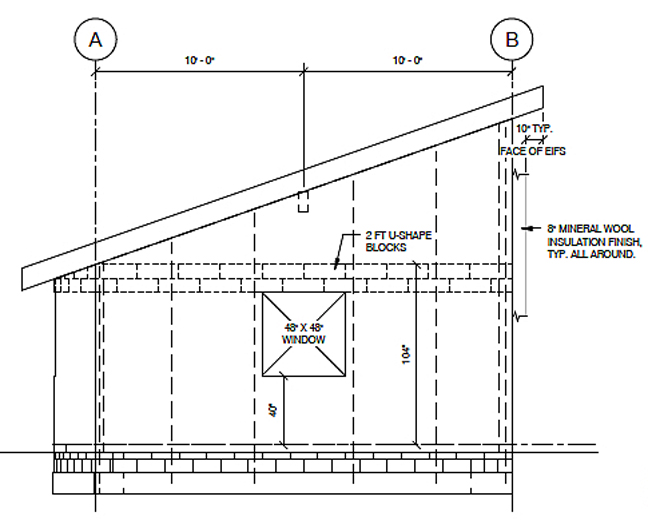

Now he’s drawn up plans for a woodworking shop on the property that will help him learn more about AAC construction: whether there are less expensive ways to use it (he acknowledges the house was expensive), and whether Passive House computer modeling of high-mass walls is accurate.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

“I’m still not done figuring out this AAC, and seeing what it can do, and how to do it cheaper, and I thought: Why not build a shop with AAC and try something without this outboard polyiso-Hardie board-expensive system?”

Insulating in stages

Instead of insulating walls with polyiso, Bluestone plans on using Roxul mineral wool, attaching it directly to the outside of the block and finishing it with stucco. That should lower labor costs. But the exterior insulation won’t go up right away. Bluestone plans on adding it incrementally, taking two or three years to find out just how much exterior insulation is needed before the building meets energy requirements of the PHIUS building standard.

While Bluestone’s exterior walls will be subject to change, the structural insulated panel (SIP) roof, the windows, and the sub-slab insulation will be designed to meet Passive House requirements from the start. By adding wall insulation in stages, and measuring energy consumption at each step, Bluestone in effect will be testing the accuracy of the computer software (PHPP) that designers use to predict energy use in Passive House buildings.

Bluestone explained it this way: “I’ll put the heat pump in and let it run for a year and see how poorly it did, because it’s only an R-10 with a mass wall. Then, in year two, put some insulation on the outside, incrementally add it, go a second year, a third year, until I get to the Passive House level.

“The Passive House program might say 10 inches of Roxul,” he continued, “but I’ll have this mass wall thing and this unknown – of the effect of a mass wall. What happens if I do this every year, and I go in 4-inch increments – zero inches the first year and here’s my energy bill to heat the place, 68 degrees all year long…Year two, put 4 inches of Roxul on the outside and find a way to shed water temporarily, then monitor for another year. Do the math after the year’s up, go to year three and put another 4 inches of Roxul on.

“Now I have 8 inches of Roxul and 8 inches of block, and lo and behold, maybe that’s enough,” he said. “I want to see if the program is right by working up to its number and if I reach Passive House consumption on a watts-per-square-foot basis before I actually that much insulation that Passive House said to put on, well, that would be an interesting story.”

Testing lab results

Thick walls made from heavy, dense materials — such as adobe in traditional houses in the southwestern U.S. — can, under certain weather conditions, soak up heat during the day and release it at night. This keeps people comfortable by protecting them from the sun’s heat during the day, and warming them at night after the sun has gone down. By the time the walls have lost all their heat overnight, the sun is rising to warm them up again.

High-mass walls were a cornerstone of early passive solar design. But in a cold climate, where daytime temperatures never get very high during the winter, the walls get cold and stay cold for months on end. They can be a liability, not an advantage.

The performance of high-mass walls has been studied by building scientists, including researchers at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory, but Bluestone says there’s a shortage of the kind of empirical evidence his experiment should produce. And it may help deflate some of the claims builders have made over the years.

“There’s a whole bunch of people I deal with in the concrete world and many of them say, ‘Oh, the mass wall. You don’t need any extra insulation on the outside. You just go with the 12-inch block and you’re all done, you can do Passive House,’” Bluestone said. “And I say, ‘That sounds great. Have you done it?’ And they go ‘Hubba-da-hubba-da-hubba.’ Have they built a house and monitored it? Hubba-da-hubba-da-hubba. So, maybe in theory, but in reality I don’t know.”

Bluestone isn’t selling himself as a building scientist or researcher, and someone will have to interpret the data he collects in his multi-year experiment. For example, it’s not clear how he will account for variations in local weather conditions — a cold winter one year, a warm winter the next — affecting the amount of energy needed to heat the building. Temporary cladding protecting the mineral wool insulation will have different properties than the permanent stucco finish he plans at the end. That, too, could skew results.

But Bluestone hopes that the project will add new information to what’s already known about the performance of mass walls and, ultimately, advance the use of AAC.

In an email, he recalled an ongoing correspondence with an architect and author who claims that all the data that Bluestone wants about AAC already is available.

“We’ve been kind of like a scratched record (or CD disc) that keeps skipping,” Bluestone wrote. “Needless to say, he has never produced proof of what he has claimed. Perhaps all of this is just my way to prove him wrong? Maybe, but deeper down, I’m looking for the simplest, cheapest, longest-lasting Passive House envelope system that almost anyone can build.”

Similar project nearby

Bluestone’s wood shop project will borrow a few pages from fellow AAC convert Dan Levy, who is nearly finished working on a house and adjacent garage in Woodstock, New York, a town some 50 miles southwest of Hillsdale on the west side of the Hudson River.

Levy’s 2,400-square-foot house is made from 8-inch-thick AAC block insulated on the outside with 6 inches of Roxul ComfortBoard IS rather than petrochemical foam insulation. Beneath the footings is a layer of Foamglas insulation, another non-chemical product.

Walls are insulated to R-34, the ceiling to R-88 with blow-in cellulose, and the slab and footings are insulated to R-34. A preliminary blower-door test showed air leakage at 0.4 air changes per hour at a pressure difference of 50 pascals. Levy says AAC buildings can be much tighter than that and suspects gaps in an ceiling membrane and around plumbing lines could account for his result. He, too, will be looking for PHIUS certification when the house is complete.

Levy is a 64-year-old former professor of industrial education who backed into residential restoration work when jobs in his field dried up. He first used AAC block on an addition to his house in Maryland — just the block and no exterior insulation. He was hooked, and two years ago bought property in Woodstock to build a house there.

“I’ve worked on many old buildings and it’s rare to find an older wood-framed building that doesn’t have lots of areas that have rotted,” he said by phone. “And I thought, if this material does everything I’ve read about, it would be worth trying. It was much simpler than I expected, and it worked better than I expected. I thought it was a great way of starting a business to teach people how to build a better house.”

He chose Woodstock because he knew people there, and he thought a Woodstock address would have enough cachet to help him sell the house, now on the market with 3 acres of land for $750,000. (You can learn more about the Woodstock Passive House by visiting Levy’s website.)

Acceptance for AAC by builders as well as the public has been a tough sell, Levy said. When he completed the addition in Maryland and could point to the many advantages of the material, Levy didn’t get the reception he thought he might.

“Instead, everyone laughed at me,” he said. “Builders said, ‘Wait a minute. You want us to change our entire model?’ The only people who didn’t laugh were the building inspectors. They came out fully briefed, because I had provided everything in advance, and their only question was, ‘Where did you get it? This is great.’ “

4 Comments

Incremental insulation

I'm trying to imagine how the incremental insulation will work... will there be some sort of temporary siding during incremental periods? Steve states he will " find a way to shed water temporarily" but this seems easier said than done. I feel that building 3 or four aac cubes with variable insulation and monitoring them independently might be a better way to get the data sought by this experiment.

Why Not Typical ICF?

Curious as to why they went with AAC which has a low R-Value and doesn't perform as well as traditional ICF with 2.5" EPS + 6" concrete + 2.5" EPS. Plus it's easier to finish the exterior and interior than AAC which doesn't have attachment points and foam.

Maybe ants?

Peter. I for one am concerned about the long term viability of foam as ants move north with the warmer climes...

catching up time....

To Ethan's comment, while discussing this over dinner last night with both Duncan Prahl (IBACOS) and Henry Gifford, Duncan pointed out that the temporary water shedding protocol probably won't work out. I think he (and Ethan) are right on about this. Now, perhaps I'll shift gears and just make this a two part two year study. Bury a bunch of temperature sensors at certain increments in the 8" AAC wall, go through a full heating and cooling season, and then quickly the following fall, add the mineral wool to a depth prescribed by PHIUS, apply the stucco, and measure again for a year.

To Peter: We've built 9 apartment buildings (working on #10 and #11 right now) and 20 something houses with ICFs. Obviously, I like them. Of course I could build the shop with ICF and save my time by not measuring much except for my low energy bills, but my interest in AAC is twofold. First, with the use of mineral wool outboard, for the first time I'll be moving away from foams. Second, ICFs require a bit more technical expertise and know-how to put up. You need a concrete pump. You need to worry about blow-outs. It's not something for the weekend builder to get involved with that easily. AAC can be laid up by a kid. Yes, the reinforcing details and grout introduce a bit of heavier lifting, but it really isn't that complicated, and with a simple electric mixer, some empty compound buckets, a good pipe scaffold and two good backs, most anyone can do the job. Then, applying mineral wool in thick layers is also a fairly simple task. A few long screws with large washers and the job should be almost ready for the stucco cladding. They do this in Europe and Canada, but not so much here. I'm having conversations with Dryvit and Roxul and Sto right now about all of this. As far as I can tell, if it works in Canada, it should work in the northeast in a climate zone #5. The rain should be similar in both locations. They are both wet.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in