Image Credit: Matt Bath

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of blogs detailing the construction of a net-zero energy house in Point Roberts, Washington, by an owner/builder with relatively little building experience. You’ll find Matt Bath’s full blog, Saving Sustainably, here. If you want to follow project costs, you can keep an eye on a budget worksheet here.

Most people these days spend the vast majority of their incomes on housing, especially those who wish to live in a large metropolis with a short commute to work and endless options for friendship, entertainment, and cuisine.

These dwellings consume vast quantities of gas, electricity, and water, which only adds to their high price tags. The supplies of these resources are finite, and their exploitation tends to cause pollution and hardships for wildlife. Building a water- and energy-efficient home is the number one way a person can save a ton of money and help the environment all at the same time.

The problem is that building a house seems like an insurmountable task for the average person. It seems to take an entire army of trades to get the job done, with plumbers, electricians, roofers, framers, masons, and on and on and on. I am setting out to prove that conventional wisdom wrong.

I spent nine months acquiring some basic construction and design skills, and in the process I realized the dirty truth that the average house is not constructed very well. The entire industry focuses on getting the job done as quickly as possible and using paint and drywall to cover up a lack of attention to detail. Just think about it: Every contractor out there is paid by the job rather than by the hour. That encourages them to cut as many corners as they can.

Since the majority of problems with houses aren’t discovered until several years after their completion, it has become relatively easy for them to get away with shoddy work. The drywall crew and painters come by and cover it all up, and homeowners wonder why their heating and cooling bills are so high, why it is so easy for insects to move in with them, and why they can hear and smell everything from the next block over.

The answer is simple. If you peel back the paint and drywall from the average home, you will find a house that is more Swiss cheese than an impenetrable, protective haven. The workmanship is so bad in many cases that I’m willing to bet that anyone willing to invest their time in attention to detail can do a better job. What’s more, you can do it far cheaper, and you can customize your new home as much as you want.

I am an unlicensed beginner. My website is meant to be a resource, not an instruction manual. I volunteered several months of my time to acquire some basic safety, design, and construction skills, and I’d strongly advise anyone looking to build their own home to do likewise. Keep in mind that building codes vary from country to country, state to state, and even county to county. The laws that pertain to the construction of my home may vary substantially from the laws that pertain to you.

My plan is to spend less than $200,000 to complete the project, including tools, truck and trailer.

Buying the land

Where are you going to build your dream home? For me, it was important to find affordable land near a large city. Luckily for me, I was able to find the perfect spot: an affordable, reasonably sized plot near the beach just a half-hour away from one of my favorite cities in the entire world.

I began by making a list of my priorities. I will be building solo, so it was important to have a large city nearby where I could balance my building time with social time. I needed access to basic utilities. To cut out engineering costs, I needed a plot without steep slopes, with decent load-bearing soil. On my wish list was a view and proximity to a beach.

The optimal location became quite apparent when my brother told me about a geographic anomaly by the name of Point Roberts. A quick drive from downtown Vancouver, British Columbia, and just a few hundred feet from its million-dollar, overpriced southern suburbs is a small peninsula south of the 49th parallel that marks the border between Washington State and British Columbia. Home prices below this invisible line are a fraction of the cost of similarly sized homes on the Canadian side, mostly due to a lack of jobs and high schools in Point Roberts. Thanks to help from this website I have no need for a job, and it will be at least 20 years before any future children of mine are in need of a high school education.

Point Roberts had a limited number of lots available, and after sifting through what was available I chose the one that was most accessible. Key factors you might want to consider when choosing a lot include zoning regulations, availability of utilities, whether you’ll have to pay dues to a homeowners’ association, site characteristics, and whether building and/or impact fees will be required for construction.

Preparing the site

Site prep will certainly vary widely, but it basically involves getting all of the services you’ll need during construction. I will be living on my lot at the same time as I am building, so I’m going to need more services to start than someone who has a home away from their lot. In addition, there may be some steps the county requires you to complete before you can even apply for a building permit. All of this information can be found at the county building office or on its website.

While I was lucky enough to find a lot that already had a water meter, I still needed to install a septic system (no sewer connection available), temporary power, internet access, and a temporary dwelling to use for the duration of the build.

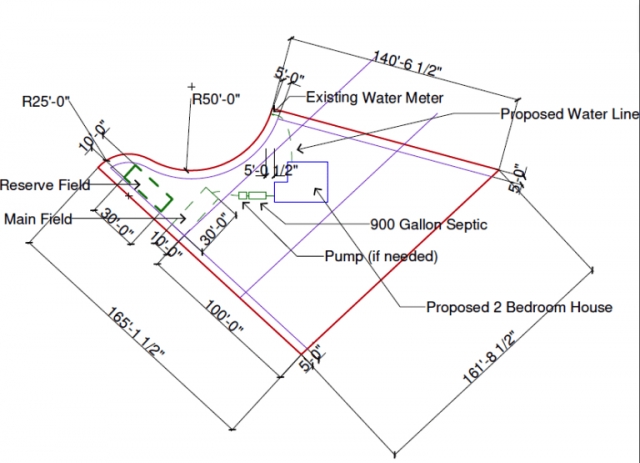

For the septic system, the county requires a licensed engineer to complete the design, but it allows the homeowner to complete the installation. That will give me yet another chance to “Save Sustainably” by installing my own system. As part of my nine-month training, I learned how to use a CAD program called Rhinoceros and used it to design the house. I also used it to create a rough on-site sewage (OSS) design.

I started by researching the local health code. Next, I plotted out the property lines on Rhino. Using the required setbacks, I was able to map out possible locations for the drain field and reserve field. One of the few downsides to the lot I chose is there’s very little legal room to place these fields. My lot measures 16,360 square foot, but only 3,000 square feet was available for a drain field. When all the legal setbacks were taken into account, there was really only one place that the drain field and reserve field could be placed without having to invest a lot of money in an advanced system.

Today, the septic designer came out to do a percolation test and survey the lot. My design is useless without his stamp of approval. He should have the approved design ready in just a couple days, and then the county health inspector will come by and approve it as well. After that, I will be free to start installing it! The process is relatively simple and will involve digging one hole for the septic tank, a second shallower one for the drain field, and trenches for the pipes that will run between them. After that I will drop the tank in and hook up all the piping.

I will be using a pressurized distribution type of system so I also will need to run a power line out near the tank to power a pump. This will need its own separate breaker as well.

A county biologist will visit my lot sometime in the near future and assess what kind of an impact my building will have on plants and wildlife. He can decide to give it the green light or he can tell me I will have to make some changes in order to get the project approved. Obviously I am hoping for the former!

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

10 Comments

Off To A Good Start

Hello Matt

As a builder for too many years I always say to my clients, spend a lot of time planning. A well planned project has a good chance of turning out favorably, a poorly planned one is doomed from the start. What are some of the performance targets you are looking to achieve? How about options for the foundation, walls and roof details, what is appropriate for your area? At 4697 Heating Degree Days you would meet the unofficial definition of superinsulation with R-26 walls (hdd divided by 180) and R-40 (hdd divided by 120) ceilings. In my cold climate (MSP) using the same definition for superinsulation I would have R-43 walls and R-65 ceilings. A house with these specs along with an ACH50 of around 1 would have a heating energy use of about 1 BTU/SF/HDD. The foundation walls and concrete slab must also be well insulated for optimum comfort.

Matt

I look forward to following your build. I'm not sure I agree with your basic premiss though. I've been building for decades. I still can't perform most tasks anywhere near as well as my sub-trades, and although diligent owner-builders may spend a lot of time on things pros don't, that doesn't necessarily translate into a better job. That is primarily because experience teaches us what is important and what isn't. it also teaches us technique - how to perform tasks properly.

The idea that good building is just a few Youtube videos and some research away seems strange to me. You don't generally hear it about other professions, like surgery, law or say baking pastry. I know it stems from seeing shoddy work, but I think just because some trades are getting away with poor workmanship doesn't logically lead to the belief that there is no skill or experience necessary to performing their tasks.

That said: More power to owner builders. I'm speaking from experience. I got started in the trade by building my own home. Having practiced architecture for years I thought I has a good head-start on most DIYers. In the course of that first build I realized how little I knew. If I build that project again today it would be a lot better house.

I only bring this up because I meet a lot of clients who go into the process convinced everyone is out to get them and will do poor work. They have a siege mentality, are reticent to listen to advice from experienced people, and almost inevitably end up with poorer results.

Thank you Doug

I would agree with the planning. I spent hundreds of hours designing the house and planning my build, and that is not including hundreds more hours I spent developing my skills. As far as performance targets go, I want to break .5 in 50 ach, achieve net zero with a modest under 6kW array, and build my first house. I will definitely get down to more specs as I move on towards the insulation in another couple months. If you had a chance to check out the plans you can see I used advanced framing, 2x6 walls with dense pack cellulose, 1 inch exterior rigid polyiso, and .14U windows. Foundation has 2 inches roxul both vertically on the inside of the stem wall and horizontally in a 2 foot perimeter. Ceiling will be 15" blown cellulose with an energy heel to extend it fully to the wall. Hopefully that answers your questions and thank you again for the comment

Questions on Advanced Framing

Was curious on how the building inspectors reaction and comments were as far as your advanced framed home goes? I was reading on this website and they've said in most seismic areas/ high wind areas, some of the advanced framing details wouldn't be sufficiently pass with local codes. Did they ever bring anything up and was there any compromises that you had to make in regards to that?

Appreciate your balanced take Malcolm

There are certainly a great deal of contractors out there that pour their hearts into their work and the end result is a wonderful home. You certainly can't master anything without years of experience, and I'm not in any way looking to stoke the siege mentality you speak of. That having said, if I had a passion in law or medicine or baking, I have no doubt that I could use the wealth of free knowledge available out there to educate myself in those fields. Obviously all 3 require licenses to work with others for pay, but I could certainly suture my own cuts, defend myself in court, and bake for myself at home and if I was focused and passionate, I would most likely be successful. That's what I plan to show when it comes to building. I won't build a better house than a master builder, but I am aiming to build a more efficient, more comfortable, and more personalized home than one built by the average team of contractors that might not be fully invested in the quality of their work. Will I, as you have, realize that I would have been better off using a sub? It's absolutely a possibility, but so far it hasn't been the case. Regardless, I am enjoying the experience and the unique opportunity to educate others on green building techniques.

Matt

Fair enough. I've looked through your blog and it is an inspiration to owner-builders and a tribute to your own tenacity and hard work. I'm looking forward to it revealing a home you love and enjoy living in. That's a remarkable achievement.

On the other hand it's also a chronicle of things learned as you go, mistakes rectified and ways of doing the work that could have been much easier if you had an experienced builder on site. I'll follow along and perhaps we can discuss some of these as things progress.

Windows and doors?

Just wondering what brand windows and doors you'll be putting in? What are the specs for them? Usually triple glazing for a net-zero home.

thanks, Mary

Windows

As with a good deal of my building supplies, I purchased the windows in Canada. I went with Vinyltek out of BC and they are indeed triple glazed. All windows are ER 44 and U.85 (metric) except the north facing windows which are ER 32 (lower SHGC)

Advanced Framing

Rod, I would find it extremely hard to believe that any county would have code amendments that prohibit any advanced framing techniques. You've got to remember that the advanced framing techniques were added to the code in the 70's. There haven't been any problems due to using them that I know of, so there would be no reason to take them out of the code. As far as my build was concerned, the PE didn't bat an eye when he looked at my plans so no, there definitely wasn't any kind of compromise necessary. Thank you for the question!

Passivhaus in a mild climate

I'm a resident of Point Roberts as of March, 2017. I'm a retired mechanical engineer from the University of Texas and moved back to the Pacific Northwest. I got my BSME from Oregon State University in 1982. I'm a friend of Matt's and have been following his project closely. I've helped him out when some extra hands were needed.

Matt introduced me to the concept of Passivhaus, and I'm very interested in it. Here in the Vancouver, BC area, our winters are long, mild in temperature, and wet. Did I mention wet? That being the case, I'm interested in modifying the Passivhaus standard for the marine climate of the Pacific NW. That is, backing off a little on the insulation levels, and putting more emphasis on moisture control. I've read some very good comments on moisture control on this site, and the accepted techniques have evolved over the decades. As most of you know, mistakes have been made.

Matt's project is a very important demonstration of Passivhaus building techniques in our climate. I'm very much looking forward to the finished result, and experiencing it in action. The energy bills will be low. That is a safe bet. The more important factor is occupant comfort. I expect the project to be a success in that area as well.

Matt has really stepped up. He has learned a tremendous amount in many areas of house building. I can say first hand that for Matt, learning and education are his number one priority. This being the case, I'm confident we will be completing the feedback loop and learning from his experience building a Passivhaus in the marine climate of the Pacific Northwest.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in