Roof overhangs and moisture problems in the walls of a house ought to be related, right? After all, most of the water that lands on a house hits the roof first. From there, rainwater runs to the bottom edge of the roof and then makes its way to the ground. (I’m assuming a sloped roof.) Gravity may be the weakest of the fundamental forces, but it dominates with the flow of bulk rainwater hitting the top of a house.

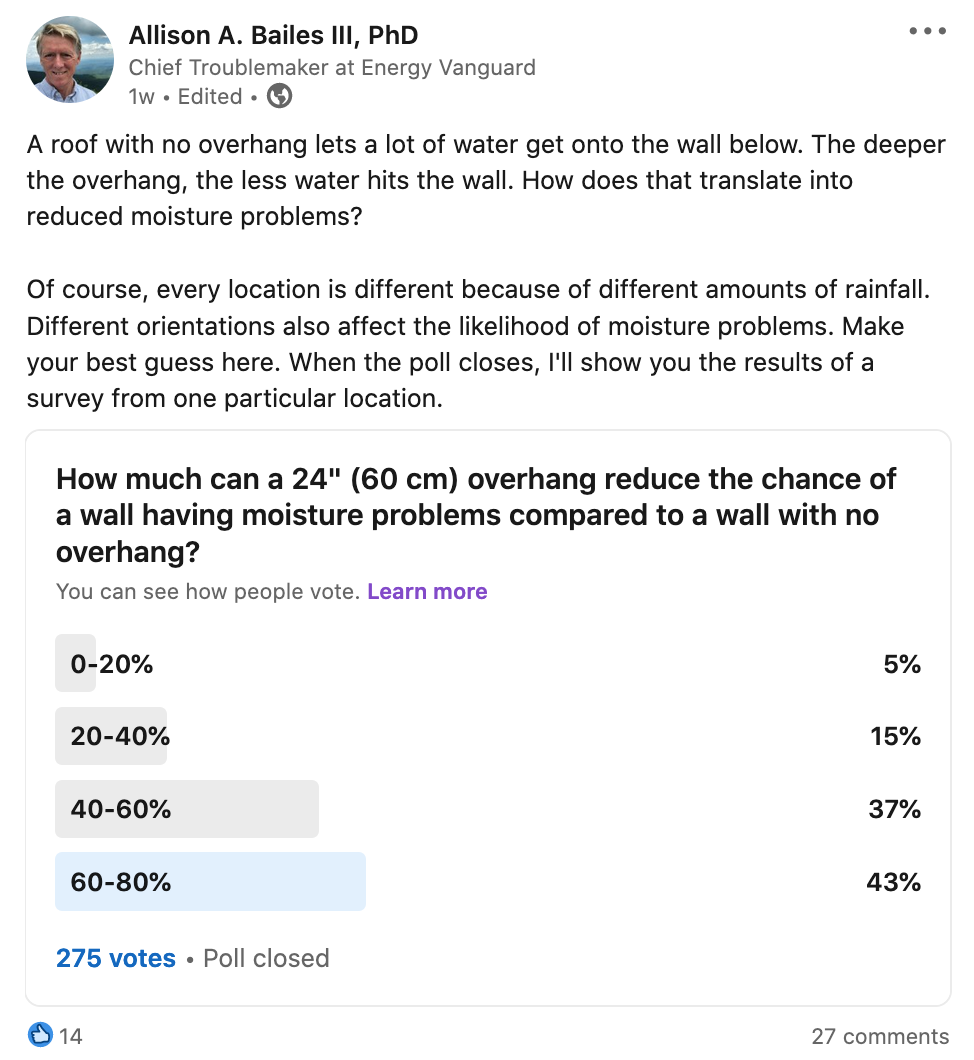

I did a little survey on LinkedIn recently to see how people think of this issue. You can see the screenshot of my question and the results below.

Eighty percent of the people who answered think deeper overhangs significantly reduce the chances of moisture problems. Are they right? Let’s look at the results of a more formal study.

A study from British Columbia

In the 1990s, an interesting study came out of western Canada. Titled, Survey of Building Envelope Failures in the Coastal Climate of British Columbia, it was a survey of 46 low-rise residential buildings. Thirty-seven of those buildings had moisture-related building-enclosure failures. They looked at several factors related to the problems, including:

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

-

Overhang depth

-

Cladding type

-

Drainage plane type

-

Sheathing type

-

Insulation type

-

Orientation

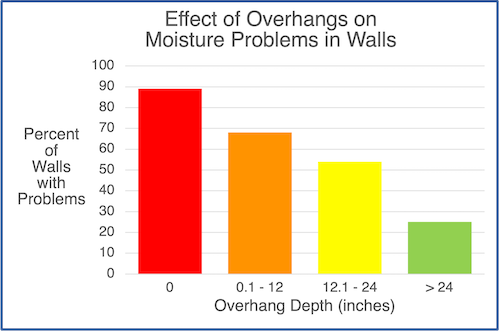

Among the 46 buildings, they studied 72 individual walls. What I found to be the most interesting part of their data was their correlation of the roof overhangs and moisture problems. The chart below shows the percentage of the 72 walls that had moisture problems relative to the depth of the roof overhang above the wall.

Conclusions from the BC study

At the end of the report, the authors list 12 conclusions. Here are what I consider to be the most important of them:

-

Exterior water is the moisture source for the majority, by far, of performance problems.

-

The vast majority of the problems (90%) are related to interface details between wall components or at penetrations.

-

Exterior moisture penetration through or around windows is a significant contributor to moisture problems.

-

Buildings with roofs overhanging walls perform significantly better. [Emphasis added.]

-

In general, buildings with simple details . . . performed better.

If I had written the report, I would have put more emphasis on the effect of overhangs than they did. They found that water from the outside caused far more problems than moisture from the inside. The best thing you can do to keep water off of walls is to extend the roof beyond the walls, and the farther the better. When you keep the water off the walls to begin with, the flashing, interface details, and penetrations through the wall don’t matter as much because they don’t see as much water.

It’s important to keep in mind that this study is from coastal British Columbia. Not only do they have a high amount of rainfall (up to 160 in. per yr. in some places), but the cool weather reduces drying potential for building materials that get wet. In other climates,the results may be different. Also, it is possible to have no roof overhangs and avoid problems by making sure the water management details are designed and installed properly with appropriate materials.

“Down and out” is the rule for bulk-water management

Let’s finish up with a quick review of good water management principles. You want to keep rainwater moving down and out. Overhangs help because they move the water out before it goes down. If the house has no gutters, the water will hit the ground some distance from the house. Then you need a slope in the yard to keep the water moving away. With gutters, the water gets channeled down to the base of the house. Again, you need slope or downspout extenders or both to keep the water away from the foundation.

For water that does hit the wall, this diagram from Building Science Corporation shows the principle of keeping the water moving down and out. Also see the article Rain Control in Buildings by Professor John Straube for more good recommendations.

![Down and out is the rule for water management [Image courtesy of Joseph Lstiburek]](https://www.energyvanguard.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/proper-layering-drainage-plane-flashing-bsc-small.jpg)

Failing to control water

When you don’t have overhangs or good down-and-out water management, bad things happen. I saw the house below near our office a couple of years ago, and you can see they had serious water damage. The large damaged area in the middle (to the right of the window on the left) happened because a lot of water came off the roof in that location.

Not only did that area get the water from the section of roof straight above, but the small gable over the right-side window channeled more water to that location. Without an overhang to move water out and then down, all that water went straight down the front of this house. Poor water management behind the siding led to these problems.

The window on the right was spared the massive downfall from the roof because of the gable. But with no overhang, it got more wind-driven rain. This wall faced west, the direction a lot of storms come from in Atlanta, so it does have moisture damage beneath the window. The damage on the right side also may have been aided by condensate from the window air conditioner.

In short, the depth of roof overhangs and moisture problems are related. Deeper overhangs mean you don’t have to depend as much on the water management details having been designed and installed perfectly.

_________________________________________________________________________

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard. Images courtesy of author, except where noted.

10 Comments

Maybe we should stop calling them "overhangs", since the word "over" implies excess. Here's my proposal for new terminology:

>18": Sufficient-hang

10-18" Almost-sufficient-hang

< 4-10" Deficient-hang

< 4" Mistake

It's also notable that "The vast majority of the problems (90%) are related to interface details between wall components or at penetrations." But that's probably a topic for another time.

Great post, south side of my house has about 33" overhangs, which is also great for shading that side of the house in summer. North side has 20" and west and east are at about 24".

One recommendation, with a standing seam metal roof, if there is no insulation or other material (other than sheathing) in those overhangs, then they make a bit of noise when its raining (or hailing). Over interior space, there's 4" of closed cell spray foam and batts, which makes that part of the roof relatively quiet compared to the overhangs.

Thanks Allison, You would think it was self-evident that sheltering walls would make them less vulnerable to water intrusion, but I was surprised to be involved in a recent discussion here on GBA where that assumption wasn't accepted. Being a denizen of the wet PNW I include overhangs of between 24" and 30". That not only benefits the walls, but helps keep water away from the foundation.

As with open-cladding and flat roofs, the only reason for not having overhangs is architectural preference - and depending on the climate that can be fine, but it comes with the cost of increasing the burden on all the wall components and detailing - and of course increased risk.

The one "con" of overhangs is that in very high winds, the overhangs became areas where the wind can grab onto and cause damage to the roof. The overhangs act like "sails" and wind begins to lift on them, trying to lift the roof with it. In hurricane or tornado zones, large overhangs are bad news when the high winds hit.

For sure - and you can see that reflected in the vernacular architecture of places like the Orkneys and to an extent coastal New England. I think part of the problem stems from using the same wall assemblies without compensating for the increased pressure they are under when overhangs aren't present.

Had a friend that would sail from Sweden to the Orkneys for "fun" with foulies on 24/7. Wimpy me, I'll stick to sailing in the Inner Hebrides ;-)

They are braver than me. My wife's family are from Stroma. Many were wreckers.

What a beautiful and rugged place, kind and tough people. Was in touch with a friend yesterday that bought an old chapel near Inverness (Nairn) that he has transformed into his home. Looking forward to a visit.

Useful report, but building height and wind are a major component. I am involved in the building of a 36’ tall building. It’s not particularly exposed as it is surrounded by other buildings of similar height, but Boston can get quite windy during winter in particular. There is a 16” overhang + a 5” wide gutter bonus for a total of 21” overhang around the entire building perimeter. It took a while before we got all the windows installed so I had a chance to observe the effect of wind driven rain (and snow) on our building walls and openings. Even with a relatively light wind, I was surprised at how much water would end up inside the building on the windward side, including the 4th floor which I thought would get better protection from the overhang. The side away from the wind would get no water inside at all.

My takeaway is that on a building that’s two-story or higher and with some wind exposure, overhangs don’t matter much when it comes to protecting the walls from the rain. I’d focus a lot more on proper gutters and downspout -to avoid having sheets of roof water runoff hitting the wall- and flashing/rain screen detailing.

I've become skeptical in the last few years about what I considered to be an unfortunate design trend amongst contemporary architects, esp in my area of Colorado: trying to achieve a "modern" look that emphasizes primary geometrical forms while harkening back to traditional residential gable roof designs (for market acceptance?) Roof overhangs and eaves are the first victims in this geometry simplifying effort. Occasionally I will note concealed gutters in an attempt to manage drainage but more often they just drain onto the finished siding (see a somewhat famous example from Vermont, and another from my own neighborhood, attached.) Are architects simply relying on rainscreen structures for their bulk water management?

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in