The electrification movement is accelerating, so let’s go back to this topic again and look at how to electrify an older house. In part 1 of this series, I listed some important questions to ask. Today, I’ll cover some steps that can make the transition to an all-electric home easier. I’m not going to get into incentives, but the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) is putting a lot of money out there to help with changing out fossil fuel appliances with electric versions. And that’s not all. The IRA also can help you get the electrical system upgraded if necessary.

But first, let me put a little disclaimer out here. Making changes to your house can be dangerous. It can go wrong in many ways. Working with electricity requires a level of skill and attention that doesn’t suit every do-it-yourselfer. The suggestions I give below are meant to be general advice to get you thinking in the right direction. Don’t take on projects that you aren’t competent to complete. Call an electrician or other qualified professional when necessary.

Plan your conversion

Start with an inventory of your current fossil fuel-burning combustion equipment. Go through the house and determine what fuel is used for your:

- Heating system

- Fireplace

- Water heater

- Clothes dryer

- Range

Once you know where you’re using gas, oil, or propane, you’ll need to decide how far down the electrification path you want to go. All the way? Heating only? All but one appliance?

Once you have that, assess the age and condition of each appliance you want to replace. If they’re old and less efficient than newer models, you have a good incentive to make the switch. You need to replace them anyway, and going to a high-efficiency electric model can help pay for the conversion.

If you’re afraid to switch from a furnace to a heat pump, one thing you can do is go to a dual-fuel system. It heats with a heat pump down to a certain temperature and then switches over to the furnace. See my recent article on dual fuel heat pumps.

Finally, come up with a timeline. Do you want to do it all at once? Or make the conversion over an extended period, say five years? The more you have to do—and spend—to convert, the longer it may take you to get it all done.

Do you need a wiring upgrade?

The big obstacle that can turn what seems like a simple conversion into an expensive upgrade is the current state of your electrical system. Wiring in older homes is often a mess. If your home still uses knob-and-tube wiring (photo below), that’s a mandatory conversion. It’s a fire risk and you should take care of that right away. Get an electrician to evaluate the wiring and see if you need to make any general changes.

Do you need a panel upgrade?

Then there’s the electrical panel. If yours looks like the one in the lead photo above, it’s definitely due for an upgrade. If it looks like a standard breaker box, you may be OK. The next step is to find out what the maximum capacity of the panel is and how close you come to it. New homes these days generally come with a 200 amp (A) service, but older homes may have a maximum of only 100 A or less.

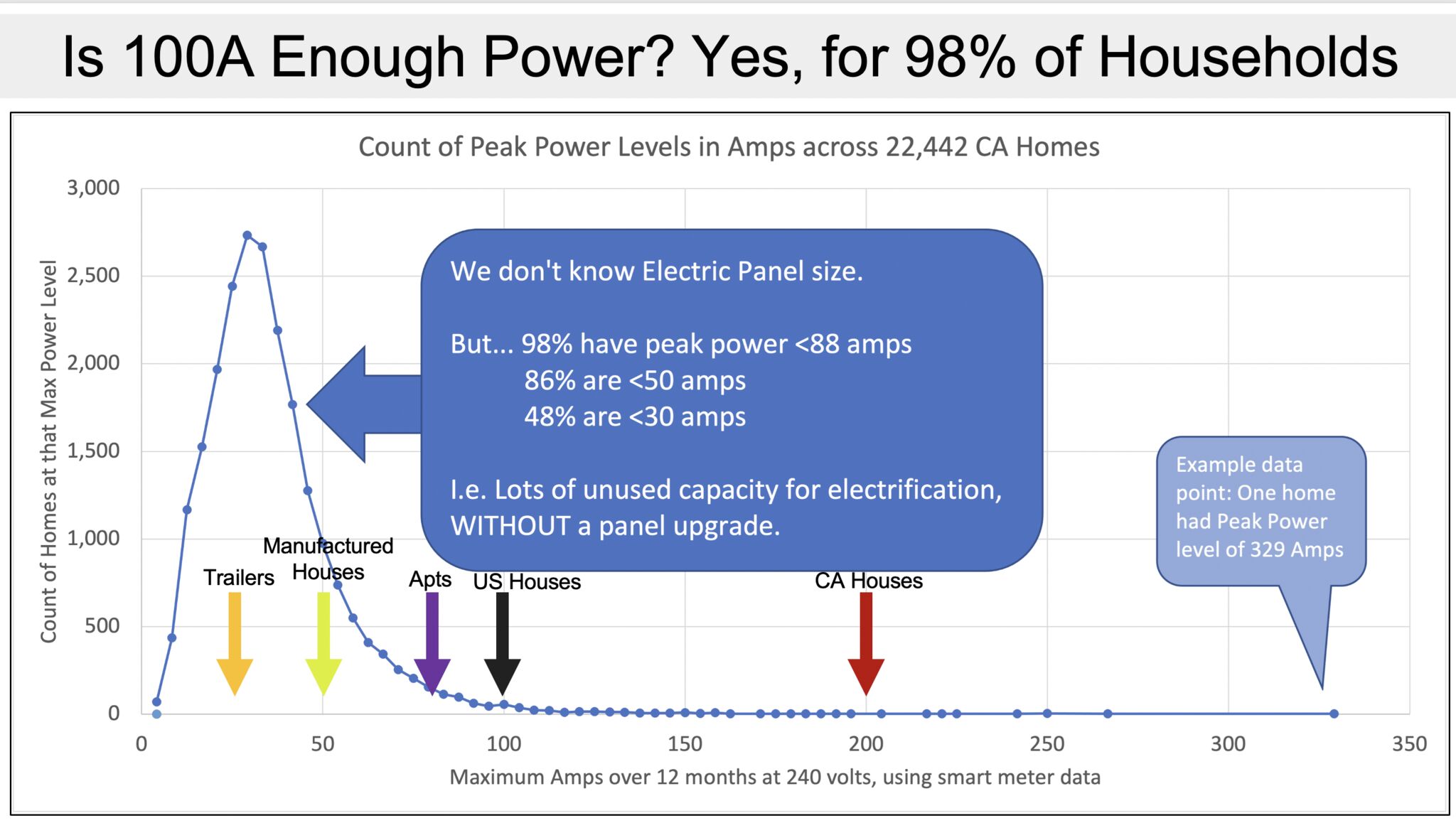

The good news is that a great many homes with smaller electrical services are still OK to go all-electric. Home Energy Analytics got electric utility data for more than 22 thousand customers in California and analyzed their peak power usage. The graph above tells the tale. A measly 2% had peak electrical current greater than 88 A, and 86% had peaks below 50 A.

Find your peak electrical current

That’s great news for those older homes because it means the majority can go all-electric without needing a panel upgrade. Of course, to proceed without a panel upgrade, you’ll need to have an idea of what your peak current level is. Then you’ll have to find out how much electrical load it will add to switch fuels.

For example, let’s say you have a 100 A service, and your measured peak current is 45 A. If the heating and cooling loads are small, you may be able to install an efficient heat pump that adds no more than 20 A. That brings you to 65 A total. That still leaves 35 A, which should be enough to switch to an electric water heater, too. If you want to charge an electric vehicle, though, you may well need an upgrade. Maybe. But see the last section of this article for another option.

One way to get at this is to install a whole-house electricity monitor. I use the Emporia Vue system and have explained the concept of whole-house electricity monitoring as well as written about my first full year of electricity monitoring data. The smartphone app that goes with the monitor allows you to look at the data in units of power or current.

The screen shot above shows the instantaneous current draw in my house on an early September morning when the outdoor temperature is 81 °F (27 °C). We have a 200 A service, and we were drawing only 17 A at the time. (You have to add the A and B currents for the total because the electricity comes in through two mains.)

Map your circuits

One problem you may run into even if you have peak capacity to spare is room in the electrical panel. When you switch from a furnace to heat pump or gas to electric water heater, you’ll need to add circuits. But what if every slot in the panel already has a breaker in it?

I went through the exercise of mapping out all the circuits in my house last year, and it helped solve that problem for me. All the slots in my panel were being used, leaving no room to add more. But when I mapped out every room and electrical load in the house, I found a few circuits that were no longer in use or no longer needed. Also, there were a couple of places where circuits could be combined.

Electrification tidbits

Once you go through the steps above, you’ll have a good idea about how to approach the electrification of your house. Be sure to check out other resources, too. See the Home Energy Analytics page on electrification, where the graph above came from. And a great resource to help you reduce your load is the Watt Diet Calculator from Redwood Energy.

Also, there are a lot of new products that can help. Circuit splitters, for example, let you share one circuit between two loads. Let’s say you already have an electric dryer and want to add a charger for an electric vehicle. A circuit splitter can allow you to add the EV charger without adding another circuit. You plug both into the splitter, and it allows only one to run at a time.

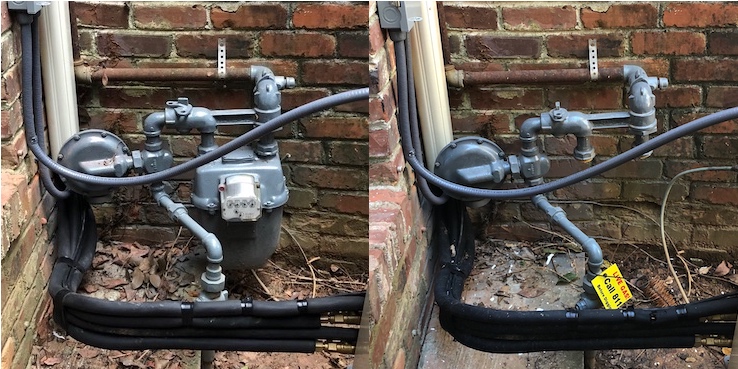

These are exciting times in the world of electrification. I took my house all-electric in 2019 and am loving it for a bunch of reasons—single fuel, combustion safety, indoor air quality, gas. That’s the before and after above, showing the gas meter removed.

Have you already electrified? If not, are you thinking about it?

_________________________________________________________________________

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and is the author of a bestselling book on building science. He also writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. For more updates, you can subscribe to the Energy Vanguard newsletter and follow him on LinkedIn. Images courtesy of author, except where noted.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

20 Comments

theres now 2 in 1 washer/heat pump dryer units that will wash and dry in about 2 hours on a single 20a 120v circuit while also being ventless.

things like that can certainly help when dealing with a lack of circuits or limited service amperage.

With the heat pump, one needs to account for the electric backup heat that kicks in below the heat pumps operating range.

Only if one has electric backup!

Here in California, I believe, there is a code requirement to have a backup heat source. So if you’re electrifying your home it would have to be electric.

Furnaces must have a backup heat source?

Not furnaces. Heat pumps for when the outdoor air temperature drops below where the heat pump can operate efficiently. Many HPs available today can operate at fairly low temperatures, but I think the requirement remains. The temperature where I live (Fallbrook, CA) rarely gets below 30 deg F, and our unit can operate at those temperatures, but we still have electric resistance backup because we got rid of our propane tank. The same thing goes for our HP “hybrid” water heater. Low ambient temperature (it’s in the garage) would greatly reduce its capacity at some point.

It's not code where I live (DC area), but it is generally done with any heat pump installation. It helps to assist heating in low temperatures, or if the heat pump fails (it functions as emergency heat). All in all, a good thing. I have had my heat pump fail on two occasions, and while it is more expensive to heat the house with the 'strip heaters' (resistance heaters), it was welcome.

Another alternative are removable plug-in wall heaters you can bring out for those rare occasions they are necessary: https://www.eheat.com/categories/Wall-Mounted-Electric-Panel-Heaters/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMI9pjV7OaIggMVZs7CBB214gfWEAAYASABEgJeXfD_BwE

A good idea yes, shouldn’t be mandated.

code requirement could be interpreted from CRC303.10

but many ways to address this, in particular with properly sized inverter driven heat pumps.

Not even! looks like any old heat pump satisfies the code requirement. Extremely easy bar to meet, glad it doesn’t actually mandate anything.

One of the greatest days in my memory was when they came and took away the 300 gallon propane tank that was sitting right next to the garage like a huge bomb ready to go off in a fire.

In 1996, the National Electrical Code (NEC) recognized that heat in the system will affect overcurrent protective devices. As such, it defines the concept of continuous loads and the 80% rule to try and offset the effects of heat in the system when sizing a Circuit Breaker.

Continuous loads:

In Art. 100, the NEC defines a continuous load as "a load where the maximum current is expected to continue for three hours or more." This is a load at its maximum current uninterrupted for at least three hours. Most residential branch circuits serve intermittent loads. The numerous branch circuit intermittent loads can appear like continuous loads for panels with a main breaker.

As gas appliances are replaced with electric, and in-home electrical vehicle charging becomes more popular, small electric panels approach the continuous rating of the main breaker.

NEC sizing rules. Secs. 210-22(c), 220-3(a), 220-10(b), and 384-16(c) all relate to the sizing rules for overcurrent protective devices (OCPDs). The first three all specify the exact requirement:

OCPD size = 100% of noncontinuous load + 125% of continuous load.

This formula is meant to prevent thermal overloading of the circuit breakers and the panel. The formula limits the continuous load to 80% of a standard circuit breaker's rating.

For older panels especially, one needs to consider the complete electrical service, including panel, meter base, and service entrance wire size, before adding additional electric loads.

Replying to #8, if that’s truly part of the code and enforced, that’s extremely stupid on CA’s part.

Not that stupid. If you don't have any heat available when the weather is really cold (even if "really" cold is relative), and you need heat, then what's the point of making the conversion?

Because the same issues exist with furnaces and new heat pumps have great performance in the temps CA experiences.

It's not part of the code-- the claim is just wrong

As mentioned in a another comment, California Residential Code (CRC303.10):

R303.10 Required heating.

Where the winter design temperature in Table

R301.2(1) is below 60°F (16°C), every dwelling unit shall be provided with heating facilities capable of maintaining a room temperature of not less than 68ºF (20°C) at a point 3 feet (914 mm) above the floor and 2 feet (610 mm) from exterior walls in habitable rooms at the design temperature. The installation of one or more portable space heaters shall not be used to achieve compliance with this section.

This could be satisfied by some HP systems but, in other cases one need supplemental heating. The system we installed a few years ago is a multi zone system with inverter driven compressor and variable speed fan that would comply with the requirement. We chose to install strip heaters anyway. An undersized or less efficient unit could require supplemental heat. The design temperature here is around 35 degrees. In other, colder parts of the state it would be much more difficult to comply without supplemental heat.

Reply to comment 18

Yes, I said there is no code requirement for backup heat and there isn't. There's a requirement to provide adequate heat. In most of California, you can meet code with a heat pump that has no backup heat.

We completed our electrical conversion this summer, though I thought it was done a couple of years ago. We added one last item this summer. The process started in 2012 , and didn't start out as an intentional conversion (who had heard of "electrification" in 2012?), but became more and more intentional over the years. We don't have natural gas service so we started with propane for space heating, water heating, clothes drying and a propane pool heater that was so expensive to operate we only used it once or twice (we also have solar on the pool and spa). Because our kitchen was already electric our home was built with a 200 amp service. Later de-rated to 175 amps for storage battery installation.

(This is the short version)

2012 - Install 5 kW solar PV on a new patio shade structure.

2016 - Leased plug-in hybrid Ford Fusion

2018 - Replaced propane clothes dryer with heat pump dryer, which operates on standard 120 V circuit; participated in CEC Smart Home study, which provided L2 car charger and 8 kWh battery storage that we were allowed to keep at the end of the program.

2019 - Replaced A/C and propane forced air furnace with high efficiency air source HP; added 2.5 kW of PV capacity; replaced plug-in hybrid with Hyundai Kona EV lease.

2020 - Upgraded battery to 10 kWh (Sonnen) with local control and automatic transfer switch to enable backup capability; added "protected loads" panel to convert to AC-coupled grid tie system; replaced propane water heater with electric hybrid HPWH; PERMANENTLY REMOVED THE PROPANE TANK.

2021 - Increased battery capacity to 20 kWh.

2023 - As part of pool renovation, we added a heat pump heater to supplement solar when we want to use the spa after sundown; replaced Kona EV with Hyundai Ioniq 5 EV.

The battery allows me to manipulate our grid usage to make optimal used of SDG&E's EV TOU rates. Very high (>$0.80/ kWh) during 4 pm until 9 pm summer peak period, but about $0.14 between midnight and 6 am.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in