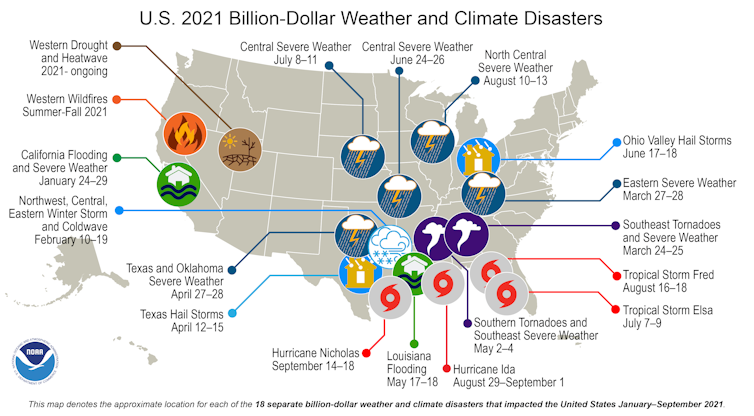

As climate change fuels large-scale natural disasters, the real estate mantra of “location, location, location” is taking on new meaning. In 2021, homeowners have contended with threats including paralyzing cold on the Great Plains, wildfire evacuations in the West and flooding from the South to New York City and New England.

Buying a house is complicated enough in a market that has become supercharged in many U.S. cities. Emerging climate change risks will further complicate those decisions. Investors will be less likely to regret their decisions if they do due diligence in researching local climate risks. Mortgage lenders will face less risk of borrowers defaulting, and insurers will face fewer losses, if they factor climate risks into decisions on loans and insurance policies.

I study environmental economics, and in my recent book, Adapting to Climate Change: Markets and the Management of an Uncertain Future, I explore how the rise of Big Data will help people, firms, and local governments make better decisions in the face of climate risks. I see the emergence of a climate-risk-analysis industry for real estate as a promising development, but believe the federal government should set standards to ensure that it provides reliable, accurate information.

Home prices reflect implicit judgments about whether properties are good investments–including the house and the area around it. For example, the current median home value in California is nearly $720,000–more than twice the national median. This difference reflects a judgment that California offers a desirable climate, lifestyle, and job opportunities.

Prices send climate signals, not everyone listens

People who buy property in California are betting that the state will continue to be a great place to live in the future. If climate change devastates large portions of it, buyers could regret their investment.

Recent research studying U.S real estate shows that flood risk and fire risk are reflected in current housing prices. Properties that are perceived to be riskier sell for a lower price–but it’s not clear whether these climate price discounts fully compensate buyers for the risks they are exposed to.

Concern about emerging climate risks varies, due partly to the partisan divide. It’s fair to assume that some buyers will be eager to purchase homes in locations that others view as too risky. When people disagree about the probability of a bad outcome, the more optimistic bidder is more likely to purchase the asset.

Climate change is making extreme weather events, such as tropical storms and flooding, more frequent and intense in many places. Will people’s risk perceptions shift along with these changes? Studies show that many people underestimate climate risks to housing.

As Nobel laureate economist George Akerlof has shown, asymmetric information in markets–when sellers know more about a product than buyers–can impede trade. Buyers rightly fear getting stuck with a “lemon,” whether it’s a used car or a house that floods with every big storm.

In the auto market, rating systems like Carfax help level the playing field; in the real estate industry, climate concerns are creating an opportunity for a nascent industry of climate risk screening modelers offering similar service for home buyers.

Like Standard & Poor’s but for climate risk

Just as Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s rate private companies’ creditworthiness to help inform investor decisions, a growing set of firms seek to assess spatially refined climate risks, ranging from flooding to extreme heat and wildfire risk. These companies include Climate Check, First Street Foundation, Jupiter Intelligence, Moody’s ESG Solutions Group, and RMS.

Climate risk raters use recent natural disasters to compare the geography of recent flood events to what their model predicts. Typically, they combine peer-reviewed research in climatology and hydrology with a climate-change model to generate risks maps. First Street Foundation has posted a step-by-step overview of its modeling approach.

Like any emerging industry, spatially refined climate prediction has grown unevenly. Some models are scientifically sound and highly precise, while others are lower quality. In a normal market, consumers would select the winning products through market competition–but for climate-risk forecasts, it may take years to assess which offerings are most reliable.

I believe the federal government should play a role in screening the new generation of climate-risk products. Regulators could work with the National Science Foundation to create a jury of experts to evaluate the new products.

One way to quality-check these offerings would be to foster a competition in which teams post forecasts about the likely locations of disasters in 2022, and then are ranked early in 2023 based on how well they predicted actual outcomes. This kind of annual review could nudge participants to upgrade their models regularly. One potential example is algorithmic trading competitions in financial markets, in which contestants develop new models to accurately predict how the stock market will respond to large trades.

Saving lives and protecting assets

Climate-risk assessment firms could help make the U.S. real estate sector more resilient by helping home buyers become more sophisticated and realistic property shoppers. Lending patterns will shift as banks offer borrowers less-generous terms for riskier properties. This incentive should nudge people to bid more for relatively safer properties and to seek to live in less risky areas.

Such shifts, in turn, could nudge changes in local land use and zoning laws to upzone or allow higher-value or denser uses in relatively safer areas. Building more homes in less risky areas would make climate adaptation more affordable.

Climate change confronts people with fundamental uncertainty. I see developing the skills and infrastructure to better predict local climate risks as a useful strategy for adapting to climate risks. If forecasters can develop trusted predictive models, people will face less future regret about their real estate investments and less risk in their daily lives.

Matthew E. Kahn is Provost Professor of Economics and Spatial Sciences, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. This post originally appeared at The Conversation and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

5 Comments

Thanks for posting. I remember when the catastrophic futures pit opened on the CBOT (https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/catastrophe-futures.asp). In general, those that take the risks should be covering the costs. This past summer I looked into the wildfire industry, a lot of federal tax dollars flowing to private contractors using antiquated equipment (including 1950s, 1960s military surplus), at times to protect private property. A well-known issue in that industry is "mission mentality", which is accentuated by the thought that private property and lives may be at risk. If private property owners were to more fully address their own wildfire risks, perhaps we could lessen mission mentality and get more rational local and national strategies - that spend taxpayers dollars more wisely and, at the same time, increase safety of the wildfire teams. There's a website dedicated to wildfire helicopter and plane crashes. And, increasingly such aircraft, many modified and unregulated by the FAA, are flying over dense urban zones. Heightened risk management is warranted.

We also need to build much better, homes and buildings with low energy needs. The building sector, transportation, agriculture and industry must make progress. Minimizing global warming should be the priority on all fronts to stave off the climate threat.

Yes, "build much better homes and buildings with low energy needs" - and/or rehab existing, under-performing ones.

We recently bought a semi-fixer-upper, 60's, all-electric rancher w/ a dysfunctional, grid-tied solar array with the goal of making the house live w/in the production of the 10kW array (effectively net zero?).

For much less than the cost of a new Gashog SUV, we: Repaired the solar array; Installed new cool-roof shingles (needed replacement anyway); Did an energy audit, sealed the leaks and upped attic insulation to R50+; Installed new windows and insulating blinds w/ sidetracks; Replaced the original baseboard heaters w/ ceiling and cove radiant heaters (a terrific form of heat, plus the units are rock-simple, need zero maintenance and last forever); : A wood-burning fireplace insert for emergency heat during power outages and; Upgraded to a heat pump h2o heater.

In the first full calendar year (with many of the upgrades done during the year, so not a full year's benefit), we more than doubled the solar production and slashed consumption by nearly 30%. For 12/2021, our first big heating month, our electric use was 55% that of 12/2020 and we're looking forward to similar savings in Jan/Feb/Mar/2022.

Next step will be an EV that'll support V2H so we can use it as battery backup for our solar system. We estimate that we'll produce enough extra kWh's to cover 7k miles in the EV (more than we now drive) and still be within the solar system's production.

For icing on the cake, we have a grandfathered SREC contract that generates $4,800/yr in Energy Credits. "Free" electricity, "Free" driving and $4800/yr in income - what's not to like?

Of course the devil is in the details. One side will surely campaign that taxpayers MUST subsidize the risk out of altruist-collectivist reasons.

Indeed, I hear commercials for ACA health insurance premiums at $52 per month, when my spouse and I pay $1,700 per month on a crappy "Silver" plan. The ACA was a political tool to spark inflation (skyrocketing costs), ensure hefty profits for insurance companies (i.e., a percentage of costs), and shift risk in a manner that screws small biz owners. Politicians and lobbyists love altruist-collectivist reasons to line their pockets.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in