This article was written by Zachary Lamb, Jason Spicer, and Linda Shi and first appeared at The Conversation.

When you hear the words “trailer park” or “mobile home park,” what comes to mind? Crime? Poverty? Vulnerability to natural disasters? These negative images reflect the stigma, reinforced by popular culture, that many U.S. residents assign to manufactured home parks—the official name for these dwellings under federal standards adopted in 1976.

Over 20 million Americans live in manufactured housing—more than in public housing and federally subsidized rental housing combined. Yet many people, including urban planners and affordable housing researchers, see manufactured housing parks as problems. In contrast, we see them as part of the solution to housing crises.

We are urban planning scholars who study climate vulnerability, community economic development, and equity in urban land use. Our research suggests that misguided stereotypes blind scholars and policymakers to the possibility that mobile homes can help address the affordable housing crisis and climate change. Here are some misperceptions about this widespread form of housing.

Stereotype 1: Manufactured housing is shoddy

Many people think manufactured homes are poorly built, even though these structures, unlike site-built houses, have had to meet federal safety standards since 1976. These safety standards have been periodically updated, often in response to disasters. Today, new, well-installed factory-built homes are comparable to site-built homes when it comes to standing up to wind, fire, and other disaster threats.

Compared to homes built on-site, manufactured housing costs half as much per square foot—partly because it’s easier, more predictable, and cheaper to build homes in factories. Many quality problems associated with manufactured housing arise from home installation, park maintenance, and infrastructure issues. No matter how well-built homes are, residents can suffer if they are installed on unstable foundations, or if park owners allow water, sewer, or power utility infrastructure to crumble.

Stereotype 2: Housing parks are always exploitative

While many manufactured housing residents own their homes, they may not own the land the homes sit on. This can leave them at the mercy of predatory park owners and investors. Moving manufactured homes is difficult and expensive, despite the “mobile” label, so residents of manufactured home parks can’t easily relocate when park owners allow conditions to deteriorate, raise rents, or evict residents.

But there are alternatives. Residents at more than 1000 manufactured housing parks in the U.S. have jointly bought their land, creating Resident Owned Communities.

This cooperative model gives residents control over their homes and neighborhoods. Resident-owned parks preserve affordability and help residents address their own problems, including vulnerability to climate-driven disasters.

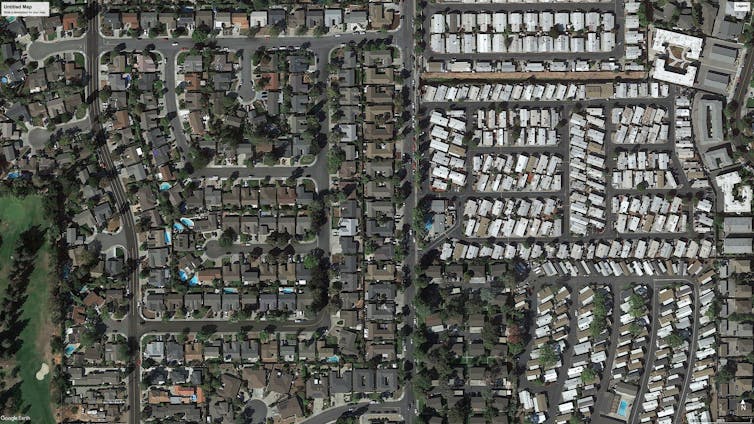

Stereotype 3: Housing parks aren’t urban or dense

Manufactured home parks are often dismissed as rural and low-density, and therefore irrelevant to urban housing needs. However, 61% of all manufactured housing is located in a metro area, and 8% is in urban centers.

The density of these communities, typically eight to 15 homes per acre, is often greater than nearby neighborhoods. In Houston, for example, many manufactured housing parks are located in suburban areas close to the central business district. If anything, local zoning in many cities limits the density of manufactured housing parks.

Stereotype 4: Housing parks are uniquely disconnected

Critics often assert that manufactured housing parks are disconnected from surrounding neighborhoods. In reality, this pattern applies to most U.S. residential neighborhoods built since World War II, including gated communities and cul-de-sacs. Residents of these communities value the privacy, safety, and neighborhood cohesion their street patterns provide.

Biased local zoning regulations also frequently reinforce manufactured housing parks’ isolation by requiring them to be separated and hidden behind tall privacy fencing. Where fragmented street networks create problems for residents, like reduced walkability, they can be retrofitted by reconnecting streets.

The real challenges

While these stereotypes often don’t reflect reality, manufactured housing communities face real challenges.

Local governments and park owners often are eager to convert parks to what they describe as “higher and better uses,” which frequently means evicting residents for commercial development or more expensive housing. Private equity investors, pension funds, and sovereign wealth funds are buying up manufactured housing parks, which they view as reliably profitable investments. When owners redevelop parks, they can evict residents with little recourse.

Residents of manufactured home parks are also increasingly vulnerable to climate change impacts. Biased zoning rules have forced many of these communities to locate on less desirable land, including flood-prone sites, industrial areas and highway fringes. In a 2021 review, we found that 22% of manufactured housing parks across nine states were located within current 100-year floodplains—zones with a 1% chance of flooding every year.

Manufactured housing is especially common in hurricane-prone regions like Florida, Louisiana, and Texas. While updated building standards have substantially improved safety, increasingly ferocious storms still pose a real threat.

Aging manufactured home park infrastructure, including sewer, water, and electricity systems, is highly vulnerable to extreme heat, wind, drought, flooding, and wildfires. And since residents typically have lower incomes, they have fewer resources to respond when extreme events strike.

Manufactured housing, resilience, and justice

With economic, political, and technical support, evidence shows that manufactured housing can overcome these challenges.

To date, 20 states have adopted laws that help residents purchase the manufactured home parks where they live. These policies have helped ROC USA, a nonprofit social venture, create a network of over 280 cooperatively owned, limited-equity, resident-owned communities that are home to over 18,000 households.

ROC USA provides low-cost loans to resident cooperatives to buy land and make needed capital improvements such as upgrading water, sewer, and electric systems. Their network of regional housing experts then works with communities for at least a decade to develop and sustain their ability to manage their parks.

Over three decades, no ROC USA community has ever defaulted on a loan or sold their park. A growing number have adopted climate-responsive measures, such as building storm shelters and community centers, upgrading drainage infrastructure, and providing emergency post-storm tree clearance and other forms of mutual aid. Other resident-owned communities are investing in renewable energy and energy efficiency, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and energy costs for their residents.

Policymakers are paying attention. The Biden administration’s 2022 housing plan includes extensive support for manufactured housing parks.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom has called for increasing state funding to preserve manufactured housing parks as affordable housing. The U.S. Department of Energy recently adopted more ambitious efficiency standards to reduce energy costs for residents of manufactured housing.

In our view, these efforts should be coupled with legislation that protects manufactured housing park tenants and expands the limited-equity ROC model. Governments could enact laws that offer tenants opportunities to purchase their rental units and provide subsidized loans and grants to resident cooperatives. Decades of experience shows that resident ownership can transform manufactured home parks from sites of stigma and vulnerability into stable and resilient communities.

Zachary Lamb is an assistant professor of City & Regional Planning at the University of California, Berkeley. Jason Spicer is an assistant professor of Geography and Planning at the University of Toronto. Linda Shi is an assistant professor of City and Regional Planning at Cornell University. This article was originally published at The Conversation.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

7 Comments

Thank you so much for this post. Because manufactured homes remain relatively affordable, our society rejects them. We don't like poor people who settle short of the "American dream" of middle-class housing. Despite these cultural (and moral) shortcomings, it's good to know the facts: These factory-built houses are perfect homes, well-built, and represent the only non-subsidized solution to the housing crises. The "trailer park" communities are tight-knit, friendly places -- the envy of neighborliness. Some architects, such as Andres Duany, have designed very chic versions that would accommodate the aesthetic needs of the most style-conscious millennials (and boomers). I am thrilled to read this in GBA.

Here's what I wrote on this topic in 2017: "Perhaps the greenest option for those on a budget is to purchase a trailer or manufactured home in a trailer park. The quintessential trailer park reached its apogee in Florida; the best of these communities include common facilities like playgrounds or swimming pools. By now, this type of living arrangement can be found in almost every state in the country. Trailer park communities have many of the advantages of cohousing communities at a fraction of the cost. And since these homes are small, energy use is low."

I agree - although trailers and manufactured homes aren't synonymous.

Unfortunately many trailers are poorly build and both degrade and depreciate quickly. That's very unfair to those who can't afford to replace them, and don't get the advantage other house owners often enjoy of seeing their investment becoming more valuable over time.

The nomenclature of factory housing is confusing to those that have not studied the various classes: Camper trailers are not meant for long-term living, although the housing crisis has made them for many who need housing close to work or at least off the street. Park models are a step above camper trailers, and they were designed for seasonal housing, and usually, parks limit residence to six months. Tiny homes on wheels fall between the trailer and park model. Light enough to two behind a pickup truck but comfortable enough for long-term living. Manufactured houses are the subject of the article posted here. These move from factory to site. Sometimes they remain mobile because they could be towed behind a tractor to another site, although at a high expense. At other times they are placed upon a permanent foundation and become real property, like a site-built house. Modular homes are regular houses built to the state codes and assembled on a permanent foundation. These have existed since the 1800s and were primarily responsible for the quick construction of frontier towns (shipped to Kansas by train from Cincinnati, for example). The modular home on a frame is a hybrid between the manufactured house and modular homes, usually constructed by the same companies that build the latter. Nowadays, some of the most popular applications of modular construction include hotels and apartments. In the Colorado mountains, modular has become a ready solution for the short building season. "Mobile homes" proper now designate factory houses built for long-term

living before 1976. Many of them were indeed shody.

Fernando,

They do get lumped together as though they were a single class of housing, while as you say they share very different attributes. Unfortunately the authors of this article do that too, talking about manufactured homes to make some points, but dealing with the larger issues that have n0thing to do with which type of small housing they are referring to.

I think trailer parks are a mistake. Segregating one housing type, or housing from other uses, is poor urban planning, and leads to both a lack on integration with their surrounding communities, and stigma.

As long as any of these housing types are seen as still being somewhat mobile and easily movable, the problems of tenure will merit. Whatever the type, they need to put down permanent roots and become part of the community's fabric.

I looked into buying a manufactured home a few years ago and even toured a factory. I came away thoroughly impressed on how high quality they were! They are not the double-wides I remember from my youth and are even notably better made than many of the tract homes built as a matter of course around here.

Manufactured homes were common for awhile around here when buying land and needing a house on it in a hurry. Many/most of them are still around. On a proper foundation with all the utilities coming in via normal means and sitting on owned land, it typically takes some sleuth work to even determine that the home is manufactured in the first place.

But that's not really what this article is talking about with its focus on trailer parks. There are a lot of those around here, too, and they are all abysmal. Trailer parks around here are for people that can't even afford apartment rent. Keeping rent that low means also keeping the standards of the park incredibly low. Upgrading the park to a reasonable level means also jacking up the rent significantly and that prices out a notable number of the residents.

Kurt,

Some manufactured homes are really high quality, but once provided with the same foundations and services as site built houses, what they are not is half as expensive to build.

That's what I find a bit annoying about this article. When you buttress your preferences with arguments that conflate different things, or are factually just plain wrong, you lose me.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in