Image Credit: Interstate Renewable Energy Council and GSE

Over the past four days, the New York Times and industry news source RenewableEnergyWord.com have published stories that indicate solar power adoption in the U.S. is increasing, if sometimes plodding.

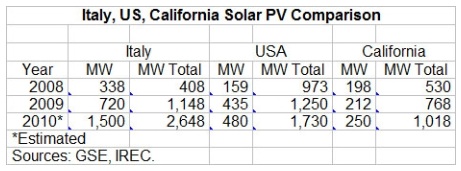

The RenewableEnergyWorld post, for example, cites a draft report by the nonprofit Interstate Renewable Energy Council that highlights the relatively rapid solar adoption rate in Italy. In February 2007, Italy replaced a program offering tradable green certificates (based on the megawatts of power generated by a solar installation) with a feed-in tariff (FIT) program, which pays an above-market rate for solar-generated electricity fed back into the grid.

Responding to FITs

Italy’s FIT program seems to be working: the country is on track to see 1,500 MW of solar power installed by the end of 2010. The U.S. is no stranger to the FIT concept, of course, but FIT programs here have been deployed regionally rather than nationally and sometimes involve complex calculations – based on the rate schedules of the utility companies serving FIT participants – to determine the payments customers receive when their solar installations feed power back into the grid.

More often than not, FIT schemes in the U.S. work, but the program in Italy seems to be working better. According to the IREC report, in 2009 Italy installed 740 MW of solar power (most of it on rooftops, the REC story notes), while the U.S. installed 435 MW. A more pointed comparison in the IREC report is that Italy (population: about 60 million) averages 250 MW of added photovoltaic capacity every two months, which is more than the PV capacity being added in a year in California (population: about 40 million, and one of the biggest PV markets in the U.S.).

Private investors pay attention

Still, interest in solar power for residential customers in the U.S. isn’t drying up. A recent post on the New York Times Green blog page focused on a $55 million investment, led by venture capital firm Sequoia Capital, in San Francisco-based SunRun, which leases rooftop solar power installations to homeowners. This investment round, announced on Tuesday, was the second for SunRun that included Sequoia and other investors, who had earlier approved $30 million for the firm. SunRun and a Silicon Valley-based competitor, SunCity, also are tapping into tax equity funds – of $100 million and $190 million, respectively – set up for them by utility holding company PG&E Corporation and U.S. Bancorp, the Green blog notes.

“We’re seeing early signs of an inflection point in the market where the cost of offering a solar solution is becoming cheaper than utility pricing,” Warren Hogarth, a partner at Sequoia, told the paper. “We’re moving from people buying solar because it’s a nice thing to do to buying solar because it makes economic sense.”

A renewable-energy program stalled by Fannie, Freddie

One increasingly popular financing mechanism for residential solar has been the Property Assessed Clean Energy bond, whereby money raised through municipal bond issues is loaned to homeowners for solar installations, with the debt added to the property’s tax bill. The debt, amortized over 20 years, stays with the tax bill if the property is sold.

So far, 22 states have authorized the use of PACE programs, and the Department of Energy has allocated $150 million in stimulus funds to help municipalities set up and administer PACE programs, many of which become fully subscribed quickly. A key feature of PACE loans is that they, like most special property taxes levied by municipalities, have “super-priority lien” status, meaning they take priority over whatever private financing a homeowner may have, including a conventional mortgage. This encumbrance, as a recent New York Times story explained, is not viewed favorably by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the two companies that guarantee most residential mortgages. The super-priority energy-related liens, Fannie and Freddie worry, will further burden taxpayers if the homeowners default on their mortgages, since property taxes take first priority when a foreclosed property sells.

On May 5, the Times notes, the companies sent letters to mortgage lenders to remind them that “an energy-related lien may not be senior to any mortgage delivered to Freddie Mac.” Beyond that, though, mortgage lenders were offered no further guidance on the issue, which has communities shying away from PACE over fears that lenders who sell loans to Fannie and Freddie will no longer approve first mortgages or refinancing unless the homeowners first pay off their PACE program loans.

A general counsel for one of the housing agencies told the paper that it is “working expeditiously” to respond to concerns by PACE program supporters – a group that includes, most prominently, the Obama Administration. That Fannie and Freddie decided to focus on PACE loans, rather than any number of special property taxes that communities may impose, puzzles state and local officials.

Ben Pearlman, a commissioner for Boulder County, Colo., said that the county had financed energy-efficiency upgrades and solar installations for 600 homes but suspended its residential program because of the Fannie and Freddie letters.

“Because they touch so many mortgages in this country,” he said, “it makes it impossible for us to proceed.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in