This article, originally published at The Conversation, was written by researchers from Stanford University, Australian National University, and the University of California, Los Angeles: Krishna Rao, Alexandra Konings, Marta Yebra, Noah Diffenbaugh, and Park Williams.

The view from the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in California can be beautiful—pine forests and chaparral spill across an often rugged landscape. But as more people build homes in this area, where development gets into wild land, they’re facing some of the highest risks for wildfires in the country.

The type of trees, plants and grasses at any location will influence how likely the area is to burn. However, our new research shows that some areas of the wildland-urban interface—the land where development ends and wilderness begins—are at much higher risk of burning than others. A key reason is how vulnerable the local vegetation is to drying out in a warming climate.

In a study published on Feb. 7, our team of climate scientists, fire scientists and eco-hydrologists mapped out where vegetation is creating the highest fire risks across the western U.S. We then compared that map to where in the region people have been moving into the wildland-urban interface.

We were surprised to discover that the fastest rate of population growth by far has been in the areas with the highest fire risk. This includes several areas in California, Oregon, Washington and Texas.

Plant sensitivity has a large effect on fires

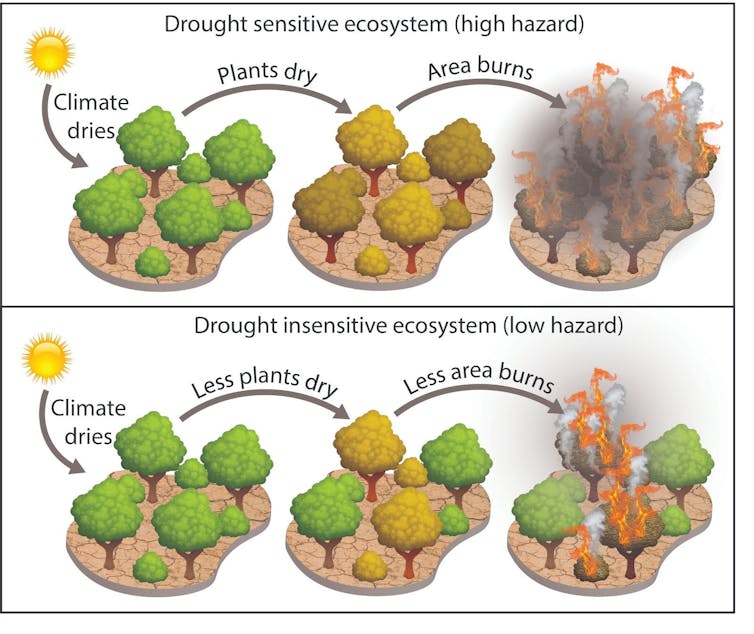

When a fire does break out, the amount of area that burns increases significantly if a region’s vegetation is drought sensitive, meaning it dries up easily after periods of little rainfall and hot temperatures.

Just as a succulent is better at surviving a water shortage than, say, a citrus tree, some vegetation loses moisture more quickly in dry conditions. Such diverse sensitivity can have a strong effect on wildfires. In fact, we found that under the same increase in droughtlike conditions, burned area increases twice as much in the most sensitive regions as the least sensitive regions. As a result, fire hazard in regions like California, eastern Oregon, and central Arizona has far outstripped the average. But what about human exposure to wildfires?

(For more on building details for a wildfire zone, see this article by Joseph Lstiburek of the Building Science Corp.)

The wildland-urban interface population boom

We found that while the number of people living in the wildland-urban interface overall roughly doubled from 1990 to 2010, the population in its highest-hazard regions grew by 160%. As more people move into these areas, the opportunity for fires to ignite rises, as does the number of people at risk.

In all, the population of those high-hazard areas grew from 1 million in 1990 to 2.6 million in 2010, the latest year with detailed population data. That’s an increase equivalent to the current populations of San Francisco and Seattle combined.

More people still live in the low-hazard regions of the wildland-urban interface, where the population grew 107%, from 5 million in 1990 to 10.4 million in 2010, but the high-hazard regions have seen much faster growth.

We don’t know what is causing the population boom in these highly sensitive areas of the western U.S. Building codes, timber-dependent communities and people seeking homes surrounded by forests may have contributed to the expansion of the wildland-urban interface, but those factors alone don’t explain why population would rise the most in the most vulnerable regions.

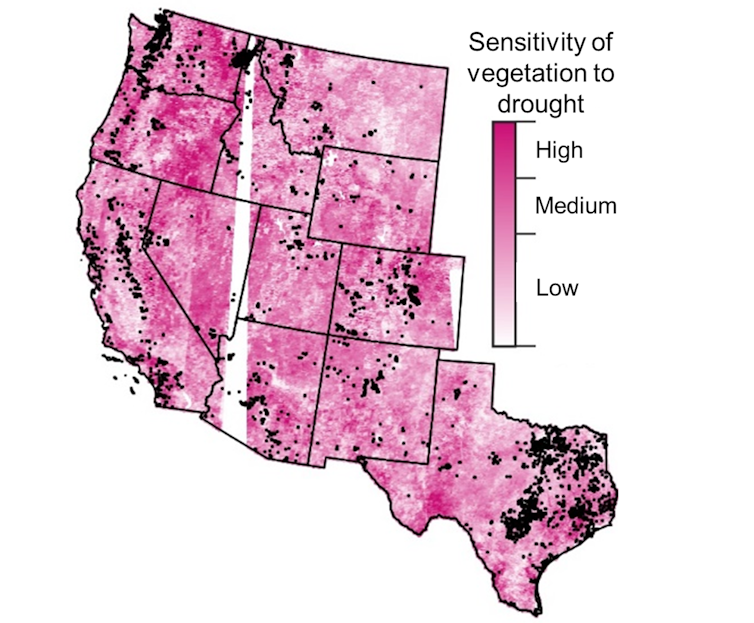

However, a map of vegetation’s sensitivity to water shortages can provide some insight. By linking satellite-based estimates of vegetation dryness to climate observations, we created continental-scale maps of vegetation moisture. For the first time, we now know the precise locations of the most drought-vulnerable and hence fire-prone vegetation.

The map shows that the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in Central California, the outskirts of the San Francisco Bay Area, San Diego and San Antonio all have drought-sensitive vegetation and saw populations expand in the wildland-urban interface.

Further studies examining the demographics and local land use and development regulations in such regions can shed light on the drivers of growth in these high-risk areas. In the Bay Area, for example, a lack of affordable housing has pushed people farther from cities and may be encouraging more development in the wildland-urban interface, including high-risk areas that hadn’t previously been developed.

What can people living in high-risk areas do?

The disproportionate population growth in high-hazard areas is a warning that the likelihood of humans sparking a fire in an area with high-risk vegetation is rising–and that it may be higher than was previously understood.

Community leaders can use this knowledge to identify where human activity overlaps with drought-sensitive regions to improve local land-use planning, prepare firefighting resources and develop safer evacuation routes.

Property owners can keep a safe defensible space of at least a 100 feet of nonvegetated land on all sides of a home to help protect their structures when wildfires occur. Retrofitting homes using fire-retarding materials or double-paned windows can help too.

Preventive measures like these can limit the ballooning losses from wildfires, including devastating air quality due to wildfire smoke, while also allowing humans to more safely coexist with natural fires.

Preparing homes for wildfires can take months, so it’s important to use the winter, when many of these areas have their wet seasons, to be ready by the time the land dries out and wildfires ramp up in spring.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

5 Comments

[We don’t know what is causing the population boom in these highly sensitive areas of the western U.S. Building codes, timber-dependent communities and people seeking homes surrounded by forests may have contributed to the expansion of the wildland-urban interface, but those factors alone don’t explain why population would rise the most in the most vulnerable regions.]

Really? Simple. It's the lower cost of living compared to that of nearby urban centers.

"As more people move into these areas, the opportunity for fires to ignite rises, as does the number of people at risk."

Urban firefighters are trained to handle structure fires where people might be present. Wildfire/wildland firefighters are trained to handle wildfires. If someone wants to live in a wildland area prone to wildfire, I say pay for fire protection yourself, don't put wildfire/wildland firefighters at increased risk.

Let's see a proper assessment of costs.

Spoken like a true Communist. Rural areas usually have local county firefighters and residents pay county taxes to cover the costs. Assessing more fees and forced taxation is not the solution. More firefighters were seriously injured during the riots/protests in the past few years than fighting rural wildfires. Maybe urban area residents need to pay more fees to cover these increased risks for living in riot zones. Let's see a proper assessment of costs for urban areas....

Did not mean to offend, but your statement about "seriously injured", does that include "death"? I find this site informative https://wildfiretoday.com/tag/crash/?sfw=pass1648688158

I know people that are risking their lives in the antiquated military surplus equipment (helicopters and air tankers), which are flying directly over my densely populated urban area at low altitude (say 500 ft to 1500 ft, lower than commercial flights). I say more tax revenue for them and better equipment too. Their mission does not involve "saving" rural structures or people yet people are increasingly the source of too many of the wildfires - that's a problem (I think what the article was addressing in part).

Good idea on the riot zone living too. We can agree on that.

In the county where I live, the city has 95 FTE firefighters, the rural district has 52 FTE firefighters, and property taxes in the county pay for both. Taxes keep going up to fund rural as risks are increasing. Guess I pay for that . . . .

I'm currently working on a deep energy retrofit on a SFR in a high fire risk area in southern california, and including as many details as possible to make the structure more fire resistant.

Reroofing right now with Owens Corning's Titanium FR under a heavy clay mission tile roof, with WUI-approved fire-treated spruce shiplap for eaves.

Since we're re-using the existing tiles, the roofer wants to use Dupont Tile Bond instead of fasteners so they dont have to drill out the mortar - how high of fire risk is it using Dupont Tile Bond throughout the roof? Feels like its a lot of flammable foam to add to a roof assembly we're being careful to protect against fire.

Dupont says the following:

CAUTION: This product is combustible and shall only be used as specified by the local building code with respect to flame spread classification and to the use of a suitable thermal barrier.

The cured adhesive product is combustible and may present a fire hazard if exposed to flame or temperature above 240°F(116°C).

Thanks.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in