We may be coming out of the cold part of the year here in the Northern Hemisphere, but that’s no reason to avoid talking about wintertime indoor humidity. There’s been a lot of discussion in the past couple of years about what the bottom end of the humidity range should be—40%? 30%? 25%?

I’m certainly no fan of bone-dry air, having experienced too much of it when I lived in an old house in Philadelphia. But I also know that keeping the humidity too high in winter can cause problems. Harvard University, in fact, once had to tear down a 17-year-old building because of bad advice about indoor humidity.

The cause of bone-dry indoor air

Before I jump into that debate about indoor humidity, let’s first look at why the air in your house might be so dry to begin with. I’ve covered this before, so I won’t go into all the details here. Here’s a quick rundown of the causes of dry indoor air in winter:

- Cold air is dry air. The lower the temperature, the less water vapor will be floating around in the air.

- A leaky house allows a lot of cold, dry air to come in and mix with your indoor air.

- Two of the driving forces behind air leakage are wind and the stack effect, both of which can be higher in winter.

- When cold, dry air leaks into your house, it lowers the indoor relative humidity.

- The leakier your house is, the drier the indoor air will be in winter. Also, the more you ventilate the house in winter, the drier it will be.

Clearly, all this means that the first step to keeping your indoor air from being too dry in winter should be air-sealing. It’s a pretty simple concept, right?

A humidifier can help

Unfortunately, many people don’t understand the reason their indoor air is dry in winter. So they don’t jump to the logical conclusion of stopping the bleeding. Instead, they put a Band-Aid on the open wound: They start adding water vapor to the indoor air with a humidifier . . . or two or three.

Yeah, that can raise the indoor humidity. If you throw the right amount of humidification at it, you may even get to a reasonable indoor humidity. For a leaky, poorly insulated house in a cold climate, that reasonable humidity might be only 30%.

But it’s gonna cost you. Running a humidifier isn’t free. It takes energy to get that water into the air. And as you keep humidifying the air in a leaky house, that now more expensive air keeps leaking out. Then you have to humidify the new dry air that leaked in.

Clearly, reducing the air leakage should be your first priority in keeping your indoor air from getting too dry. Then humidify, but not too much.

Humidity advice from health experts

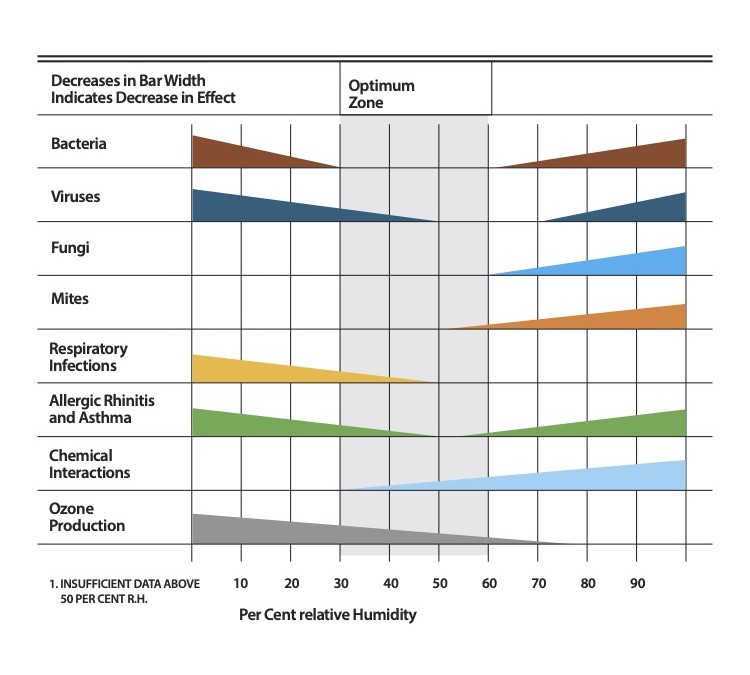

We’ve all been living through the COVID-19 pandemic for a while now. For the first time in a long time, we’re paying attention to what health experts are saying. One bit of advice we’re hearing from some of them is based on research on how the indoor relative humidity affects viruses, bacteria, and other pathogens. This line of thinking goes back at least to the 1980s with a paper that introduced what has become known as the Sterling chart (below).

That’s good information to have. It’s not enough, though, because . . .

A humidifier can rot your house

Here’s the thing about water vapor and cold materials, though. They love each other! If you live in an older house in a cold climate and someone tells you to keep your indoor air at 50% relative humidity, that’s likely to cause problems.

Yes, some of that humidity will leave the house entirely and get lost to the outdoors. Some of it, however, will pass through walls with cold sheathing and studs. And there it’s likely to find cold materials and stick to them. The more water vapor you put in the indoor air, the more you may be adding to the inside of your walls.

And the more water vapor you put into those cold walls, the more likely you are to cause those walls to rot or grow mold. If you’re humidifying the air for health reasons, then, you may actually be making your indoor air quality worse, not better.

Remember that Harvard building I mentioned? It was called Werner Otto Hall and was demolished in 2008. Why? The people in charge decided, because the building housed delicate art pieces, to keep the indoor conditions at 70°F and 50% relative humidity. They also decided to keep the building under positive pressure. That meant that humid indoor air leaked outward through the walls. Long story short: They rotted the building so badly it had to be torn down after only 17 years.

Incomplete advice about indoor humidity

Controlling the indoor conditions for health is absolutely a good idea. But you’ve got to understand the big picture. A house is a system. When you make a change to one part of the system, it has impacts on other parts. That’s the case with trying to crank up your indoor humidity to keep the viruses at bay. You may be creating other problems inadvertently, which is another reminder that a house is a system. Eric Sevareid said it best:

“The chief cause of problems is solutions.”

In short, it should be OK to use a humidifier to raise the indoor humidity in a leaky house in a cold climate to 30 or 35%. Once you start getting up to 40%, though, your solution may be the cause of new, potentially bigger problems. If someone tells you the relative humidity has to be 50%, that’s bad advice. Keep in mind that it’s usually stated as a range because not every house can take 40 or 50%.

Remember that the cause of dry air in winter is air leakage, so air-sealing is the first and best way to keep your humidity from going too low. And it has the additional benefits of making your house more comfortable and less susceptible to moisture damage.

_________________________________________________________________________

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He is also writing a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

3 Comments

Alison,

“The chief cause of problems is solutions.” That's a great aphorism.

This is also very useful advice: "Keep in mind that it’s usually stated as a range because not every house can take 40 or 50%."

I wonder whether in some climates it might be a good strategy to design the building assemblies to be more capable of dealing with that mid-range indoor humidity through increased ability to dry to the outside?

I'm interested in this question also.

In my climate (coastal Northern CA), where condensation at the sheathing due to extreme cold isn't as much of a problem, we can still have high humidity even in the dry months, thanks to the fog from the Pacific. During those days/weeks that we often call "June gloom", the high/low/dewpoint temperature hover very near each other for long periods of time, and it's very misty.

That, coupled with shortsighted building regulations in the 1990s that required tighter buildings but not active ventilation resulted in a lot of humidity trapping and dry rot issues in houses from that era - which might surprise many since this is generally considered a drier climate.

My house had this exact issue and I had to replace the 12 year old roof shingles and dry rotted roof sheathing because the original attic was not vented, and there was no mechanical ventilation in the house.

When I recently did a passive-house-like remodel on the house, I discovered several other areas where sheathing had dry rotted, and as a result I was keen to use an air sealing WRB solution that could dry out and in (so no spray foam).

Hopefully those choices will hold up over time.

Dan,

I think a good starting point would be not to use what we know are risky or marginal building assemblies. The ones that get described on GBA with phrases like "this will work with very diligent air-sealing." Or "With a deep enough ventilation channel this roof should be safe". Building resiliency into a house, even at the expense of some energy efficiency, makes sense to me.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in