In March, 2017, I visited the Shacklands Brew Pub in a shabby industrial part of Toronto to hear a presentation, “The Carbon Elephant in the Room” by Chris Magwood, then the director of the Endeavour Centre in Peterborough, Ontario. I knew of Chris from his work with straw-bale construction and had visited “Canada’s greenest home” in Peterborough, covered on Green Building Advisor in 2013. I had also been writing about embodied energy, as it was then called, for about five years, so I thought it might be an interesting talk.

Changing times, new information

What I saw in that lecture changed my life. The slide below showed how a high-performance build insulated with polyurethane foam and heated with gas still had significantly higher carbon emissions than one built to the not-very-rigorous Ontario Building Code because of the “embodied carbon,” or the carbon emissions released upfront during construction. Almost everything we had been doing was wrong; almost everything I was writing had been wrong; it was an entirely new way of looking at the world of carbon and construction. Or as I wrote later in my book on the topic, “When you look at the world through the lens of upfront carbon, everything changes.”

And indeed, in the last eight years, much has changed. Foams have been reformulated, but some builders and designers have moved on from them to less carbon-intensive options. Chris went back to school and got a Master’s degree, and with Builders for Climate Action, he launched the BEAM carbon calculator.

Soon, the bigger guns south of the Canadian border caught on to Chris, and he is now manager, carbon-free buildings, at RMI, formerly the Rocky Mountain Institute. Chris, Tracy Huynh, and Victor Olgyay have written a report, The Hidden Climate Impact of Residential Construction, which is the foundational document for HomebuildersCAN, a new carbon-action network that seeks to answer the question: How can home builders take a leading role in understanding, measuring, reporting, and acting strategically to adopt and scale, profitable low embodied–carbon building practices?

Their objectives include:

- Increase performance on embodied emissions from new homes and share successes with stakeholders.

- Advocate for alignment across the sector, including regulators, ESG reports, lenders, and energy efficiency programs.

- Adopt and scale profitable climate-smart building practices.

Why rally the home building sector

HomebuildersCAN doesn’t officially launch until April, but the report is worth a serious look now. The scale of upfront emissions from the home building industry is astonishing: “New-home construction in the U.S. creates over 50 million tons of embodied carbon emissions annually, equivalent to the emissions from 138 natural gas-fired power plants or the yearly emissions from entire countries such as Norway, Peru, and Sweden.”

This seemed surprising, given the majority of North American homes are built with light-wood framing. However, the bulk of the upfront carbon is from the manufacturing of concrete, cladding, insulation, and interior surfaces, totaling 70% of the total emissions of new-home construction.

The more efficient a building becomes, the bigger proportion of life cycle emissions happen upfront. And while governments and rating systems like HERS measure energy efficiency, they ignore the upfront emissions.

“If [Cradle-to-Gate] embodied carbon emissions go unaddressed, the upfront emissions from new-home construction are likely to be the equivalent of 20 to 60 years, or even more, of accumulated operational greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The embodied carbon emissions are in the atmosphere and irretrievable from the day the new home is occupied, whereas the operational GHG emissions accumulate over time.”

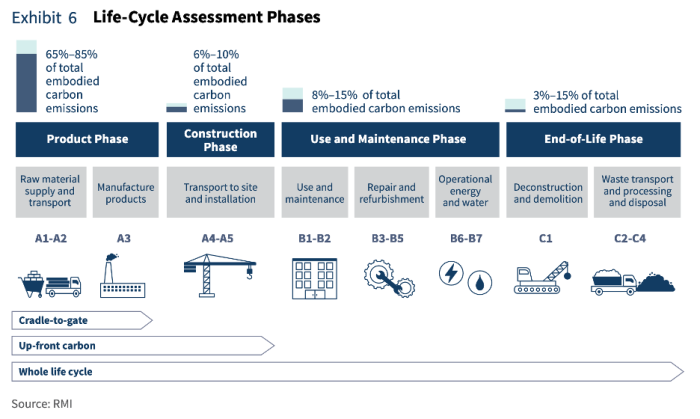

I should note that the report uses “CtG” or Cradle-to-Gate emissions, which refers to product phases A1 to A3, whereas I have been using the term “upfront carbon,” which includes the construction phases A4-A5, and which is common in the industry. This has long been a bit of a bone of contention between Chris and me; he claims that A4 and A5 don’t amount to more than 5% to 10% of total life-cycle emissions, and the numbers are wildly variable and difficult to calculate. They reiterate this in the report, noting that “A (transportation to site) emissions are estimated in some Life Cycle Assessments (LCA) by identifying manufacturing locations and calculating distances to the construction site. However, the complex supply chains common in new-home construction can often render basic assumptions incorrect.”

A recent report in BuildingGreen, The Missing Embodied Carbon Link: Construction, concluded that construction emissions could be as much as 30% of the project’s embodied carbon. I asked Chris about this, and he gave a long and detailed answer, the gist of which is:

“My opinion on the scale of these emissions is definitely changing. I had built my assumptions from reading many of the same studies quoted in the article—me and everyone else thinking about embodied carbon, it seems! I think that in my niche field of low- and mid-rise residential construction, it may still be the case that on-site construction emissions aren’t that high. We just don’t excavate so deeply or require cranes or many of the other fuel-intensive operations that happen on large construction sites. However, there is likely a higher proportion of guys driving around in big trucks to pick up another box of nails…”

“…The retail suppliers for residential projects have really complicated and shifted supply chains. I once tried to trace the path that my bag of Roxul in Peterborough took to arrive from the factory in Milton, only to find out that it came from West Virginia, via a path that took it through three different logistics hubs! Until the bar code on products enables such tracing, transportation of goods to site is always going to be a bit of a wild estimate.”

In the end, Chris is persuasive, noting responsible builders know what to do: “drive less, use electric vehicles and equipment, don’t burn fossil fuels on-site, buy more local materials, don’t dig giant holes in the ground, etc. Actual calculations will bear these out, but do the calculations teach us anything we didn’t already know?”

There are easy-to-calculate things that can be done in the Cradle-to-Gate phases. Switching from fiberglass to cellulose, brick to wood, or tiling to linoleum can drop CtG emissions by 50%. (Whether the market could supply a large-scale switch to cellulose in a world without newspapers is another problem).

The report concludes by noting that this issue is critically important and that including CtG embodied carbon emissions should be a central consideration for the decarbonization of new homes. Developers and builders should use the tools that now exist (like the BEAM calculator), and efforts should be coordinated to implement and regulate reductions.

“Efforts to address energy efficiency in new homes are currently developed within many different standards and programs. Home builders and buyers are faced with a variety of scores, ratings, and systems, leading to market confusion and diffusion. Efforts to implement programs and regulations for embodied carbon are in the early stages, offering a unique opportunity to coordinate efforts to ensure that the market receives clear and consistent signals about how embodied carbon will be measured.”

This is the purpose of the HomebuildersCAN initiative launching in April.

Single-family home footnote

Perhaps the most interesting table in the report got very little discussion other than a sentence in the conclusion: “In addition to material substitutions, designers can deploy more material-efficient actions, such as simplifying forms, minimizing below-grade space, minimizing uninhabitable floor area, reducing or eliminating concrete floor slabs, and considering multi-unit homes that require less overall insulation and use structural systems more efficiently.”

In fact, the numbers in this table are stunning: the emissions of a single-detached home are many times greater than those of any other housing type. If you measure emissions intensity in kilograms of CO2 per bedroom, they are 4.45 times as high in a single detached house than they are in a duplex with a suite. It’s apparent from this chart that what we build has far more impact than what we build it out of. It almost seemed that this was buried, and Chris explains:

“The typology piece is one that I think is incredibly important but hasn’t made it to the top of the list of discussion points from any of the studies, despite our efforts to include it. There weren’t a lot of duplexes in the study, but what we examined landed right in between the singles and the towns… making it look like there’s a pretty direct correlation to embodied carbon and number of units in a building. My guess is that this holds true until reaching the tipping point where buildings get large enough that they start needing lots of concrete and/or steel as well as elevators, etc. Another strong argument for the missing middle!”

This is perhaps too much to ask of the industry in one shot, but the numbers are clear: If we are serious about reducing carbon emissions, both upfront and operating, we need to rethink our North American obsession with single-family dwellings.

Attend the webinar launch of HomebuildersCAN on April 3, 2024.

________________________________________________________________________

Lloyd Alter is a former architect and developer. His journalism career includes 15-plus years as design editor at Treehugger.com. Today he teaches sustainable design at Toronto Metropolitan University. His work can be found at Carbon Upfront. Images courtesy RMI, except where noted.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in