Imagine your car’s engine only had one speed. To go somewhere, you’d start the engine, and then it would run at its maximum rpm until you wanted to slow down or stop. Then you’d turn off the engine to coast or brake. I think you’d agree this kind of car would be difficult to control and would make for a pretty rough ride. What’s confusing to me is that most central heating and cooling systems in this country work almost exactly that way. When your thermostat calls for heating or cooling, your HVAC equipment goes full tilt until the set point is reached and then it shuts off, waiting for the next call from the thermostat.

On top of this, heating and cooling equipment is sized so it can keep the house warm or cool in the coldest or hottest periods, which is often only a few days or weeks a year. The result is a noisy HVAC system that in most conditions only runs for a few minutes at a time, making it difficult to maintain an even temperature and control humidity. Adding insult to injury, American HVAC systems are routinely two or three times bigger than load calculations call for, making the inherent comfort problems of on/off operation even worse.

But there is a solution. It’s described as variable capacity, which means the HVAC appliance’s output is matched to the heating or cooling load automatically, contrasting with the on/off operation of single-stage and to a lesser extent two-stage equipment (which has two operating speeds). With variable-capacity heat pumps or air conditioners, the equipment’s compressor runs at a slower speed for a longer time, which provides quieter operation, better humidity control, and greater efficiency.

Variable-capacity modulating boilers are well-known by plumbers and HVAC techs in heating climates, and ducted and ductless minisplits (see “Making Sense of Minisplits,” FHB #296), which are also variable-capacity systems, have become ubiquitous in both heating and cooling climates. But variable-capacity central equipment, which has been around for a decade now, is lesser known.

If you want one of these systems, you’ll have to do your homework, because HVAC contractors and manufactures sell a lot more entry- and mid-level heating and cooling equipment, which seems to be their focus. According to a 2021 J.D. Power report on HVAC equipment, variable-capacity central equipment represents only about 5% of central HVAC equipment sales, so if you want better HVAC gear for your or your client’s house, this article is a good place to start.

HVAC terms to know

Understanding heating, cooling, and ventilation strategies involves industryspecific lingo. Specs among variable-capacity heat pumps and air conditioners vary widely. Understanding their differences starts with understanding the terms that describe their performance.

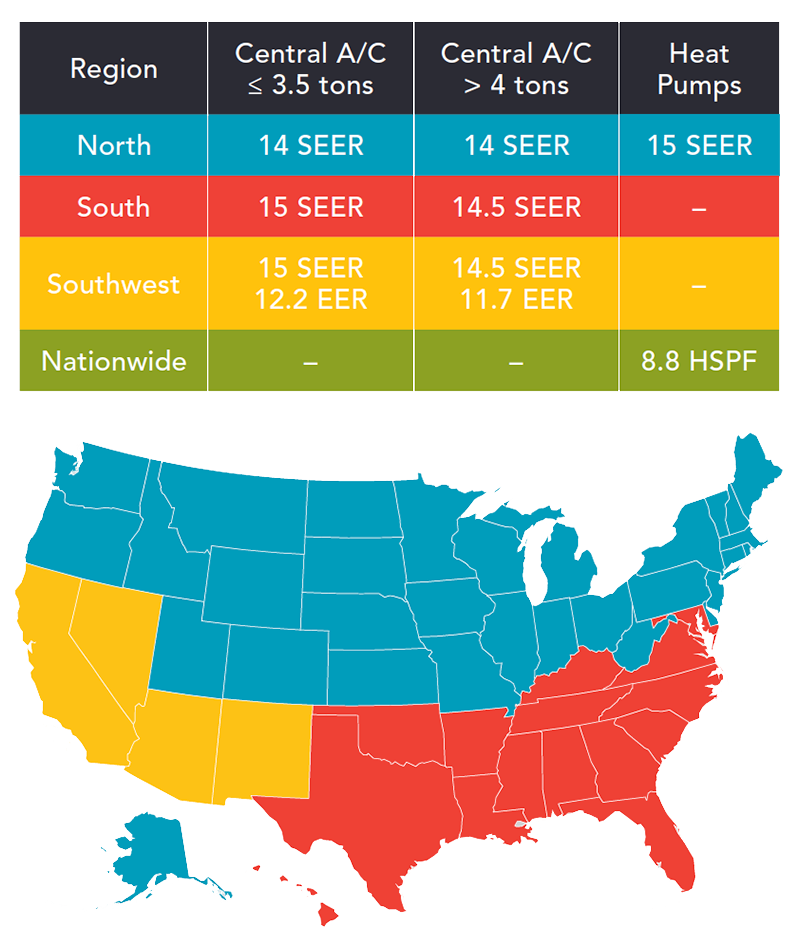

SEER, or seasonal energy-efficiency ratio, describes the cooling efficiency of central air conditioners and heat pumps in cooling mode. Higher numbers mean greater efficiency.

EER, or energy-efficiency ratio, compares the Btu per hour of cooling to the amount of electricity used to produce it. Higher numbers mean greater efficiency.

HSPF, or heating seasonal performance factor, describes a heat pump’s overall heating efficiency taking into account defrost cycles and the need for supplemental heat. Higher numbers mean greater efficiency.

Turn-down is defined inconsistently, but refers to the minimum capacity of a variablecapacity heating or cooling appliance. Variable-capacity central equipment turndown is generally between 30% and 70% of the equipment’s maximum output.

Sensible cooling is the load associated with making the building a comfortable temperature. Solar gain, heat generated from appliances, and air leakage are only a few of the factors affecting it.

Latent cooling is the load associated with dehumidification and the energy consumed in removing it from the air and waterabsorbing materials in the building and home furnishings.

Manual J is the Air Conditioning Contractors of America (ACCA) heat gain and loss calculation to determine the loads in a building. A building’s size, airtightness, insulation, and glazing are a few of the considerations.

Manual D is the ACCA method for calculating register number and sizes, duct layout and design, and airflow per room.

Short-cycling is when heating and cooling equipment runs for short periods of time, which hampers efficiency, reduces comfort, and reduces equipment life.

Commissioning is the setup of a new system, including adjusting blower speed, air delivery, and any other aspects of operation for maximum efficiency and comfort.

How variable capacity works

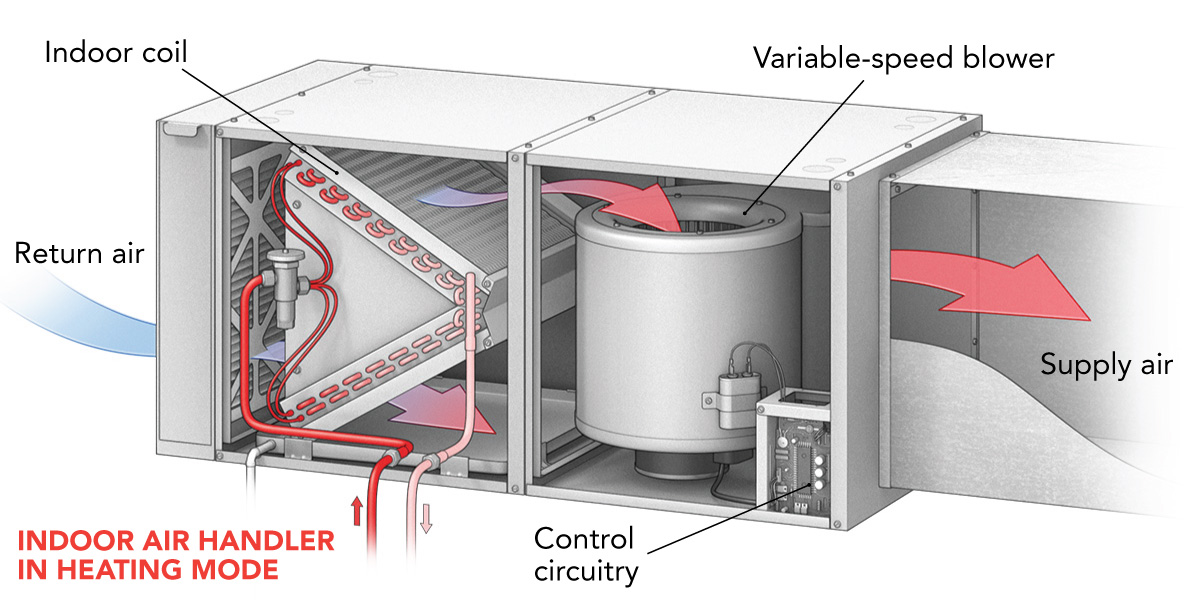

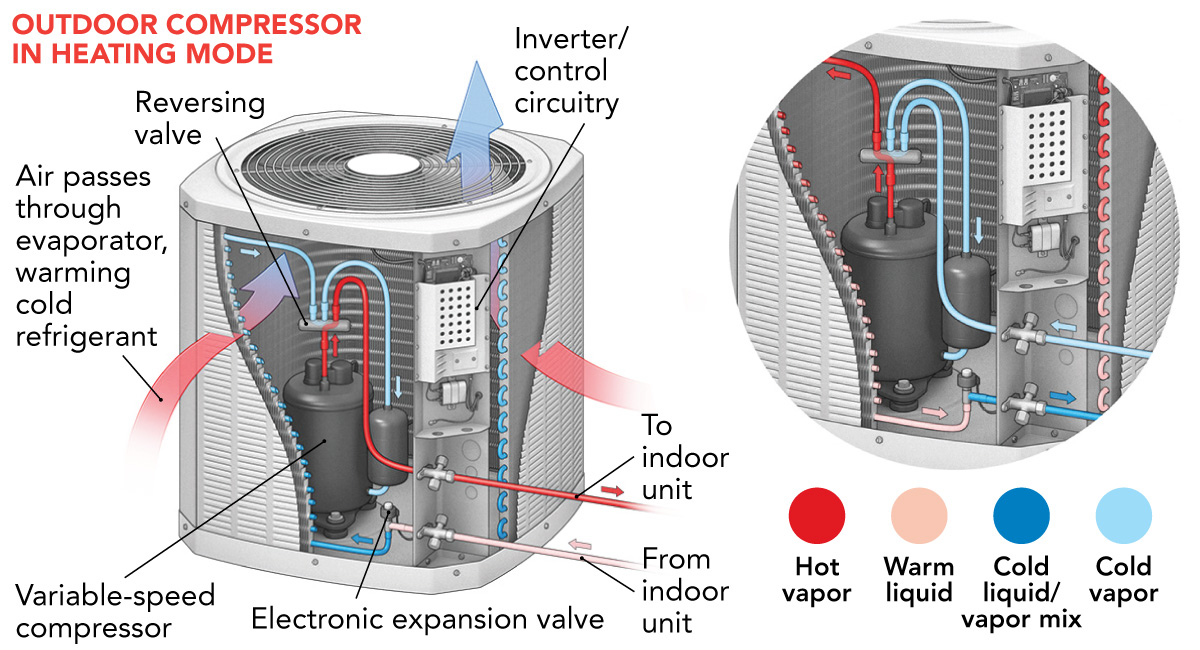

The secret behind variable-capacity central heat pumps and air conditioners is the inverter-controlled compressor that

can ramp up or slow down based on the heating or cooling load. The compressor is paired with a furnace or air handler equipped with a variable-speed blower and computer circuitry that work in tandem with the compressor to match the loads. Some systems use conventional thermostats; moresophisticated systems often use proprietary controls.

The advantages of variable capacity

As I mentioned earlier, common HVAC equipment is sized so it can handle the loads on the hottest or coldest days of the year. (When you add in safety factor and conservative load calculations, equipment is often sized at 20% to 30% over the peak load.) The rest of the season, it runs for a few minutes and then shuts off. Variable-capacity equipment has a compressor and control circuitry that can slow down the refrigeration cycle, so it runs for a longer time. (For this reason, these systems are also described as variable-speed.) The big difference among variable-capacity equipment is the “turn-down ratio,” which is how much the system can throttle back. The most sophisticated variable-capacity central equipment can turn down to about 20% of its maximum capacity to better match the heating or cooling loads. Less-desirable equipment may turn down to as little as 70%. For comparison, some minisplits operate at less than 9% of their maximum capacity in low-load conditions. Turn-down means variable-capacity systems can offer the following advantages:

Better humidity control. If you’ve ever been in a building that feels cold and clammy on summer days, you’re experiencing overcooling without effective humidity control. This is a result of the conventional equipment running a short time and then shutting off, a condition known as short-cycling. Variable-capacity systems allow the equipment to run longer for better dehumidification.

Quieter operation. Inside, the system is running at a lower speed, so there’s no woosh of air rushing through the registers. The outdoor unit is quieter because it’s running slower too. Eric DeLuca, director of green building for Massey Berg LLC, a residential builder and remodeler in Minneapolis, has been enjoying his Bryant variable-capacity heat pump for more than a year now. He put it this way: “It’s so quiet, I often can’t tell it’s running until I put my hand above the outdoor unit and feel the hot air blowing out. When my neighbor’s single-speed air conditioner roars on, I can hear it from inside my house.”

Better filtration. With a conventional system, the air is only filtered when the system is running, which in shoulder seasons may be a few minutes an hour or less. A variable-capacity system runs for much longer periods, so it’s filtering a greater percentage of the time.

Lasts longer. The longer lifespan of variable-speed equipment was explained to me by P.E. Mark Jussaume, whose day job is running the Boston office of SmithGroup, a 1200-employee architectural and engineering firm that specializes in the construction and renovation of buildings and outdoor spaces for government, medicine, and education. In 2019 he built his own high-performance house and wanted a similarly high-performance HVAC system.

Mark told me that the variable-speed compressor and ECM (electronically commutated) blower on his Lennox gas furnace and XC25 air conditioner not only make his house quiet and comfortable, they should last longer than single-speed compressors and blowers. “Every time you start an electric motor you’re wearing it out, so when you’re running the system for long periods without constant starts and stops, it’s easier on the components and they last longer,” he said.

Reduced energy consumption—In a variable-speed system, fans and compressors run at reduced capacity for most of the year. A 20% reduction in speed results in a 50% reduction in energy consumption. According to Mark, his electric bill has been reduced by 30% due to his system’s ability to match the capacity to the load.

Why are these modern HVAC systems more efficient?

The big difference among variable-capacity HVAC equipment is the “turn-down ratio,” which is how much the system can throttle back. The most sophisticated variable-capacity central equipment can turn down to about 20% of its maximum capacity to better match the heating or cooling loads. Less-desirable equipment may turn down to as little as 70%. For comparison, some minisplits operate at less than 9% of their maximum capacity in low-load conditions. Turn-down means variable-capacity systems can offer the following advantages:

Better humidity control—If you’ve ever been in a building that feels cold and clammy on summer days, you’re experiencing overcooling without effective humidity control. This is a result of the conventional equipment running a short time and then shutting off, a condition known as short-cycling. Variable-capacity systems allow the equipment to run longer for better dehumidification.

What’s on the market?

Variable-capacity heat pumps and air-conditioners are available from all major heating and cooling equipment manufacturers. Typically only their higherend equipment is variable-capacity. In addition to providing greater comfort and efficiency, these appliances are quieter and have more features than mid-tier and entry-level equipment. Heat pumps, which heat and cool, are used in the middle and southern parts of the U.S., where subzero temperatures are rare. In northern climates, a variable-capacity air conditioner, which only cools, is usually paired with a gas-or propane-fueled forced-air furnace with a variable-speed blower, because central heat pumps stop making adequate heat at about 5°F.

Carrier Infinity 24 Heat Pump

Cooling SEER Up to 24 Cooling EER Up to 16

Heating HSPF Up to 13 Noise level 51 db

Lennox XC25 Air Conditioner

Cooling SEER Up to 26

Cooling EER Up to 15.5

Noise level 59 db

Allied Air Products Lynx Heat Pump

Cooling SEER Up to 18 Cooling EER Up to 11

Heating HSPF Up to 10 Noise level 60 db

Rheem RP 20 Heat Pump

Cooling SEER Up to 20 Cooling EER Up to 14

Heating HSPF Up to 11.5 Noise level 59 db

Trane XV20i Air Conditioner

Cooling SEER Up to 21 Cooling EER Up to 14

Noise level 43 db

Hi-tech HVAC for the rest of us

There’s a perception that variable-capacity equipment is the exclusive domain of high-end HVAC equipment, but that’s changing; you can often find variable-speed mid-tier equipment too. Cameron Prince, an engineer and product manager for Allied Air Enterprises, makers of Concord, Ducane, and Allied HVAC equipment, told me that they recently released their Lynx line of variable-capacity 18-SEER heat pumps and air conditioners. This equipment, which has all the advantages of more-expensive central equipment, uses mainstream 24v thermostats, which many people prefer to the sophisticated touchpads that advanced systems are often paired with.

Some homeowners want to control and monitor their system from their smartphone or tablet. If you want this capability, make sure the system you’re considering is compatible. I asked Eric about the control app Bryant offers with their system. He said the original version was clunky and hard to figure out, but the recent version is more functional.

Even the more affordable offerings in the variable-capacity segment are built better than the “builder boxes,” as entry-level equipment is sometimes derisively described. Outdoor units generally have additional sound insulation and the cabinets are more rust-resistant. They have more sophisticated self-diagnostics for troubleshooting, and higher-end units can remind you when it’s time for filter changes and annual service. And Mark told me that in general, variable-speed equipment tends to be made of higher-quality components.

One thing to keep in mind is that while you can often replace a failed outdoor unit and leave the indoor coil in place with a conventional system, variable-capacity compressors need a compatible air handler and sometimes a proprietary thermostat. As Eric put it, “You may also need the manufacturer’s own thermostat, not a Nest.”

Help for contractors

For a couple decades now, I’ve been critical of the HVAC industry. I feel most techs and business owners are poorly trained; despite decades of appeals by engineers and building scientists to do a better job right-sizing HVAC equipment and ductwork, they still rely on rule-of-thumb sizing and often do a bad job designing and installing ducts. A variable-capacity heat pump or air-conditioning unit won’t help deeply flawed ductwork, but it can help with oversizing. Recent Facebook comments made by an anonymous Florida HVAC contractor gave me a deeper understanding of the difficulties HVAC installers face when sizing equipment.

In response to other contractors with attitudes similar to mine, he said that when he gets aggressive with Manual J calculations, equipment can end up undersized because of the building envelope, which is outside his control. This can happen when the framer leaves major air leaks that aren’t otherwise controlled or the insulation contractor misses part of the thermal boundary. On an especially hot day when the house won’t get below 80°F, the client isn’t going to call the general contractor or the insulation contractor, they’re going to call the HVAC contractor. If they can’t track down the offending envelope failure, they could be on the hook for bigger equipment to make the clients comfortable.

Variable-capacity central equipment gives contractors a cushion of extra capacity without the energy and comfort penalty of oversized conventional equipment. Recognizing this fact, manufacturers typically stick to full-ton increments of cooling for variable-capacity heat pumps and air conditioners, compared to the half-ton increments offered with single- and two-stage equipment. The variable capacity also allows contractors to match different heating and cooling loads.

In cooling climates, where the heating load may be half the cooling load, the system can match the actual loads without short-cycling. In heating climates that need less summertime cooling, variable-capacity systems can better match those lower loads too.

Some techs are resistant

Despite the advantages of variable-capacity equipment, you may have to interview a slew of prospective HVAC contractors to find one willing to step outside their comfort zone and install one of these systems. Mark and Eric told me that they went through a list of HVAC contractors before they found someone interested in installing the equipment they wanted. HVAC contractors are often hesitant to offer it. Cameron had the best explanation as to why that I’ve heard yet: “Since the beginning of air conditioning in the ’50s, the equipment has always been single stage, so it’s what contractors are familiar with, and in fairness to them it’s simple, reliable, and inexpensive.”

There’s also hesitation by some homeowners who may worry about the added complexity of these systems. In a switch from fossil fuels to a renewable-energy grid, heat pumps are part of the solution, and technological improvements make them practical for all but the coldest parts of the United States—but old perceptions persist. Eric told me that the contractor who installed his system was forced to deactivate the heating function on another customer’s variable-capacity central heat pump, because they “didn’t want to heat their house with an air conditioner.”

One of the things it’s smart to discuss with a potential HVAC dealer is the availability of spare parts for a variable-capacity system. The components inside one and two-stage central equipment in the entry and middle levels is pretty universal and spare parts are easy to find. When you move to variable-capacity systems, the components are more proprietary and parts can take longer to get, which can be a real problem during a heat wave or cold snap.

Phillip Oglesby, who’s in charge of training and customer education at Rheem, says that once HVAC techs have one or two variable-capacity installations under their belt, he expects they’ll find the technology way less scary. He says his company has been working hard to train its dealers on the advantages of variable-capacity systems, offering in-person and online training. I think as more contractors

get comfortable with the equipment, we’ll see it more and more.

________________________________________________________________________

Patrick McCombe is a senior editor at Fine Homebuilding magazine. Photos courtesy of manufacturers, except where noted; illustrations by Christopher Mills. This article first appeared in Fine Homebuilding magazine issue 302.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

12 Comments

Going along with the initial statement comparing to a car - maybe the HVAC industry is going through what the car industry hit in the 70s. Muscle cars weren't as popular as the efficient Japanese cars of the time during a gas crisis. You can find relics of the companies who weren't able to adapt at your local Cars and Coffee. We can't keep producing the same old tech as standard equipment and expect people to continue to buy it. Everything mentioned in this article seems like it's standard tech that's in 10+ year old Japanese heat pumps. It's really not high tech, it should be standard for all companies at this point except some real bottom shelf stuff. If the American companies want to treat it as high tech only, they may get run out of business as the market shifts to demanding more tech.

"In northern climates, a variable-capacity air conditioner, which only cools, is usually paired with a gas-or propane-fueled forced-air furnace with a variable-speed blower, because central heat pumps stop making adequate heat at about 5°F.:

Is this true? Because posters here on GBA regularly suggest that ducted heat pumps are the best option when looking to retrofit with mini splits.

This article is confusing for someone who has read much more about heat pumps than other 'central systems.' The frame of reference appears to be quite different. For example, people here often ask about adding heat pumps to their house, and the question comes up: ducted or ductless. This article assumes people are seeking central equipment and the question is modulating or not but may not even be a heat pump. Why should one carry one assumption vs the other?

It’s a pretty confusing article with some repetition. An important bit of context is that most all Americans have ductwork - and most have AC too. So the case seems to be that variable speed is best and a heat pump is cheap when compared to a similar AC. I think the article is written for the majority, not the Northeastern US reader who might be using hydronic heat with little or no AC.

The 5 degrees number is flat out wrong - but most people aren’t installing Mitsubishis either so once again it’s written for the majority. I also have no issue pairing a furnace with an heat pump if a homeowner, or even more likely, a contractor needs that reassurance.

"I think the article is written for the majority, not the Northeastern US reader who might be using hydronic heat with little or no AC."

That probably explains why something about the article just felt odd, being a northeasterner. I'm still perplexed by the ubiquitousness of central AC in so much of the country. Though I think many northeasterners are now trying to figure out how to integrate efficient and effective AC systems in their existing homes.

Ir also explains why electricity is so cheap outside of the northeast!

Because people outside the northeast use more of it?

I'm confused. I see the claim here of better humidity control, yet when I look at published sensible heat ratios for some variable capacity heat pumps, I see SHR numbers much higher than older, single speed systems. Somebody please explain the contradiction.

Lower SHR = less change in temperature and more humidity removed. It takes about 15 minutes or so for an air conditioner or heat pump to start sending water down the drain, so longer cycles remove more humidity. Our Bryant Evolution AC and gas furnace can turn down to ~40% of their full capacity, which results in much longer cycles. To tell whether the furnace/AC is running, I often have to put my hand up to a register. (Or, I can view "equipment operating status" on Bryant's proprietary thermostat to tell what's running.) No endorsement of Carrier/Bryant over other brands implied.

Jonathan, I understand that longer cycles, and slower airflow, remove more humidity. What I don't understand is why the published SHR of some variable speed systems is so high. I saw one SHR listed as 0.95! Some old, ordinary single speed systems can do 0.7.

Hi All, Yes the article is intended for the majority of the US where central ducted systems are the norm. That's central heat pumps for mixed and cooling climates and gas furnaces paired with central AC in the Midwest and Upper Midwest, generally speaking. My intention was to focus on the availability of better equipment than what folks are used to seeing.

Patrick: Yes, some HVAC contractors are uncomfortable with more complicated systems, but manufacturers offer training. And, energy efficiency programs and tax credits can help transform the market.

Also, the text below is repeated twice in your article - (a common editing hazard). You might want to edit out the repetition?

"The big difference among variable-capacity equipment is the “turn-down ratio,” which is how much the system can throttle back. The most sophisticated variable-capacity central equipment can turn down to about 20% of its maximum capacity to better match the heating or cooling loads. Less-desirable equipment may turn down to as little as 70%. For comparison, some minisplits operate at less than 9% of their maximum capacity in low-load conditions. Turn-down means variable-capacity systems can offer the following advantages:

Better humidity control. If you’ve ever been in a building that feels cold and clammy on summer days, you’re experiencing overcooling without effective humidity control. This is a result of the conventional equipment running a short time and then shutting off, a condition known as short-cycling. Variable-capacity systems allow the equipment to run longer for better dehumidification."

Wonderful concept if reliable.. But word is you better have a whole house surge protector AND another one on the unit. Replacing one of those boards is expensive and it happens more often than multi speed boards..

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in