If you are designing or building a high-performance home, you probably know that a minisplit heat pump is an efficient, affordable way to provide space heating and cooling. Unfortunately, in spite of the fact that the technology isn’t particularly new, many American HVAC contractors are still unfamiliar with minisplit heat pumps — so you may not get your minisplits installed properly without providing your contractor with a little hand-holding help.

Jordan Goldman, the engineering principal at a Massachusetts company called ZeroEnergy Design, knows a lot about minisplits. At a recent conference sponsored by Taunton Press (the Fine Homebuilding Summit in Massachusetts), Goldman gave a presentation, “Making the Most of Minisplits,” that provided valuable minisplit system design and installation tips to HVAC engineers, contractors, and architects.

The broad perspective

Goldman began his presentation with a few important reminders reminiscent of the old saying “Don’t let the tail wag the dog.” Goldman advised, “The heating system is not the end goal — comfort is the goal.” He also pointed out, “The primary heating system should be the building envelope. Airtightness will keep your house comfortable. … If you have a good envelope, it doesn’t much matter if the conditioned air is delivered high or low.”

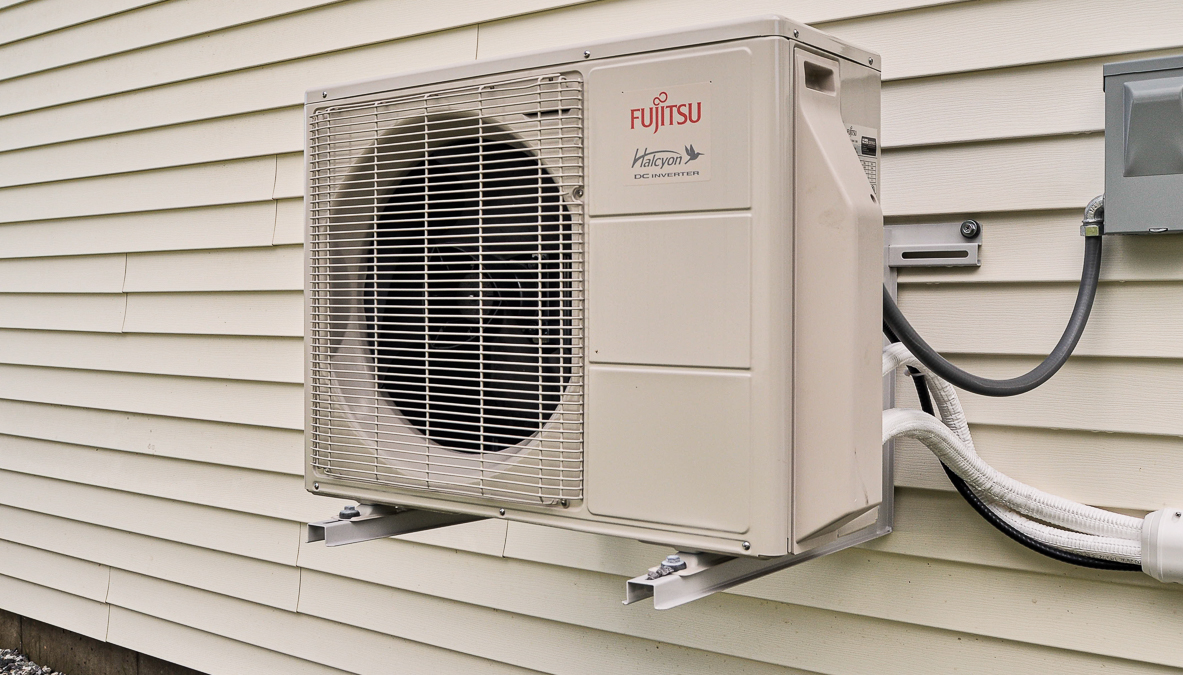

These days, environmentally conscious builders are moving away from fossil fuels — so the fact that minisplits use electricity as a fuel is an obvious advantage. Another advantage to minisplit systems, according to Goldman: “These units are properly sized for superinsulated houses. Single-zone systems are available down to 9 Kbtuh.” Goldman also noted that minisplit outdoor units are “much quieter than a conventional air conditioner.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

Goldman noted that minisplit systems also have a few disadvantages: “Their heating capacity decreases as outdoor temperature decreases; the heating efficiency decreases as outdoor air temperature decreases; and electricity is expensive relative to natural…

This article is only available to GBA Prime Members

Sign up for a free trial and get instant access to this article as well as GBA’s complete library of premium articles and construction details.

Start Free TrialAlready a member? Log in

22 Comments

Thanks Martin,

Glad to see you are enjoying your "retirement" : )

We recently had a single zone (Mitsubishi) installed where the indoor unit was on an interior wall. Every 15 minutes or so in cooling mode, it would make a very annoying mechanical sound. Turns out the installer had included a pump to evacuate condensation. They moved it closer to an exterior wall, removed the pump and allowed gravity to do the job.

In a new build we are designing (2200 sq. ft, slab on grade bungalow, most likely SIPs), we want to have an indoor unit in the centre of the house. Is there a way to avoid having a pump to remove the condensation?

Also, are you aware of any new single zone designs that are very small i.e. for bedrooms? I really like the individual control and the ability to close the bedroom door but realize the limitations of oversizing. We are in southern Ontario so zone 6 I presume. I'd like to use small Mitsubishi Hyperheats but they are probably too big for the bedrooms (approx. 200 ft.).

Thanks again.

Don

Don,

Q. "In a new build we are designing (2200 sq. ft, slab on grade bungalow, most likely SIPs), we want to have an indoor unit in the centre of the house. Is there a way to avoid having a pump to remove the condensation?"

A. That depends on the foundation details and the exterior grade around the house. If the house has a crawlspace or basement with an exposed wall, a gravity drain is possible. In your case -- a house with a slab-on-grade foundation -- you will probably need to (a) install the minisplit head on an exterior wall, or (b) install a condensate pump.

Q. "Also, are you aware of any new single zone designs that are very small i.e. for bedrooms?"

A. The answer is in the article on this page: "For the time being, the smallest available indoor wall-mounted head is rated at 6,000 BTU/h." As you probably know, 6,000 BTU/h is more than the design heat load of almost any conceivable bedroom.

For a more detailed discussion of the "what do you do about bedrooms?" question, see "Getting the Right Minisplit."

Thanks Martin,

I was hoping you may have heard of intent by manufacturers to produce bedroom size units. Perhaps the cost per unit is too high to make sense of such an approach.

Thanks for your link too but I already have read it twice : ) I was hoping to avoid the complication of duct work. Although I have not read any article that mentions it, is there not a sound travel issue in bedrooms sharing ducts?

Don

Don,

Q. "Although I have not read any article that mentions it, is there not a sound travel issue in bedrooms sharing ducts?"

A. Read the article on this page again. The article notes, “Beware of noise transfer from room to room if your system has short duct runs.”

My apologies Martin,

I'm a first time builder, albeit with some experience, and tons of research.

In our case, STC ratings matter a lot. Ergo, your answers have been very helpful. Thank you : )

Don

So I gather from this thread that there is no good solution to the bedroom problem? Oversized cassettes, or added noise/complication/ugliness from ducts?

Ryan,

Possible approaches include (a) designing a house with such a superior thermal envelope (that is, above-code levels of insulation and high-performance windows) that the bedrooms don't need an indoor head, and (b) installing a well-designed ducted system.

I'm not sure why you are assuming that all ducted systems are noisy and ugly. Having a supply register in a bedroom is accepted by most Americans, as it is the usual approach in a house with a forced-air system. I'm not aware of Americans who consider registers ugly -- although some people probably do. And ducted systems need not be noisy -- thoughtful duct design can address any potential problems with sound transmission.

Martin - Point taken regarding building so that the room stays warm/cool without it's own head, though this might not be a realistic solution in extreme climates. Most people like to sleep with their bedroom door closed and after 8 hours without any air exchange, I think you'd be hard pressed to be within several degrees of where you started.

As for the ugly-factor: I am referring to the indoor cassette unit of a mini-split (not registers/ducts) The article (correctly, in most cases) points out that most homeowners don't like the look of them, both on the inside and outside of the home.

And the noise issue is related to ducts: they are excellent conductors of noise between rooms, especially if they are short and direct. In the small home I am building now, (which is "close to" super-insulated, and >1.5 ACH50) the only way to exchange air between the climate-controlled main living area and the master bedroom would be a through-wall duct/register. There is just a 2x4 wall between the rooms. We could go up and through the ceiling, using flexible insulated duct to try and dampen noise, but it's only a 12" space and I'm inclined to leave that whole and as full of insulation as possible. I'm not sure that going through the ceiling would really change much as far as sound isolation goes anyway.

A really small, 'attractive' head unit in the bedroom really would be the best solution here, I believe. Unfortunately I don't think that exists yet.

All of our projects we've used these on have been Passive House or near passive, so great thermal envelopes. We've had some success with transfer grilles (STC rated) over bedroom doors to get some convection from the hallway-mounted minisplits, but in our Chicago climate, our ERV system always works against us; we've had better success with the transfer grilles plus a CERV (conditioning ERV) instead of a standard ERV, since it sends air at comfort temperature, and moves more air around. Still, there will be some temperature differential at closed-door bedrooms due to losses and/or solar gain. Our safety net is ducted supply to bedrooms and ductless elsewhere, which ASHPs make easy with their various available indoor configurations.

Another possible solution: air to water heat pumps feeding panel radiators (heating only), slim fan-coil panels (like mini-split heads but smaller, providing heating or cooling), or radiant floors or ceilings. You can then make each emitter as small as you want and as quiet as you want.

You also have less refrigerant and less likelihood of leakage.

Curious about the VRF systems, would that help with multisplits systems ?

Eric,

As you know, VRF stands for "variable refrigerant flow." In most cases, VRF systems are large commercial systems that have multiple indoor units connected to a single outdoor unit. So-called heat-recovery VRF systems allow some rooms in a large commercial building to receive heat while other rooms in the same building receive cooling -- an approach which is almost always undesirable for a residence.

Some manufacturers are now promoting so-called "mini VRF" equipment -- and I'm not familiar with the advantages, if any, of this approach. I welcome any comments on this topic from other GBA readers.

Good evening Martin,

Yes correct I’m talking about the residential version of VRF.

Looking at this one available in Canada : https://daikincomfort.com/go/vrvlife/

Eric,

It looks to me as if Daikin has invented an acronym (VRV, for "variable refrigerant volume") simply for marketing purposes -- as a brand for Daikin's multisplit systems.

I'm not sure that there are any technical differences in approach between multisplit systems from Daikin and multisplit systems from Mitsubishi and Fujitsu.

Jordan, I installed a hyper heat Mits unit (FH15) about 5 years ago. Soon, my wife complained about a draft coming from the unit when heat was not called for (causing her to wear a hat and scarf if she sat below the living room head. Turns out the indoor head fan still runs really, really slowly even when wall T-stat is satisfied. The Mits tech advised we could snip a connection on the head control board that would stop the unit from doing that. I had to create a special tool to reach the area on the control board...a wire cutter heated to allow the handles to be bent at a right angle to the cutter head so that it would operate with the cutters fitting behind an obstructing piece of plastic. Right on about remote (wireless) thermostats for minisplits, much better than handheld remotes. I no longer can find the email or sketch of that modification in my files.

I'm curious why you didn't provide a link to Panasonic mini-splits.

Mike,

When it comes to cold-climate air-source heat pumps, Mitsubishi and Fujitsu dominate the U.S. market. In his presentation, Jordan Goldman didn't mention Panasonic equipment.

Here is a link to installation manuals for Panasonic minisplits: Panasonic installation manuals. When it comes to Panasonic engineering data, I'm not sure where it can be found. If any GBA readers can provide a link to Panasonic engineering data, please do so.

Thanks, Martin, great to hear Jordan's experience and lessons learned. One thing I'm curious about: when I presented on this topic at the last Passive House conference, Allison Bailes was in the audience, and when I made a similar comment to Jordan's about low static not handling longer duct runs, Allison made the point that with proper duct design, you can maintain proper pressure even with low static and longer runs. Being an architect, not a ME (and not having gone back and read his series on duct design), I'm not up to speed and feel like I'm hearing competing information.

All of our houses have been all-electric with Mitsubishi heat pump systems. We just assumed a medium or high static for our longer (over 10' total) ducted runs and do the Manual D calculations using WrightSoft. We went back to an old project, put in the lower static and re-ran the Manual D, and got bigger ducts; some so big as to be problematic. So it looks feasible, but perhaps in opposition to longstanding practice. Your take?

Tom,

If you're up against static limitations on a long duct run, you need to increase the diameter of the duct or reduce the number of elbows. Those are your choices -- the rest is math.

At some point, you reach a duct size that exceeds the limitations of the space where the ducts need to fit. At that point, you need a different approach -- either a high-static air handler or a ductless indoor head, for example.

To solve the "bedroom problem", we install Cadet Register heaters in each bedroom

The first cost is almost negligible, and the operating cost is negligible if thermostats are set below the minisplit temperature.

https://www.homedepot.com/p/Cadet-Register-Multi-Watt-240-208-Volt-Fan-Forced-Wall-Heater-Assembly-Only-RM162/202863231

They can be really nice in bathrooms too.

At 18:25 in the presentation (linked in the article), Jordan Goldman describes a branch box in a multisplit system as having LEVs (linear expansion valves) that "modulate the flow of refrigerant to each of the indoor units in proportion to the demand response." This suggests a continuously variable refrigerant flow to each indoor unit that tracks load. This sounds like it contradicts Dana Dorsett's description of the operation of multisplits where indoor units do not modulate with load. If that were the case, I would have thought that LEVs would be on/off valves, which is not what Goldman describes.

So, do LEVs in fact modulate indoor units? How do LEVs interact with the variable speed outdoor compressor to control indoor zones? Do port type outdoor units also have LEVs?

There a bunch of modulating components but they don't necessarily try and load match. In cooling the compressor may run to keep the evaporator pressure at the right saturation temperature, the condenser fan to regulate the head pressure to the minimum required to get the necessary refrigerant flow, and the LEV may modulate to keep the coil temperature at the target. But the output of the system per zone is relatively constant despite all the moving pieces.

While there are some variability in multisplits. The system effectively tries to maintain the nominal design capacity. The system must respond to variances of flow and entering air temperatures, and outdoor conditions. But what it doesn't do it reduce to capacity to try and match the load of the room. It will supply a relatively constant amount of heat or cooling until the setpoint is satisfied.

Conventional single stage units still have TX valves that modulate to control refrigerant system temperatures and pressures.

Log in or become a member to post a comment.

Sign up Log in