This post originally appeared at Yale Environment 360.

Stefan Paris is a 55-year-old radiologist living in Berlin’s outer suburbs. He, his partner, and their 3-year-old daughter share a snug two-story house with a pool. The Parises, who are expecting a second child, are neither wealthy nor environmental firebrands. Yet the couple opted to spend $36,000 for a home solar system consisting of 26 solar panels, freshly installed on the roof this month, and a smart battery — about the size of a small refrigerator — parked in the cellar.

On sunny days, the photovoltaic panels supply all of the Paris household’s electricity needs and charge their hybrid car’s electric battery, too. Once these basics are covered, the rooftop-generated power feeds into the stationary battery until it’s full — primed for nighttime energy demand and cloudy days. Then, when the battery is topped off, the unit’s digital control system automatically redirects any excess energy into Berlin’s power grid, for which the Parises will be compensated by the local grid operator.

“They convinced me it would pay off in ten years,” explains Paris, referring to Enerix, a Bavaria-based retailer offering solar systems and installation services. “After that, most of our electricity won’t cost us anything.” The investment, he says, is a hedge against rising energy costs. Moreover, the unit’s smart software enables the Parises to monitor the production, consumption, and storage of electricity, as well as track in real time the feed-in of power to the grid.

The Parises are one of more than 120,000 German households and small-business owners — and an estimated 1 million people worldwide — who have dug deep into their pockets to invest in solar units with battery storage since lower-cost systems appeared on the market five years ago. “No one expected this kind of growth, so fast,” says Kai-Philipp Kairies, an expert on power generation and storage systems at the RWTH Aachen University in western Germany.

Today, one out of every two orders for rooftop solar panels in Germany is sold with a battery storage system. The home furnishing company Ikea even offers installed solar packages that include storage capacity. Battery prices have plummeted so dramatically that Germany’s development bank has now scratched the battery rebates — covering about 30% of the cost — that it offered from 2013 to 2018.

To be sure, 120,000 households and small businesses represent only a tiny fraction of Germany’s 81 million people. But analysts say this recent growth demonstrates the strong appeal of a green vision for the future: a solar array on every roof, an electric vehicle in every garage, and a battery in every basement. Analysts see the embrace of home batteries as an important step toward a future in which low-carbon economies rely on increasingly decentralized and fluctuating renewable energy supplies.

To date, electricity storage has lagged far behind advances in solar power, but as batteries become cheaper and more powerful, they will increasingly store the uneven output of wind and solar power, contributing to the kind of flexibility that a weather-dependent source will require.

A lithium-iron-phosphate battery, which allows homeowners with photovoltaic panels to store excess solar electricity for later use. [Image credit: Sonnen]

Trend revives Germany’s solar panel industry

The budding popularity of solar panel and battery systems, driven by a drop in lithium-ion battery prices, has thrown a lifeline to Germany’s moribund solar sector, which has been reeling in recent years in part because of low-cost production of solar panels in China. The progressive decline of feed-in tariffs — guaranteed remuneration for consumers supplying energy to the grid — also led to a sharp drop in solar energy deployment.

But against all odds, companies like Enerix, Sonnen, and Solarwatt have gotten back on their feet thanks to home energy storage systems. In 2012, Enerix had to shut down eight of its 15 affiliates in Germany and Austria. But since the battery boom, it has been reopening old shops and starting new ones, today boasting 54 outlets that sell panels, batteries, and energy optimization systems.

Germany now has some 44 manufacturers of home energy storage systems. Germans have installed solar-panel arrays on more than 1 million buildings, but most of them lacked storage units. Now, a growing number of those homeowners are buying batteries. German electricity storage units also are being sold in France, Great Britain, Italy, the Netherlands, and Spain, as well as Australia and South Korea.

The systems are not cheap, but they offer independence

The price tag of a home storage system depends on the size of the house or business, the owner’s energy needs, the building’s access to sun, and the quality of the panels, batteries, and management systems. For a small house with just 20 panels, one can expect to pay about $8,000 to $11,000 for the PV array and roughly the same amount for the battery and DC/AC power inverter. The largest home batteries go for around $34,000. And for an extra $500, advanced devices connect the system to household appliances and optimize energy use, as well as regulating feed-in to the grid.

With such top-of-the-line technology and lots of sunlight, an owner might save as much as 80% on electricity bills, according to Solarwatt, a Dresden-based outfit manufacturing smart tech.

But the economics of battery storage aren’t the only, or even the main, motivation of most battery system buyers, says Matthias Schulnick of Enerix Berlin. “More and more people want to be independent of the power companies and rising prices,” he says. “And they want a green footprint, to do something for the future.”

In Germany, in just a few short years, home storage units morphed from a quirky niche product for tech nerds and Green Party voters to one with enormous mainstream potential. The consulting firm McKinsey predicts that the cost of energy storage systems will fall 50% to 70% globally by 2025 “as a result of design advances, economies of scale, and streamlined processes.”

Signs of the explosion in interest are everywhere: Earlier this month, the British-Dutch oil company Royal Dutch Shell purchased Sonnen, Germany’s leading maker of home batteries. The German utility giant E.ON is a step ahead of Shell, having teamed up with Solarwatt in 2016 to sell combined solar-and-battery units.

The Energy Storage Association, a U.S.-based trade group, projects that energy storage capacity will soar eight-fold from 2015 to 2020, becoming a $2.5 billion market. Bloomberg New Energy Finance projects that within 20 years the global energy storage market, of which home storage is just one part, will have attracted $620 billion in investment.

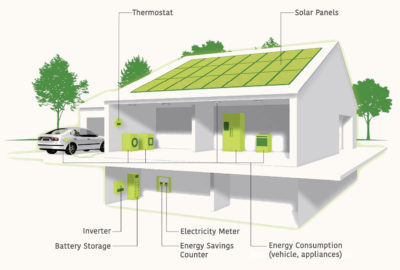

With smart home energy systems, energy generated by solar panels is stored in batteries and used to power appliances and charge electric vehicles. [Image credit: Enerix]

In California, as of 2020 all newly constructed residential buildings must be outfitted with solar panels. The owners of these buildings will surely be giving battery systems a hard look as prices fall. Adding home batteries becomes especially attractive for consumers who own electric vehicles.

The downside of the battery bonus, explains Kairies, is that “under today’s conditions it takes about a decade to pay off the battery from savings on energy bills. But most of the lifespans of these batteries today aren’t much more than 10 years, at most 15 years. Then you have to buy a new one.”

Big advances in battery performance

The boom-in-progress is in large part a consequence of spectacular advances in the performance of lithium-ion batteries — the standard type of battery found in most electric vehicles and cell phones. In laboratory conditions, technicians — who were working on improving electric vehicle batteries, not home storage units — increased the lithium-ion battery’s density by tweaking the conductors and the chemicals, which doubled storage capacity. This sent the price of storage, measured per watt hour, plummeting by half. Solar panels, too, are cheaper than ever before, although their decades-long price decline has leveled off.

Experts differ widely on the future of battery-based storage technologies and the implications for decentralized energy generation. Some, like Julia Poliscanova of the Brussels-based watchdog group Transport and Environment, argue that lithium-ion will remain the go-to battery type for the foreseeable future. The emergence of recycled EV batteries, which have too little capacity for cars but enough for household needs, would drive down costs even farther while giving lithium-ion batteries second and third lives, she says.

Others, like Stefano Passerini, director of the Helmholtz Institute in Ulm, a battery research center in Germany, says the next generation of small-scale storage will be sodium-ion batteries, which, unlike lithium batteries, don’t require cobalt, a mined chemical element that is ever-harder to find.

“Since home batteries can be larger than EV batteries, we should conserve the cobalt that’s available for cars, and go a different way with home storage,” he says. The clean-energy pioneer EWS Schönau is developing environmentally friendly batteries, such as largely recyclable saltwater batteries that contain neither carcinogenic heavy metals nor scarce minerals.

Regardless of the type of battery, home energy storage units can help smooth out fluctuations in electricity production, a function known as “balancing.” When the grid is flush with power, for example, grid operators can pay battery owners — even ones with no solar array attached to them — to store the excess for them. When the grid needs power, home and car batteries can feed energy into the grid. Experts say balancing is critical to the larger project of a low-carbon world.

But this scenario is still largely in the future. “What we have now [in home storage] certainly helps,” says Passerini, “But it’s still very little.” He says the next step is enabling home energy producers to sell to neighbors and tenants, a service known as peer-to-peer electricity trading. This would allow consumers without access to home-generated power to take advantage of the clean energy of those who produce more than they need.

Volker Quaschning, a professor of renewable energy systems at the University of Applied Sciences in Berlin, put the scale of the challenge in perspective: “We have over 100,000 home-generation and storage systems [in Germany], but in order to hit the Paris goals we need 10 million in Germany alone. There’s huge potential, but it has to be cheaper and easier.” He says that requires eliminating energy-consumption taxes on households and businesses that generate electricity for their own use and maintaining solar energy’s guaranteed tariffs, which encourage investment.

“Home storage can be expanded the same way we did solar power,” says Quaschning, referring to investment and production incentives, “which eventually created economies of scale and brought prices way down.”

It worked once, he says, and it can work again.

Paul Hockenos is a Berlin-based writer whose work has appeared in a number of publications.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

17 Comments

Why is it no one is talking about the ugly truth is the batteries don't last very long. Hybrid and EV cars at 5 years old are seeing a considerable decrease in capacity.

>"Why is it no one is talking about the ugly truth is the batteries don't last very long."

Maybe because it isn't actually true.

>"Hybrid and EV cars at 5 years old are seeing a considerable decrease in capacity."

Data? Source?

Also what relevance to EV batteries have to the discussion of a home battery? The number of ways a home battery is NOT an EV or hybrid battery are many. We're talking at least apples and pears, if not oranges.

On the end use side of the equation, the amount of current it takes to go from 0-30mph at a reasonable acceleration rate is considerably higher than what a typical German household's peak current draw would be. A lithium ion battery that is no longer able to take the Tesla from 0-60 mph in 3 seconds could easily have another decade of "second life" as a home battery or grid battery. The number of deep discharge cycles an EV battery (and particularly a hybrid battery) sees per year is at least an order of magnitude of what would happen with a typical home battery + PV setup, where the cycles are shallower & slower, with few peak amperage draws.

On the battery chemistry side they're different too. EV batteries are constrained by the weight factor, and can't use longer life chemistries that can be employed in a home battery. While Tesla's EV batteries, grid batteries, and home batteries are all built around the same technology, there is no reason (other than manufacturing scale) why they would or should be going forward.

Another significant difference between home use and EVs is the environmental temperature at which the battery is being used/stored. A typical basement will stay between 15-20C year round, which is pretty nice to the battery. Compare that to an EV battery that's hitting 40C in normal use even in not-so-hot days 50C during hot weather, and may be pushed to deliver max current multiple times before it warms up on a cool New England morning at -15C or colder. (If your house gets anywhere near that cold or hot on a regular basis you have bigger problems than battery life.)

Then there is the issue of replacement cost at 5 years or 10 years. At the double-digit learning curve of lithium ion batteries the cost of a new 5kw home battery today would have been at least 5x that amount 5 years ago, and more than 10x ten years ago. As the volumes ramp up there it's likely that in 5 years (if is should fail early) and the high likelihood of continuing the learning curve a replacement then would cost less than 20% of what replacing it next week would cost, and in 10 years even less.

FWIW: Most of those early Prius NiMH hybrid batteries that were only warranteed for 100,000 miles are still on the road well beyond 200,000 miles. And in many ways they are LESS reliable than current lithium ion EV batteries. Anecdotally, the battery in my slowly rusting Prius has 240K miles & 15 years on it, and it still beats the EPA fuel economy numbers. If it's capacity has slipped it hasn't been apparent in it's useful function, though I'm sure it would be measurable in a bench test at maximum current after that many cycles. There is a secondary market for rebuilders of vintage Prius batteries where they swap out the weakest cells in a "dead" battery with cells culled from other "dead" batteries that somewhat match the characteristics of the other cells in the battery under repair. The rebuilt batteries typically com with a 50,000 mile/5 year warranty. Street pricing is typically under a grand.

Dana,

I don't agree with this assertion:

"...the high likelihood of continuing the learning curve..."

As the battery technology matures, the amount of efficiency you can extract through the manufacturing process diminishes. The cost of the materials is unlikely to go down. And from what I've read, they're already close to hitting the wall in terms of energy density (actual vs theoretical maximum). For these reasons I don't think it's reasonable to assume we will see the same price reduction 5 or 10 years from now as we did comparing 5 or 10 years ago to now. It's possible we're still on the steep part of that curve, but I don't think it's highly likely. I think it's more likely we're nearing a tapering off.

Hopefully one of the plethora of new breakthrough battery technologies that are in the works comes to fruition and that "learning curve" can start all over again. Until that happens I'm with you, in that the farther down the curve we go the higher we have to reach for "low hanging" fruit.

Quite ignorant statement.

There are now hundreds of Tesla Taxi's with well over 200k miles and over 4 or 5 years of age and less than 10% degradation. They are still in service (I was in a 4.5 year old Model S taxi in Amsterdam last week) and doing well.

My Model S is over 5 years old and about 4% battery degradation.

My 4 1/2 Y.O. Tesla with 80k miles on it had lost about 7% of its capacity (max range went from 263 to 245) which was still about 100 miles more range than needed for 99% of my driving. Now if only the batteries in my iPhones held up as well.

If you simply stopped driving it in "Ludicrous" mode all the time the creeping range loss would slow down considerably! What ever are you going to do when it deteriorates to the point that it takes fully FOUR seconds from zero to sixty and the displayed max range drops to 225 miles? :-)

Fast charging also takes a toll, especially when it's really cold or really hot out. (Tesla probably does better thermal management to protect the battery in those situations than some other EVs.)

In Europe Nissan is already marketing grid battery packs from "second life" retired Leaf batteries. They are also doing 2 way power flows from smart car-chargers, where EV owners get paid for the ancillary grid services provided. The comparatively light and shallow charging/discharging cycles when used as a grid battery there is almost zero impact on battery longevity relative to it's primary use as an EV battery.

Somehow I think the "... ugly truth..." is that home batteries will last longer than EV batteries, and that EV batteries really do last long enough, long enough that the replacement costs at end of useful life in an EV will be pretty reasonable compared to what replacement cost would be if it needed to be done next Tuesday. Double digit percentage learning curves on technology like batteries & PV is highly deflationary.

That Tesla did not have Ludicrous mode, but I did do quite a few 4 second 0-60's during the first year of ownership.

Tesla warns about too much supercharging or constantly charing the battery to full capacity but I recall there was a Vegas to LA shuttle service using a Model S that at the time still qualified for free surcharging and after 200,000 miles the battery had only lost about 10% of its range.

The comment “After that, most of our electricity won’t cost us anything.” pre-supposes that in Germany they have no fixed line charges. Here in NZ, to be grid tied will cost around $60 per month for line and other fixed charges.

Also, as covered off by other topics on this site, no consideration in this article is given to how the consumer supplies the grid, and whether or not the grid can draw down off the battery during peak loads. The more consumers that move to this type of system, the more problems the grid operators will have regulating the supply during light load periods.

Home batteries will always be a niche product. If you have a reliable grid where you live there is very little upside to buying them. You won't get any real return on the investment until the grid goes down. It doesn't work like grid tied solar panels where you get credit for the offset in electricity you use. Because there isn't the technology (yet) to use batteries to time shift your use of electricity to a cheaper time there just isn't a good way to get a similar benefit as grid tied solar panels would provide. The other problem, as has been said, is they wear out and are expensive to replace. Ten years life is probably the maximum warranty that can be provided with a few getting to 15.

Lithium ion batteries have much better characteristics than lead acid and some types can be drawn down almost to zero without degrading much. That is much better than lead acid batteries of any type that will be ruined quickly if you deplete them more than about 50% of useable capacity. So you don't need as many LI batteries for a given amount of storage capacity.

All this being said there are good uses for batteries in the home. Not that I think you would ever be able to completely replace the grid by the use of batteries in the home and not have a drastically slimmed down lifestyle. I live in an area where they are now planning to shut down the grid during high wind, low humidity, hot and dry times of the year. The fire danger is just too great. So I'm looking into a grid tied solar installation with partial battery backup. A system like that uses batteries just to feed a critical load panel that includes things like lights, fans, and the refrigerator. Something like that really makes sense for my location. You still would get the benefit of a grid tied system and wouldn't be paying an arm and a leg for batteries that one would still likely never get topped up in winter, even in California if you are off grid. We can get cloudy, rainy, overcast weather for up to a week at a time in winter.

>"Because there isn't the technology (yet) to use batteries to time shift your use of electricity to a cheaper time there just isn't a good way to get a similar benefit as grid tied solar panels would provide."

That technology already exists. It's market structures that limit the potential.

The market rules for trading real time pricing of retail electricity doesn't exist for microscopic generators in most US locations anyway. The amount of arbitrage you'd make on it would be pretty low at any standard time of use retail rate structures, but could be interesting if allowed to buy and sell at the wholesale LMP. Being able to aggregate them into ancillary services markets holds some potential in areas where that's allowed (like the PJM) and in areas where the there are both both capacity and demand response markets there is potential for even more value stacking.

The grid around here has gotten more reliable since Sandy, when power was down for 12 days straight, but even just last year we were out for 4 days in a row. After Sandy there was a rush to install generators. I did the same and now every year I have to change the oil, spark plugs and air filter and it has to run 5 minutes every week to keep the battery charged. So on my new build, I can either pump the money into another generator or batteries. I am planning on going the later route because for the price of a generator I can get 13kwh of storage that is tied to a solar array that won't shut off during an outage - and no more oil changes.

Note that there is already a well-known home battery product that is "using batteries to time shift your use of electricity to a cheaper time": the Tesla Powerwall. [1]

On my plan (with PG&E in central California) the peak rate is more than 3.5 times the off peak rate, so time-shifting can potentially make a real difference.

Also, if you're in a place where you buy power for a higher price than you can sell it (e.g. California, with its Non-Bypassable Charges), charging and discharging a battery will be a bit cheaper than using the grid.

That said, I tend to agree that the economics alone don't make it a compelling proposition (at least where I live). Battery backup, on the other hand...

[1] https://www.tesla.com/support/energy/powerwall/mobile-app/time-based-control

"Home batteries will always be a niche product. If you have a reliable grid where you live there is very little upside to buying them. You won't get any real return on the investment until the grid goes down."

Eric, if battery and solar/wind trends continue to provide better performing products for less money, building trends continue to provide better insulation, appliances and heat pump trends continue towards higher efficiency, and grid electricity trends continue towards ever higher prices, then it's not a question of "if" but rather a question of "when" it will become economically sensible to have battery storage in a house, and eventually have off-grid homes become common. The only question is time.

I understand that it really does seem like a pipe dream right now, but that's the way things go. If progress is to continue, the impossible eventually becomes possible.

I agree. Saying home battery storage will always be a niche product was way too strong. I meant to say it is now and probably will be for a while longer.

I think the German citizens that are doing this thing with batteries should be considered philanthropic, at least they should be if the utilities there are taking proper advantage of that storage capacity. They probably think they are gaining some personal overall benefit from the personal storage capacity. I have my doubts. There's just too many negatives on the ledger with large personal battery systems against the overall positives.

For my own case there probably is no way I could get enough PV panels on my limited roof space, in combination with batteries, to last through winter in our mediteranean climate. I'm sure the winter climate in Germany is more severe than mine. Those batteries can help the grid if they are properly utilized but they really won't help the home owner when considered in combination with the expense and limited lifetime.

For the same reason I also don't think even using batteries for backup is always wise. If the reason the grid is expected to go down has to do with winter storms then that means the batteries are not likely to last through the crises because there won't be enough sun to charge the batteries. The timing of expected grid interruptions is very important for backup batteries to work.

I hope no one gets the impression that I think batteries are a bad idea generally. I think the greatest benefit is at grid scale or slightly smaller scales. I'd even be willing to pay my share of the expense for grid scale batteries in the form of increased taxes as a ratio of my energy use. I'm afraid those German citizens with huge personal batteries are just subsidizing their fellow citizens that are without.

>"I think the German citizens that are doing this thing with batteries should be considered philanthropic..."

>"German citizens with huge personal batteries are just subsidizing their fellow citizens that are without."

That depends on the feed in tariff structure for the PV, which has fallen dramatically along with the installed cost of residential PV in Germany. In many or even most cases the cost of storage to minimize exports to the grid (remunerated at a pittance compared to full retail grid power or the lifecycle cost of PV) pays for itself within the warranty period under German rate structures. The same true in much of Australia as well.

Retail electricity in most of the US is still comparatively cheap, and PV comparatively expensive making it harder for that type of project to pencil out favorably here unless subsidized. In states with simple net metering there's no real financial case for a home battery.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in