GBA Prime subscribers have access to many articles that aren’t accessible to non-subscribers, including Martin Holladay’s weekly blog series, “Musings of an Energy Nerd.” To whet the appetite of non-subscribers, we occasionally offer non-subscribers access to a “GBA Prime Sneak Peek” article like this one.

Homeowners’ interest in energy efficiency measures waxes and wanes. During the 1970s, when oil prices repeatedly spiked upwards, everyone wanted to save energy. However, in the 1980s, when oil prices collapsed, Americans forgot about saving energy, and most of us reverted to our usual wasteful habits.

By 2008, oil prices were high again, and green builders were receiving lots of phone calls from homeowners who wanted lower energy bills. But between June 2014 and now, oil prices have collapsed again, tumbling from $115 to between $37 and $40 a barrel. This raises several questions:

- What’s going on with energy prices?

- What does the future hold?

- What do low energy prices mean for green builders?

New Year’s Day is a good time to make predictions for the year ahead. I’ll attempt to answer the questions I’ve posed with a list of ten points.

Before going through these ten points, though, it’s worth emphasizing the fact that the world oil market is fairly responsive to changes in supply and demand. When the demand for oil exceeds the supply, prices rise. When the supply of oil exceeds the demand, prices fall.

Right now, oil producers are pumping lots of oil out of the ground — at a time when efficiency improvements (for example, improvements in vehicle fuel efficiency) have slowed the rate at which demand is increasing. The predictable result: prices have fallen.

1. Interest in green building is down because energy is cheap

Let’s face it: most Americans don’t care too much about saving energy when energy is affordable. Compared to your cell phone bill, Internet bill, and cable TV bill, your electricity bill may seem reasonable. So why worry about it?

When energy prices drop, the payback period for energy-efficiency measures increases. Some homeowners are happy to spend $6,000 on attic insulation if the payback period for the investment is 10 years. Once the payback period stretches to 20 years, though, the investment seems less wise.

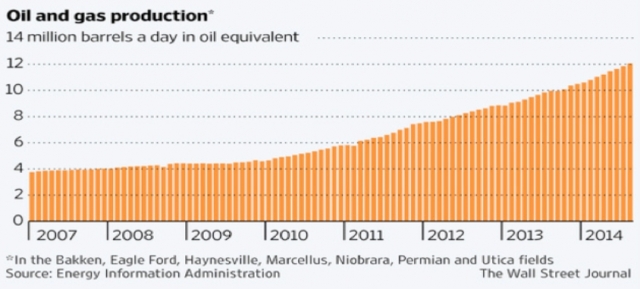

2. Fracking and new drilling technologies have dramatically increased U.S. oil and natural gas production

This is old news, but it bears repeating. The “peak oil” concerns of the late 1990s have faded due to the surprising increase in U.S. oil and gas production in the first decade of this century.

In an article published in January 2015, Fortune magazine noted, “The rise of hydraulic fracking from Montana to Texas to Pennsylvania has lifted U.S. oil production mightily, from 5.6 million barrels a day in 2010, to a current rate of 9.3 million.”

Of course, the U.S. wells that caused this dramatic increase in oil and gas production were drilled when energy prices were high. The resulting glut of oil and natural gas has contributed to the collapse of oil prices, and the collapse in oil prices calls into question whether oil and gas companies can justify further drilling. Finally, there’s another wrinkle to consider: wells drilled using the new technology have a shorter productive life than wells drilled with older methods.

The final result of the interaction between all of these factors is far from clear: the U.S. may end up with a surplus of oil and gas for decades, or the current glut may be an anomaly.

3. The oil sands business in Alberta is in trouble

Oil producers in Alberta, Canada, have made huge investments in facilities that extract oil from bitumen-laced sand. But extracting oil from tar sands is expensive. The process requires lots of money, lots of energy, and lots of water. The environmental damage from the process — including problems related to deforestation, water pollution, CO2 emissions, and the creation of tailing ponds — is alarming.

It’s so expensive to produce a barrel of oil from the tar sands of Alberta that this type of production isn’t profitable unless oil prices stay high. Since world oil prices have collapsed, the oil sands business is in deep trouble — and that’s good news for the environment.

On August 24, 2105, the Toronto Star reported, “Analyst Menno Hulshof said more than three-quarters of Canada’s daily output of 2.2 million barrels of crude from the oil sands is being produced at a loss at current prices. He said thermal oil in which steam is pumped underground to heat reservoirs so bitumen can flow to the surface is losing money on every barrel produced.”

A September 2015 report from the Business News Network explained that the tar sands industry is in decline, but that the full collapse of the industry is going to take several years. The story noted, “Mining for bitumen in the oil sands of northern Alberta is among the most expensive ways on earth to produce crude, but in the Fall 2015 Oil & Gas Overview report published by Peters & Company this week, miners believe there is ‘no oil price low enough’ for them to significantly scale back on production. That is largely because of the significant costs involved in shutting down such massive industrial processes and then attempting to restart them when prices rebound. As a result, Peters expects oil sands production to continue rising steadily until 2020 regardless of what happens with the price of oil. After 2020 is when oil sands production will stall without a significant price rebound.”

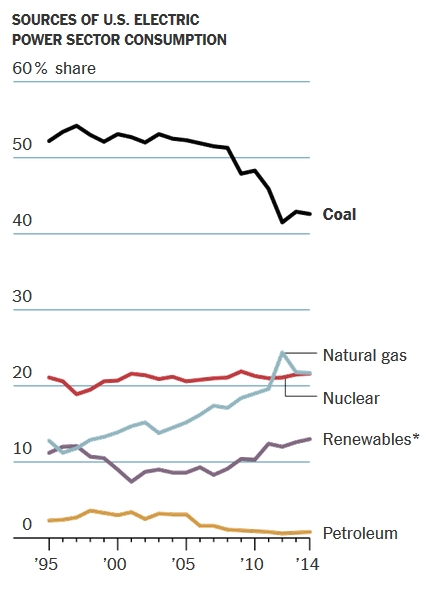

4. The U.S. coal industry is in steep decline

U.S. coal companies are beginning to go bankrupt. While this news is distressing to workers in the coal industry, it amounts to more good news for the environment.

In a story published on December 3, 2015, the New York Times reported that “a wave of a half-dozen bankruptcies has hit major coal companies. … Hal Harvey, chief executive of Energy Innovation, a policy research group, said that even though countries will continue to burn a lot of coal, the broader trend of coal’s decline is clear. ‘It’s not whether, but when,’ he said.”

5. Dropping oil prices aren’t killing the PV and wind industries

The price of photovoltaic (PV) modules is dropping so fast that even low oil and gas prices aren’t enough to put much of a dent in the PV revolution. This flies in the face of conventional wisdom — it used to be said that “low oil prices are bad for renewable energy” — but it’s true.

In windy regions of the world, electricity produced by wind turbines is now less expensive than electricity produced by fossil fuel-burning plants — and the per-kW capital cost to build the wind turbines is much less that the per-kW cost to build a coal plant or a nuclear power plant. In many parts of the world, PV power is also cost-competitive with electricity generated by conventional power plants. These renewable energy sources are setting (more or less) a ceiling for electricity prices — a ceiling that is surprisingly low. These facts can be used to argue that we’re more likely to face a cheap energy future than an expensive energy future.

As GBA has reported, homeowners who invest in PV often discover that their investment yields a better return than corporate bonds or the stock market. All across the planet, the installed cost of PV is still dropping. In Australia, large residential PV systems are being installed for $1 per watt. Moreover, the U.S. Congress recently reauthorized the 30% tax credit for residential solar equipment — a move that will give a further push in the U.S. to the apparently unstoppable PV juggernaut.

The PV revolution has barely begun. When this snowball starts rolling downhill, get ready for an avalanche.

6. As battery prices drop, grid defection opportunities increase

The Achilles’ heel of off-grid PV systems is the high price of batteries. Most GBA readers know, however, that Tesla is now building a mega-factory in Nevada to produce lithium-ion batteries; once this factory begins production, battery prices are scheduled to drop. The longer the factory operates, the lower the expected price for the batteries produced there.

Meanwhile, competing battery manufacturers are predicting that they’ll be able to match Tesla’s prices.

There aren’t any technical hurdles preventing homeowners from generating their own electricity and storing the energy in batteries for use at night and on cloudy days. The only hurdle is economic. In areas where electricity costs are high and PV costs are low, it already makes sense for some utility customers to cut the cord and go off-grid — a move known as “grid defection.”

PV prices and battery prices are both trending downward. These trends show every sign of continuing for a few more years, so grid defection is likely to increase.

7. Electric utilities are facing major disruption

Electric utilities in the U.S. can be divided roughly into two groups. In the first group are solar-hostile utilities like We Energies in Wisconsin; these utilities are facing the future by kicking and screaming.

In the second group are solar-friendly utilities like Green Mountain Power in Vermont. These utilities realize that “distributed generation” is an inevitable part of the future grid. (Distributed generation is a term that describes small systems that generate electricity near where the electricity is used.) The most disruptive element of the distributed generation revolution is PV; electric utilities that embrace PV are likely to be more nimble than the “kicking and screaming” group.

Electric utilities that have invested in large, expensive fossil-fuel-fired generating plants or nuclear plants will probably have to write down some of their assets over the coming years, because the PV and battery revolution will make many of these plants unnecessary and therefore obsolete. This process will be painful for most utilities, many of which are likely to declare bankruptcy.

8. The Paris agreement shows that the international political mood has shifted

I’m a cynic. Here’s a cynic’s report of what happened at the Paris climate change talks: not much. All of the announced carbon-reduction targets were non-binding. And even if every country manages to meet the non-binding targets, the efforts will be too little, too late.

I’m also imbued with hope. (As philosophers of hope note, hopeful people look for results they cannot see, in the teeth of evidence undermining that hope. Hope is not logical.) Here’s a hopeful person’s report of what happened in Paris: The international political mood has irrevocably shifted. Unlike Republican politicians in the U.S., the leaders of most of the world’s nations now (a) understand that the planet’s climate is changing, (b) recognize that CO2 emissions due to human activities are responsible for most of this climate change, and (c) accept the necessity of implementing policies that will reduce or reverse the rate of climate change.

Once this political shift has happened, there’s no going back to the status quo ante — the bad old days when denial ruled.

9. Saudi Arabia may be beginning to see the writing on the wall

Right now, Saudi Arabia is pumping lots of oil and selling the oil on the international market. Fellow OPEC members wish that Saudi Arabia would reduce oil production — a move that might help raise the price of oil. Saudi Arabia has refused. So what’s going on?

We don’t know; all we can do is speculate. In Saudi Arabia, the cost of oil production is quite low — about $9.90 per barrel. In contrast, the cost of production is about $17.20 per barrel in Russia and $36.20 per barrel in the U.S. Because of these disparities in production costs, low oil prices hurt Russia and the U.S. much more than they hurt Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia’s decision to keep pumping large quantities of oil has led analysts to propose at least two conspiracy theories. Theory #1 is that Saudi Arabia is conspiring with the U.S. to cripple the economies of two rival oil producers: Russia and Iran. (Saudi Arabia has accumulated huge foreign currency reserves, and is thus better able to ride out several years of low oil prices than either Russia or Iran, both of which are relatively cash-poor.) Russia provides economic and military support to the governments of Iran and Syria — governments which are at political odds with the U.S. and Saudi Arabia.

Theory #2 is a variation on Theory #1. It holds that Saudi Arabia is hoping to cripple the oil industries of three rival countries: Russia, Iran, and the U.S. According to this theory, the U.S. is a victim rather than a co-conspirator.

I’m not going to comment on the two theories that I just summarized, in part because I’m not a fan of conspiracy theories. I’m more interested in a different explanation of what’s going on. It’s possible that Saudi Arabia’s leaders realize that we are in the last decades of the fossil fuel era. They probably see a variety of factors at play, including increasing international concern about climate change, the rapid development of electric vehicles, and dropping prices for electricity generated by PV modules and wind turbines. Saudi leaders may have concluded that they might as well sell as much oil as they can right now — because in a few decades, they may not be able to sell much oil at all.

An article published in the International Business Times on May 22, 2015 reported: “Saudi Arabia, the desert kingdom which was built on exporting crude oil, is predicting that fossil fuels will become a thing of the past by 2050. And the world’s largest crude exporter believes that in the not-too-distant future it will be exporting solar energy instead. … Speaking at a climate change conference in Paris on 21 May [2015], oil minister Ali Al-Naimi said: ‘In Saudi Arabia we recognize that eventually, one of these days, we’re not going to need fossil fuels. I don’t know when — 2040, 2050 or thereafter. So we have embarked on a program to develop solar energy.’ Al-Naimi added that ‘hopefully, one of these days, instead of exporting fossil fuels, we will be exporting gigawatts of electric power.’ He noted that oil prices as low as $30 or $40 a barrel wouldn’t make solar power uneconomic.”

10. Green builders need to focus on issues other than low energy bills

Most homeowners aren’t willing to spend much money to lower their energy bills. Green builders can respond to homeowner indifference about energy costs two ways: either indignantly or pragmatically. The indignant path might include exasperated outbursts — “think about our dying planet,” perhaps — along with attempts to educate homeowners about their ethical responsibility to use as little energy as possible.

The pragmatic path, on the other hand, requires green builders to accept homeowner indifference about energy costs as a fact.

I would advise green builders that it’s probably time to stop selling your work on the basis of low energy bills. According to most marketing experts, the new recommended mantra is “a green home is more comfortable than a conventional home.”

Some green builders use another marketing ploy: bragging that green homes are healthy homes. If you’re tempted to follow this path, be careful. There is very little evidence that occupants of green homes are healthier than occupants of conventional homes. Without any data to support your claims, it’s better to steer clear of any discussions about occupant health.

If you’re really, really lucky, you’ll get a few phone calls from clients who say, “I’m interested in lowering my carbon footprint.” Those clients are rare — but they are a lot of fun to work with.

Farsi-speaking readers can find a translation of this article here: “Green Building in the Cheap Energy Era” in Farsi.

Martin Holladay’s previous blog: “Climate Affects Home Design.”

Click here to follow Martin Holladay on Twitter.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

13 Comments

Response to Lloyd Alter

On the TreeHugger website, Lloyd Alter had this to say: "Martin writes that ‘The PV revolution has barely begun. When this snowball starts rolling downhill, get ready for an avalanche.’ Here is where I begin to disagree. The PV revolution can be snuffed out with the flick of a pen, as is happening right now in Nevada and the UK. Electric utilities are facing major disruption and they are fighting back. However there are some fundamental issues that have to be faced with the whole net-zero solar on every roof and batteries in every basement idea, and the ensuing ‘grid defection’ that Martin talks about. I don't see it as an answer; As the City of Toronto's chief planner tweets: ‘I'm suspicious of net zero buildings in the middle of nowhere. Unless you're a hermit, you need to drive everywhere. Net zero is disingenuous.’ More and more of us live in cities and are concerned about the impact of sprawl, and rooftop solar just doesn't work in that environment. Too many people and not enough roof."

Lloyd raises two issues here, one of which I addressed in my article, and one of which is a red herring.

The red herring is Lloyd's observation that we have "too many people and not enough roof." The PV revolution I discuss here does not depend on roof area. Cheap PV arrays are already being installed as shade structures for urban parking lots and are covering acres of land at the edges of cities and along powerline right-of-ways. Cheap PV is unstoppable. It makes no difference whether Lloyd's roof in Toronto is small or large, shaded or unshaded. The electricity can be generated anywhere, and Lloyd can still use it.

Lloyd is right that some utilities want to limit the spread of PV by raising rates or charging fees to customers with PV arrays. I described this trend in my article, using the example of We Energies in Wisconsin.

This trend is self-limiting, however, due to the drop in the price of batteries -- what Lloyd refers to as the "batteries in every basement idea." Again, the batteries might be in Lloyd's basement, or in his Prius, or at an electrical substation at the end of Lloyd's block -- they can be anywhere, and the size of Lloyd's basement is irrelevant. When a homeowner has the ability to decide whether to go off-grid, the utility will either need to adapt or shrink. Utilities can't just keep raising rates in hopes of killing the PV revolution.

Grid Defection Isn't Happening

In northern NJ, where our electric rates are up to 17 to 20 cents per kWh, and SRECs are selling at over $200, even with the 30% federal investment tax credit, grid defection isn't happening. And NJ has one of the highest installed PV system numbers in the US.

Even with falling energy costs, there's no prospect of our electric utility rates dropping anytime soon. I don't know why other than long term energy purchase contracts and the non-linked-to-energy-prices costs of energy delivery. Our energy utility bills are rising, not falling.

That would point to continuing increased demand for energy efficient homes and PV system installations.

Response to Len Moskowitz

Len,

You're right, of course, that grid defection isn't happening yet in New Jersey. It's beginning to happen on islands off Maine, however, and in some areas of Australia.

My point isn't that grid defection is a realistic alternative now; my point is that current trends show a dropping price for PV modules and lithium-ion batteries. If electric utilities try to prevent the PV revolution by raising rates as their customers use less and less electricity each year, what happens?

If utility-supplied electricity continues to get more expensive every year, and off-grid electricity continues to get cheaper every year, the lines will eventually cross. That's why any utility that thinks that it can solve this problem by raising rates isn't seeing the PV challenge clearly.

Response to Martin Holladay

Thanks for your response, Martin.

Working through the 2015 energy use numbers for our pre-certified Passive House, without the federal investment tax credit and the NJ State SREC program, and with PV systems at $3 per Watt installed (a total of $31k), it would take around 12 or 13 years to recoup the cost of the PV system. With those incentives and assuming SRECs continue to be offered, it takes only 5 to 6 years.

The incentives make it worthwhile. Without them, the payback time is on the edge of being too long.

Over the next few years NJ State will probably phase out SRECs, just as they phased out rebates for PV installations a few years back. The 30% federal investment tax credit was just re-approved through 2019, but it reduces its credits through 2021 to 22%, and then may disappear completely.

At the moment, grid defection depends on subsidies, and they're not high enough to make grid defection numbers significant. Subsidies are not going to increase - they'll decrease. Unless the cost of PV installations, including batteries, drop enough to exceed the benefits of the disappearing subsidies, and/or residential energy costs rise significantly, grid defection numbers probably won't increase significantly.

I'm wondering why, months after the study of the much lower PV installation costs in Europe was released, PV installation costs in the US are still at $3 to $4 per watt. Maybe it's because of the subsidies? Maybe PV installation costs won't come down until the PV manufacturers and installers feel the pressure of reduced demand due to reduced subsidies.

Response to Len Moskowitz

Len,

At PV costs of $3/watt, we're not seeing any grid defection in the U.S., except on remote islands. I get that.

You wrote, "Unless the cost of PV installations, including batteries, drop enough to exceed the benefits of the disappearing subsidies, and/or residential energy costs rise significantly, grid defection probably won't increase significantly."

You're exactly right. My prediction is that PV costs will continue to drop, and that some utilities will continue to raise rates. What happens next is partly a question of economics, and partly a question of politics. But the utilities can't solve the problem with higher and higher rates. Eventually, PV wins this battle.

I share your suspicion that PV subsidies contribute to some extent to the high cost of installed PV systems in the U.S. Eventually, the subsidies will go away.

You can't collect SRECs on off-grid production. (response to #2)

Of COURSE you won't have grid defection if it takes SREC subsidy to make it pencil-out favorably. And 17-25 cent electricity is still cheaper than the levelized cost of PV + battery at Q4 2015 pricing, if higher than the levelized cost of grid-tied PV.

By contrast, diesel fired island power is quite expensive and invites grid defection if the utilities push back on PV owners. Even before the recent roll-back of net-metering in Hawaii grid defection was viable there, in a state where the residential retail rates are running north of 30 cents, and now that new PV will not have the same benefits of the grandfathered-in systems, those selling grid defection kits are seeing even higher interest than previously.

The learning curves of PV and batteries are both on a steep curve, and it's only a matter of time before grid defection becomes a viable option in a 17-20 cent market. But LOAD defection is happening in NJ right now, and in every other US state with 15 cent+ electricity and policies that allow multiple business models for roof top solar (leases, PPAs, etc.), not just outright ownership.

Nevada's net-metering roll back does not grandfather-in existing PV, which invites power purchase agreement contract defaults on third party owned rooftop systems. That's an out & out gouge, a broadside attack on solar enabled by the PUC, but it's at best going to delay the onslaught of PV by a half-decade or so even if the ruling is allowed to stand. (It only went into effect this week, and it's going to be challenged in court.) But even at NV's cheaper electricity rates grid defection will become rational there before 2030, and given the PUC's demonstrated willingness to screw the PV owners to protect incumbent utility revenues those with the means will be increasingly inclined to not hook up their PV to the grid, once battery & PV become cheaper than grid-retail. Just a WAG, but I'm guessing ~2025 is the time frame for islanded independent micro-grids in new developments to start showing up in NV, as is already happening in parts of Australia. While the ratepayers at large might be better off if those micro-grids were hooked up to the main grid, utility pushback in the form of high hook-up fees and high monthly fixed fees makes it uneconomic, even in some places where the grid is already installed.

I don't want to speak for Lloyd...

But I do think he has a point. The two problems he mentioned are not either/or. The two problems taken together present a possible emergent problem. Taken separately, either issue is easy. If utilities can figure out how to use distributed PV (and incentivize people by buying power at a reasonable rate) people will install PV on places other than the rooftops of private homes. If utilities don't figure out PV, then people will begin to defect from the grid, and that will accelerate as PV and battery prices continue to fall. The emergent problem hinges on the fact that to defect from the grid, the PV panels need to be reasonably close to the defector's home. People just aren't going to run cables to the nearest parking lot of freeway. This will limit defection primarily to single family homes, severely curtailing the number of possible defectors, especially in an increasingly urbanized country. That square feet of rooftop per person metric becomes very important.

A possible solution to this would be the emergence of nano- and microgrid operators who install PV panels and buy batteries and supply power to an apartment or condo building, which is still macro-grid defection, but on a somewhat larger scale. I believe prices on hardware would have to fall by a lot before this strategy is feasible, however.

Response to David Hicks

David,

You're right, of course, that the only people who can defect from the grid are those who can install a PV array in a sunny location close to the building they intend to serve. The array can either be roof-mounted or ground-mounted, but it needs to be on the property. Those who live in dense urban neighborhoods, or who have shaded roofs, won't be defecting from the grid.

That fact won't limit the trends I identified in this article very much, however. Lots of properties in the U.S. have yards or roofs where PV arrays can be installed. Only a tiny percentage of such roofs or yards now have a PV array. For utilities, the limiting factor to these trends will not be the "not enough roof area" problem. The utilities will be in deep trouble long before we run out of roof area.

What about the batteries?

What is the success rate on recycling the lithium-ion batteries from an economic perspective?

Thanks for the comment Martin

I do want to jump in again and say that I thought this is a really terrific and important article, and to thank you for bringing it out from behind the paywall because it is becoming part the much bigger discussion about where the green building movement is going. As you note at the end, the Passive House people are jumping all over comfort, and the USGBC is hugging the WELL people and going for health. And hey, I agree with 9 out of 10 of your points!

I still remain worried about PV- it is going to take a lot of batteries to deal with the coldest days of winter and the hottest nights of summer, I just don't see how you can maintain a grid system to deal with the worst extremes while having the wealthier customers invest in subsidized PV on their roofs or properties. You end up with a utility that has to feed everyone in a pinch, but most of the time is servicing the poor and the urban, while having to buy power from the rich. No wonder utilities are complaining.

If they actually defect, terrific, they are reducing the load demand at those extreme times. But for everyone else, we should be promoting dramatic load reduction through insulation, good windows and quality building, instead of offsetting loads through rooftop PV and playing the net-zero game.

Response to Lloyd Alter

Lloyd,

Thanks for your comments and kind words.

The transition to a new type of grid -- one with more distributed energy production (mostly PV, but also wind) and more battery storage -- isn't an either/or choice between two alternate futures. It's going to be a gradual transition, and it is unstoppable. The utilities have to get used to it, because they have no choice.

We're never going to have a grid that has enough battery storage to get Toronto through a cloudy December without much wind (although Hydro Quebec can cover a lot of eastern Canada's winter electrical load). But cheap PV and cheaper batteries make all kinds of things possible, and reduce the need for expensive peak plants to handle occasional summer afternoon (or winter evening) peak events.

We still need good insulation, good windows, and good air sealing practices, of course -- measures that GBA promotes all the time. But electricity is likely to stay affordable, and utilities will be playing an entirely new role in the future. A few people will happily defect from the grid, and every time that happens, it will undermine the utilities' attempts to solve their problems by raising rates.

unknowns

I can see why this discussion is important. What I don't see is any general acknowledgment that it is , after all, just speculation. This uncertainty is in itself a good reason to hedge one's bets and make your personal situation as resilient as possible. Energy security is too important to leave to chance.

Granted, the average consumer will be as shortsighted about this as everything else. Those in urban areas are already at the mercy of many other potential disruptions.

Response to Brian Carter

Brian,

I disagree that my article is "just speculation." Out of ten points made in the article, eight points are defensible facts.

The ninth point -- the one about Saudi Arabia's motives -- notes that "all we can do is speculate" about Saudi Arabia's motives. While we don't know Saudi Arabia's motives, we have a pretty good handle on the country's current rate of oil production.

The tenth point is marketing advice rather than fact. Take it for what it's worth -- which, frankly, is not much. I'm not very interested in marketing, in any case.

For the most part, I avoided making many predictions, other than to note that the cost trend for PV equipment and batteries is heading downward.

Instead of making predictions, I noted that "Homeowners’ interest in energy efficiency measures waxes and wanes" because historically, oil prices have sometimes "spiked upwards" and sometimes "collapsed."

I also noted that "the U.S. may end up with a surplus of oil and gas for decades, or the current glut may be an anomaly."

In short, I'm not sure why you think my analysis amounts to "just speculation."

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in