Better information leads to better decisions—this is the idea behind a regulatory device known as “mandated disclosure.” Mandated disclosures are all around you, from calorie counts on fast-food restaurant menus to conversations with doctors around informed consent.

But the biggest experiment yet in mandated disclosure may be an expected U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission proposal to extend these ideas to climate impacts facing U.S.-listed companies. Climate disclosure rules would require publicly traded companies to release information to investors about their emissions and how they are managing risks related to climate change and future climate regulations.

While it is easy to spot climate change-related risks facing companies like ExxonMobil that produces and sells fossil fuels that contribute to global warming, hidden vulnerabilities exist for businesses across the U.S. economy.

Largely in response to investors clamoring for more information about climate risks, as well as pressure from green groups that believe disclosure will drive climate-conscious investing, SEC Chair Gary Gensler announced in 2021 that the commission would use its statutory authority to require climate-related disclosures.

The SEC planned to consider proposals for climate-risk disclosure rules at its March 21 meeting.

Today we announced that @SECGov will meet publicly on March 21 to consider staff proposals to mandate climate-risk disclosures by public companies.

Companies and investors alike would benefit from clear rules of the road. Here’s why: pic.twitter.com/li5osqvJkG

— Gary Gensler (@GaryGensler) March 10, 2022

As law scholars, we work on legal issues involving businesses and regulation. Here’s what you need to know about climate disclosures and some of the challenges the SEC faces in adopting them.

What investors want to know

Investor pressure for better information about climate impacts comes from two directions.

First, some investors want to avoid companies that will be affected by climate change. The company’s products may be regulated in the future because of their impact on the climate, or its supply chains may get more expensive over time. Investors want to know which businesses will be able to adapt and preserve profitability.

Second, many investors are interested in ESG investing, which involves assessing companies’ commitments to environmental, social, and governance factors. Today, ESG investing accounts for $17.1 trillion—or 1 in 3 dollars—of the total U.S. assets under professional management. The challenge for the SEC is to ensure that claims being made about the sustainability of a company are based on reality.

The trend toward ESG investment has led to an outpouring of voluntary disclosure: About 90% of companies in the S&P 500 publish voluntary reports disclosing statistics on things like carbon emissions and how much renewable energy they use.

Some large investors require disclosure. For example, BlackRock, a multinational asset manager with around $10 trillion under its control, requires companies it invests in to disclose certain climate information. The United Kingdom plans to require climate disclosure starting in April 2022, and the European Union has reporting rules in place.

But the U.S. has been slow to impose mandatory climate disclosure requirements. Public companies have only been subject to a more general legal standard that they not materially mislead investors. The SEC released guidance in 2010 to encourage climate disclosures, but it was unenforced and failed to prompt standardized disclosures.

Rule benders and the effectiveness of disclosure

Research on the broader use of mandated disclosure, such as for home mortgage lending and consumer product labeling, shows that crafting effective disclosure regulations is difficult.

One reason is that the companies can easily evade disclosing useful information while still complying with the letter of the law. These “rule benders” can be very creative. Consider the restaurant in New York City that was subject to a health inspection grading regulation and managed to disguise its “B” rating by simply adding “EST” to its display of its grade. Disclosure regulations can also fail when they don’t effectively communicate valuable information.

A study of one type of climate disclosure–emissions labels on consumer products–found mixed evidence as to whether consumers altered their behavior in response. Rule benders can exploit human tendencies to discount or filter out warnings by providing an avalanche of unnecessary information that confuses and overwhelms the intended recipient.

Expect court challenges

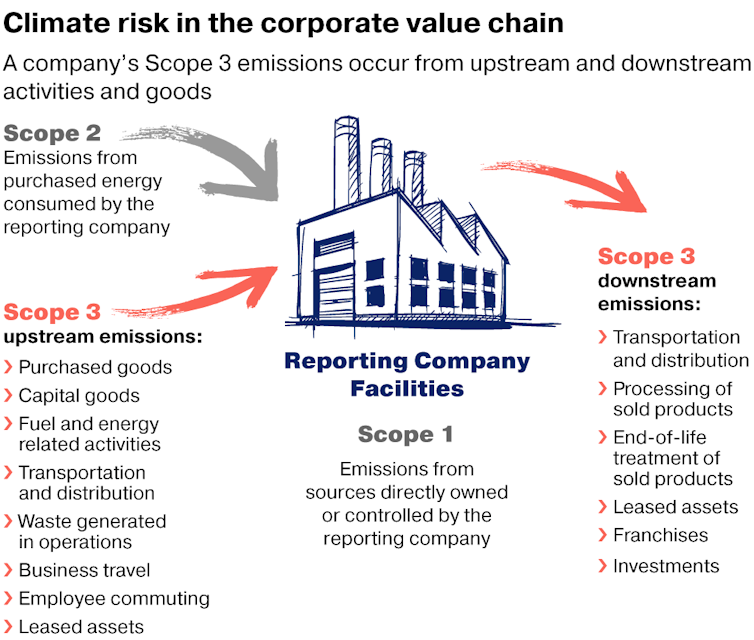

One challenge the SEC has grappled with is whether it has statutory authority to require companies to disclose their “Scope 3” emissions. These are emissions that a company doesn’t directly control, such as emissions from the use of its products or emissions in its supply chain.

A company like Amazon may have extensive upstream Scope 3 emissions in its suppliers’ transportation networks. General Motors would have extensive downstream emissions when people drive its gas-powered vehicles.

The SEC’s three Democratic commissioners, who make up a majority of the commission, have reportedly split on whether certain Scope 3 emissions can be viewed as “material” to investors and therefore subject to disclosure.

“Material” is defined as information that a reasonable person would consider important in making an investment decision.

Some critics of climate disclosures, including several Republican state attorneys general, suggest that the SEC has no authority to require disclosures that are not financially material. Missouri’s attorney general wrote that requiring climate reporting would impose “large costs and administrative burdens” on publicly traded companies. A group of senators suggested greenhouse gas-related assets would shift to private companies. West Virginia’s attorney general threatened to sue the SEC.

The costs of disclosure would vary. Some companies already intensely monitor emissions. Others would likely face high costs if Scope 3 emissions were included. An oil company, for example, might have to measure emissions from all the vehicles using its fuel.

The Administrative Procedure Act allows courts to vacate SEC rules that are deemed arbitrary or capricious because the agency failed to offer sufficient justification for choosing the proposal over alternatives. The SEC is acutely aware of this risk. A prior oil and gas extraction disclosure rule was invalidated by a court in 2013 as arbitrary and capricious.

Proceeding with caution

The SEC’s forthcoming climate risk disclosure rule will not be the final effort to use information to shape the private sector’s response to climate change.

What the SEC does now will affect those future moves. No wonder it is taking its time and proceeding cautiously.

Daniel Walters is an assistant professor of law at Penn State University. William Manson is a law student at Penn State. This post was originally published at The Conversation.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

4 Comments

“Regulatory burden” is a gross understatement. If implemented, the reporting will be very expensive and perhaps unaffordable to many smaller public companies. The result will be a shift to private equity and away from public capital markets.

If the SEC is arguing that these regs are needed to standardize ESG reporting, they can issue voluntarily guidelines to that end and forego forcing huge costs on public companies.

I didn’t see where the authors discussed the likelihood that the SEC is overstepping their regulatory authority. The courts will likely agree.

Hey Will, any chance you could give a ball park for what you consider to be ‘huge costs’, and some point of reference for how you came up with that number?

J-you have it backwards. It is incumbent on the regulator and government to calculate the costs and benefits of their actions.

But please apply some logic. Having started and run some businesses, (and occasionally teaching business,) I only have to look at the diagram in the article to understand how enormous the cost burden will be to calculate the Scope 3 emissions. Maybe Scope 2 items as well.

Imagine a small manufacturing company with 500 employees. Scope 3 is mandating the company calculate their total employee commuting emissions, one of many categories. Given the dynamic nature of those emissions—fluctuations in HR, changing commuting patterns, variable energy costs, opaque costs from public transportation—this is a heavy administrative burden.

Additionally, these are costs not directly controlled or borne by the company.

These costs need to be calculated and reported every 3 months for the company’s 10Q. It’s probably a full-time job or two just for this one metric.

Multiply this by all those categories. And likely more categories to be added down the road.

Maybe this isn’t a burden for the Apple’s of the world, but it’s a huge burden for the majority of public companies which are far smaller and less profitable.

One only has to look at passage of Sarbanes-Oxley to see this SEC proposal will be very costly. Additional—additional—audit costs from SOX have varied from $1 million for the smallest public companies to $100 million for the most complex.

And SOX is child’s play in comparison to what is being proposed, in my opinion.

I would also suggest that mandating reporting of these metrics opens the door to REGULATION of those metrics, e.g., having the government limit the aggregate emissions from your employees.

Perhaps all this is mooted when courts reject the SEC’s authority to impose these reporting requirements.

It's absurd.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in