Image Credit: Image #1: Fine Homebuilding

Residential construction practices in the U.S. have a certain Wild West flavor. Quality standards vary widely from one area of the country to another. For example, while builders in some regions pay meticulous attention when lapping a water-resistant barrier (WRB) or installing wall flashing, builders in other regions ignore best practice recommendations and code requirements.

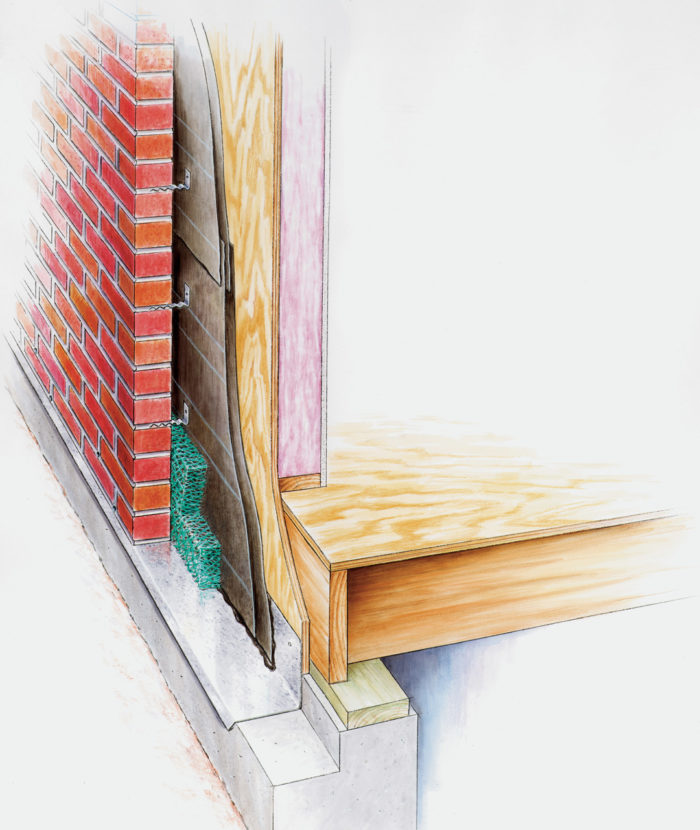

This article will focus on brick veneer over wood-framed walls. Although good details for this type of cladding were figured out decades ago, there are still areas of the country where these details are widely ignored. If you’re thinking about buying a house with brick veneer, it’s probably worth your while to learn about best practice recommendations for brick veneer.

It’s just siding

Until World War II, most brick walls were multi-wythe load-bearing walls. In other words, the brick walls supported beams, floor joists, and roof rafters.

Eventually, someone got the bright idea to build a wood-framed building with one wythe of brickwork on the exterior of a 2×4 bearing wall. Brick veneer doesn’t bear any loads; in function, brick veneer resembles vinyl siding more than it resembles the brick walls of yore.

What happens when masonry is wed to wood framing in this manner? Is it marriage made in heaven or a recipe for disaster? The answer depends on the flashing and drainage details.

Rain can get behind brick veneer

Before discussing best practice recommendations for brick veneer, let’s look at what happens when wind-driven rain soaks a brick-veneer wall. It isn’t hard for building scientists to study this phenomenon: all they have to do is remove the drywall and insulation from the exterior wall of a brick veneer building, and cut a few inspection holes in the sheathing. That way they can watch what happens when the exterior side…

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

This article is only available to GBA Prime Members

Sign up for a free trial and get instant access to this article as well as GBA’s complete library of premium articles and construction details.

Start Free TrialAlready a member? Log in

11 Comments

Holmlund Masonry

Through the wall metal flashing is hard to come by like in your first photo and I wonder how durable the flexible membrane types really are. A note on your last picture by Holmlund Masonry; the tar paper isn't lapped and what's the grayish stuff above?

Response to Greg Labbe

Greg,

I'm not sure what you mean by "metal flashing is hard to come by." Do you mean that its use is rare or that you are having difficulty purchasing lead-coated copper? A good sheet-metal shop should be able to order lead-coated copper for you.

Thick (30 mil or thicker) rubberized asphalt or EPDM flashing has been successfully used for brick veneer jobs for years, and I haven't heard of any performance issues with these types of flashing.

The photo from Holmlund Masonry shows a repair job. The photo is intended to show that repairs aren't easy. I'm not ready to vouch for the techniques shown in the photo, but I think that we should give the contractor the benefit of the doubt, because the wall is still open and the repair job is not complete.

lead coated

Does the copper really need to be lead coated? As Martin recently noted, lots of things are "toxic" but lead is toxic.

Response to Charlie Sullivan

Charlie,

Good question. According to one source that appears to sum up the reasoning behind the use of lead-coated copper flashing, "Copper sheet flashing is highly durable, corrosion resistant, and more easily shaped than stainless steel. It has a tendency to deposit green stains on brick and mortar adjacent to the flashing if exposed; lead coated copper sheet reduces staining substantially."

Some masons say that the lime in mortar can cause copper corrosion. According to the brief online research I just conducted, there doesn't appear to be any evidence of such corrosion. So I think it's safe to say that uncoated copper is an acceptable flashing for brick veneer jobs.

Hard to come by

Martin,

"Hard to come by" was a euphemism for "you never see through metal flashing on houses" and rarely on buildings. A new hospital wing near our place has stainless steel through flashing.

Response to Greg Labbe

Greg,

In most areas of the country, you're right -- you never see through-wall metal flashing on brick veneer houses.

Most residential builders have switched to peel-and-stick or EPDM products -- or are still in the Dark Ages, and don't know that flashing is required.

One other important element; couple of minor points

Because it's all but impossible to build brick veneer without spilling mortar down the space behind it, I believe it's essential to use a "bottom of cavity drain maintenance material". There are a number of options including keystone-shaped mesh pads, corrugated styrene, and non-woven gap material. We often use 3/16 non-woven gap material with a fabric scrim for the bottom 12-18" of a cavity, this has the added advantage of preventing capillary conduction of water via the mortar, since it maintains a gap between the droppings and the WRB and sheathing.

Copper does seem to start to verdigris very quickly when installed in masonry. In addition to the green staining that flows down from it, it seems clear that there is a chemical reaction with masonry and I am sympathetic to concerns over longevity from some sort of corrosive reaction. We haven't used lead coated copper in many years and instead use Revere's Freedom Gray zinc-tin coated copper, or their coated stainless steel material, which has been less expensive depending on the copper markets. (Generally we use flexible materials but at roof lines and other locations where a significant turn-down is required we use metal because it is pretty and UV stable, while the flexible flashings usually aren't.)

Some day I may see a brick veneer installed with a full 1" behind it, or even 2"...but I have never seen that yet either in new work or in old. Even the BIA calls it a 1" nominal air space. I think the key is keeping drainage open at the bottom and minimizing capillary moisture transport, and 3/4" +/- is just fine.

This guide

http://www.mim-online.org/uploads/media_items/a-guide-to-inspecting-residential-brick-veneer.original.pdf

is a fantastic illustration of how to do it right and all our supervisors have a copy...many newer or production-oriented masons have found it to be a succinct and understandable guide to the concept and execution of through-flashing, which in our area is often a new concept to them.

Don't forget your end dams!

Response to Douglas Horgan

Douglas,

Thanks for your valuable comments. I have edited my article to include a link to the publication you suggested ("Guide to Inspecting Residential Brick Veneer").

Another link and minor point

JLC recently ran another brick veneer article which I found better illustrated:

http://www.jlconline.com/how-to/exteriors/best-practices-brick-veneer-that-works_o

Reading it reminded me of another tip. We use two layers of WRB and specify that one should be low-perm such as #30 felt or taped foam board. That helps address both capillary transfer (which happens pretty quickly through one layer) and solar-driven moisture.

To make the 1" air gap effectively be an air vent, should the top of the brick wall also have weep holes? If yes, where could I find a diagram showing this detail? Also, what products can we use to keep critters from entering the weep holes and making the air gap as their new abode while still allowing drainage to happen? Thanks in advance!

beedigs,

The overwhelming majority of wetting and dryjng on brick veneer walls occurs by vapour movement through the bricks, not air movement in the cavity. The weep-holes are too small to be effective in creating a ventilated gap, and I'm not sure adding them to the top would help that much. If you wanted to effectively vent the top of the wall, you need some detail that leaves the whole gap open. As Martin says, their main function is to drain any water that makes its way into the cavity.

The weep-holes are protected by small mesh screens which sit where the mortar between the bricks would usually be. They can be bought at masonry suppliers, and probably online.

Log in or become a member to post a comment.

Sign up Log in