The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently released its long-awaited draft report on impacts associated with hydraulic fracturing on drinking water, completing the most extensive scientific review of published data to date.

At nearly 1,000 pages, it’s a substantial report. But it’s nowhere near a comprehensive evaluation — or even enumeration — of the risks that oil and gas development poses to both surface and ground water. The biggest issues aren’t what’s in the document, but what isn’t. For all its heft, the biggest lesson in the report is just how little we actually know about these critical risks.

Serious data limitations

First, the report is a review of existing studies. EPA did almost no original scientific research or fieldwork. Nor does it include much in the way of actual water quality reading — or baseline, pre-drilling data by which to compare. EPA doesn’t use this data because, for the most part, it doesn’t exist.

That’s a serious knowledge gap that needs to be filled. But in the meantime, it’s a mistake to think there are no problems just because they don’t turn up in the extremely limited data available. Indeed, EPA expressly acknowledges in the executive summary that “data limitations preclude a determination of the frequency of impacts with any certainty.”

While industry advocates are touting the report as wholesale exoneration, newspapers including The New York Times and Washington Post recognized that activities related to hydraulic fracturing do, in fact, pose real pollution risks to drinking water. Although EPA didn’t find evidence of hydraulic fracturing activities causing widespread, systematic drinking water contamination, they did find many instances of localized impacts to water supply and water quality.

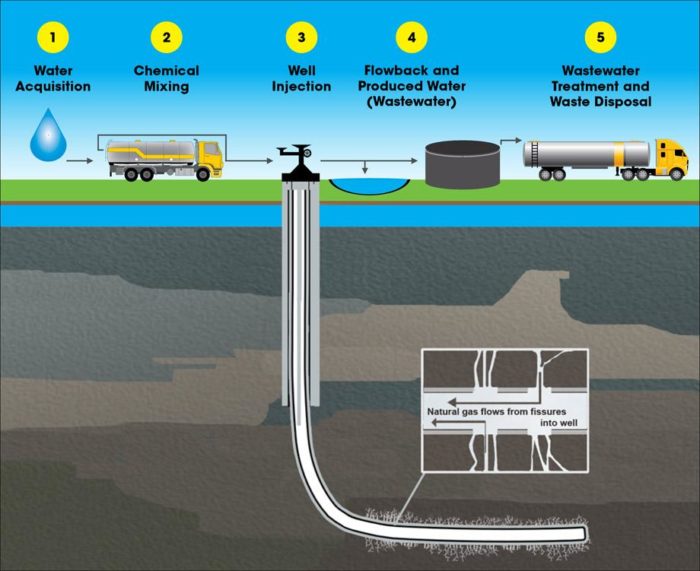

Even in the limited scope of activity studied in the report, EPA also referenced hundreds of spills of hydraulic fracturing fluid and so-called “produced water” — the mixture of hydraulic fracturing fluid and salty water found naturally underground that comes back to the surface once the well is drilled — many of which EPA says resulted in contamination of water and soil.

Just the tip of the iceberg

Because of the huge size and massive scale of these oil and gas operations, the risks, however well managed, are genuine and numerous. Hydraulic fracturing itself is just one factor, and not even the biggest one. Other key issues include the ongoing physical integrity of the wells and the storage, transport, and disposal of some 800 billion gallons of wastewater generated annually by onshore oil and gas operations in the United States.

Contamination risk associated with handling this wastewater is high, and the consequences can be dramatic. In many areas, this produced water is far saltier than sea water. It will kill plants, and can ruin the landscape for decades. It’s often laced with up to hundreds of toxic chemicals (antifreeze, to name just one).

Gallon for gallon, in other words, a water spill could be even more dangerous for the environment than an oil spill.

The potential for leaky underground injection wells to pollute water supplies, not evaluated in the EPA report, is another crucial pathway that is critical for regulators and industry to control. More than two billion gallons of produced water are disposed of in these wells every day.

Another emerging disposal issue is how to protect water supplies when we know little about the environmental characteristics of the wastewater, particularly in situations where industry is given the go-ahead to discharge it into rivers.

Flying blind

The impact of the unconventional oil and gas boom on our water supply is not well understood, and the findings of the EPA report underscore just how much work remains to be done to fully comprehend the risks, the magnitude of impacts, and the best ways to manage the risks.

Better and more accessible data on activities surrounding hydraulic fracturing operations is needed. There’s been some progress, and the EPA study is a step in the right direction in terms of better understanding this issue, but by no means are we out of the woods.

Between 2000 and 2013, almost ten million Americans lived within one mile of a hydraulically fractured natural gas or oil well. They deserve as much information as they can get. The Environmental Defense Fund’s oil and gas team is poring over the lengthy report and will post further analysis of the report’s various pieces, so stay tuned.

Mark Brownstein is a vice president in the climate and energy program at the Environmental Defense Fund, where this post was originally published.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in