Image Credit: Environmental Building News, January 1999. Energy data from Andy Shapiro, Energy Balance.

Having written about green building for more than twenty years now, I’ve encountered lots of misperceptions. One of those is that green building always has to cost a lot more than conventional building. There are plenty of examples where it does cost more (sometimes significantly more), but it doesn’t have to, and green choices can even reduce costs in some cases. Let me explain.

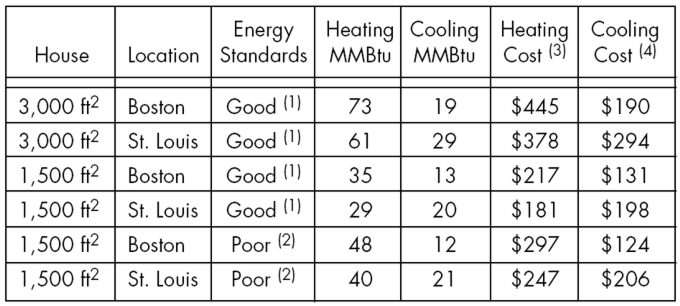

When someone is considering building a green home, my first, number-one recommendation is to keep the size down. Since 1950, the average house size in the U.S. has more than doubled, while family size has dropped by 25% — so we’re providing 2.8 times more area per person than we were back then. If you think you need a 3,000 square-foot house, consider whether 2,500 would suffice, or even less. There are some really great homes being built at 1,400 to 1,500 square feet — homes where every square foot is optimally used and there aren’t rooms, like formal dining rooms, that sit empty most of the time.

Often, because we’re conditioned to think that bigger is better or because we’re told by a real estate agent that a house has to be large to keep its value, we build the largest home possible. By stretching budgets to maximize square footage, we’re then often forced to skimp on quality and performance. If, instead, we downsize the house, we can improve its quality (durability, detailing, energy efficiency, green features), and we might even be able to reduce the overall costs.

With green building, there may be some other ways to lower costs that don’t require reducing the house size. At the development scale, if we design an onsite infiltration system for stormwater (rather than building a stormwater retention pond or installing storm sewers) that could both reduce costs and make the project greener. With larger facilities, it’s sometimes possible to save millions of dollars with such changes — paying for all of the additional green features.

Where we build can also influence cost. By clustering houses in a development, we can reduce the total amount of pavement, the length of utility lines, and other associated infrastructure costs. By putting a house fairly close to the access road, we both save costs and reduce the impacts of that additional pavement and material usage.

Relative to materials, there are some important ways to use materials more efficiently and save money. With “advanced framing,” studs and rafters (or roof trusses) can be installed 24 inches on-center, rather than the standard 16 inches, reducing the amount of wood used in construction. By carefully planning overall building dimensions and ceiling heights, one can optimize material use and reduce cut-off waste.

And it’s sometimes possible to have a structural material serve as a finished surface, obviating the need for an additional layer. This can be done when structural floor slabs are made into finished floors (often by pigmenting and/or polishing the concrete), or when a masonry block is used that has a decorative face, eliminating the need for another wall finish.

When it comes to energy, building a green, energy-efficient house usually does increase costs. But we can significantly reduce that extra cost — occasionally even eliminate it — by practicing “integrated energy design.” If we spend more money on the building envelope (more insulation, tighter construction detailing, and better windows) so that we dramatically reduce the heating and cooling loads, we can often save money on the heating and cooling equipment. With a really tight, energy-efficient house, for example, we might be able to eliminate the $10,000 to $15,000 distributed heating system in favor of one or two simple, through-the-wall-vented, high-efficiency gas space heaters, or even a few strips of electric resistance heat.

If, along with that really well-insulated envelope, we carefully select east- and west-facing window glazings that block most of the solar gain and provide natural shading from appropriately planted trees, we might even be able to eliminate central air conditioning.

These savings on mechanical equipment can cover a lot of the added cost of the improved building envelope. In rare cases, these savings in heating and cooling equipment (if we eliminate a really expensive system, such as a ground-source heat pump, for example), we can pay for all of the envelope improvements and even reduce the total project cost.

I invite you to share your comments on this blog.

To keep up with my latest articles and musings, you can sign up for my Twitter feeds

ED’s NOTE:

Strangely enough I published a short blog topic with almost the exact same title about a month ago. In it, I linked to several green home articles here on GBA that profile high quality, energy efficient, and affordable homes. Give it a peek!

–DM

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

17 Comments

Tax Credits

These days the measures above can be the tip of the iceberg. With federal, state, and local tax incentives added on building green can really become the preferred, rather than endured, budgetary option.

PassivHaus

Many of these ideas are standard in the PassivHaus concept which is very big in Europe (specifically Sweden) and is being pushed by a rare few here in the States. It's very exciting! I, as an Interior Designer would like to be more involved in PassivHaus and learn how to accentuate the positive of the concept and design to create an ambience that more would enjoy

Yes, it Works

Size and quality DOES make a difference. I designed a compact 2-br house with passive cooling in the living room/kitchen and one of the first unvented attic assemblies in the area. The average $35/mo electric bills attest that the homeowner's utility savings more than pay for the high-performance building envelope strategies.

"Since 1950, the average

"Since 1950, the average house size in the U.S. has more than doubled, while family size has dropped by 25% — so we’re providing 2.8 times more area per person than we were back then."

I find these statistics very useful and unfortunately, not shocking. Do you have the source? I'd like to have the source handy because I think a lot of people would appreciate the information. Thanks.

Source of Information

Cliff, in research I have done, I used the National Association of Homebuilders and the US Census to get these statistics. For presentations, I took this information a step further and found the cost of residential construction in 1950 and 2000, and made adjustments for inflation to determine the cost of residential construction per INHABITANT. That cost, adjusted for inflation, shows an almost four-fold increase in fifty years! It's my most successful point when talking with clients regarding sensible custom home design.

comments

I guess thats the trick. Im never sure when someone uses the term green what they really mean.

When it comes to building performance that is something that can be measured. Energy Usage can be measured. Air infiltration can be measured. A building of quality which requires attention to detail and execution. If we are comparing the cost of a high performance building to another building of quality there may be little difference in cost. If your comparing a high performance building to building that was constructed under minimal standards and with out the level of quality control required of a high performance building the answer is the high performance building costs more to build. Also a high performance building has additional factors that have to be taken into account and these factors make the design process more intense . Limiting Air Infiltration, High Insulation Levels, Avoidance of Thermal Bridging requiring additional design or detail considerations. In a high performance building it generally makes sense to have a low surface area to volume. Yet from a design and marketing perspective generally you dont want to end up with a insulated cube and you want to be able to build something looks and feels good. We are presently designing a group of 5 attached homes that we will try to attain passiv haus standards and also incorporate a quality design and still be in the cost ballpark of a quality home. Im pretty sure it can be done but i can see that the design process itself will be much more intensive and thats probably a good thing.

Watch Your Ratios!

All other things (viz. conditioned volume) being equal, perhaps. But the larger the building volume the lower the surface area to volume ratio. So that can be an excuse for a larger than necessary home.

As Alex correctly points out, the primary determinant of a home's energy use is its size. The secondary determinant is its shape. Small is more efficient. Simple shapes are more efficient.

And ain't that the rub?

Far too many confuse "green" with "energy efficient". I've been building green and energy efficient for 30 years. I was building R-40/60 homes when 2x4 R-11 walls were still the standard and everyone thought I was nuts. And I build whenever I can from locally-sourced rough-sawn (minimally-processed) native lumber, sometimes green right off the mill. Now that's green building.

My modified Larsen Truss 12" thick, cellulose-filled wall system with no sheathing also uses less wood than a conventional 2x6 OSB sheathed house. Now that's green building.

I also use no manufactured lumber, solid pine cabinets, no vinyl windows, no synthetic carpets or floor coverings and low- or no-VOC finishes. Now that's green building.

With the air-tight drywall approach (which does require some acoustic sealant or EPDM gaskets), I can achieve high levels of air-tightness (though I would never design or build to the absurdly unnecessary PassivHaus standards), but provide very high IAQ levels with a simple exhaust-only ventilation system. Where I build, there is no need for AC. My homes can be heated with just a woodstove and the sun (up to 50% passive solar), but sometimes include radiant tinted slabs that serve as finish floor. And my homes cost significantly less to build than similarly sized code-minimum homes while costing a fraction as much for heat, hot water and lighting. Now that's green building. You can take that to the bank.

Ratios and More Comments

I am not saying green is equivalent to energy efficieny but I believe efficiency of space design materials and energy constitute very siginificant and necessary components of what I believe to be green. When you say you have been building green and energy efficient ..... I seems like your describing two different concepts. When the term green is used it seems your talking just materials and their efficient use. I believe that a smaller and more efficient use of space is green both as to materials and as to energy use. I dont believe that the gains from energy efficiency should be used to encourage the building of larger spaces that doesnt seem green. By the way just out of curiosity how air tight are the homes that you build and what type of square footages are they. What do you believe the green standard for air tightness should be. It seems like you saying the passive haus standards are overkill and therefore wasteful with respect to resources ? What standards would be more optimal or green. Is there any definiton or limitation as to the size of a "green" home. I work in an urban environment where the metrics are a little different infill, multistory, non-combustible and we are trying to develop quality housing thats well designed, energy efficient and not saddled with the expense and maintenance of overly complicated systems. In my definition of green there is general preference for simple over complicated and passive over active. I also like performance based standards esecially when they make sense.

Green vs. advanced

Personaly, I feel that any defenition of "green" should include the word or the idea of sustainability. An ideal solution to energy efficiency should be repeatable en-masse and indefinately. The ends (energy efficiency) should not justify the means (use of non-sustainable materials and building practices). In my opinion, many homes that are called "green" should be more rightly called "advanced".

Green VS Energy Efficient

I would say that energy efficiency has no direct correlation to green. A high-tech synthetic-material house with the most advanced and efficient HVAC systems, perhaps even net-zero with the addition of PV or wind and solar thermal, is hardly a green house. While a small log cabin that uses only passive solar and a wood-stove is far more green even if it uses more BTUs/year.

Energy efficiency is an issue only because we build far bigger and more complex homes than we need, fill them with expensive and excessive appliances, cabinetry, furniture and toys, burn non-renewable global-warming fuels to heat, cool and power them, locate them on private lots often isolated from community services and work places, pay little regard to their impact on the local ecosystem or community, and create spaces for a more guilt-free high consumption lifestyle (with high resale value, because houses are - above all - commodities and investments).

The houses I've designed and/or built range from 768 SF (3 bedroom) to 1922 SF, with most in the 1200-1400 SF range. The only house I had blower door tested exchanged 2.13 ACH50.

How big is big enough - when it will meet the essential habitation needs of its occupants. How tight is "just right' - tight enough not to be wasteful, but loose enough to exchange some air on their own when the power is out. More importantly, all houses must "breathe" or transpire moisture, since no biological boundary in Nature is impermeable.

Robert I think I understand

Robert I think I understand what your saying. With respect to my inquiry as to any size limit to a " green home" The "how big is big enough" "when it will meet the essential habitation needs of its occupants".... I was looking for a more quantitative definition as opposed to conceptual. Who gets to decide what the essential habitational needs of the occupants are ? The Occupants, the Architect, Leed, Passiv Haus I see advertised and read about "green homes" some with interior floor plans many times the size of your 768-1922 sq/ft I understand theoretically some one can house a large and extended family and have essential habitational need for 10,000 sq/ft but my gut tells me most of these very large homes occupational levels are much lower per square foot than a more modest sized home. What I was asking was if there is any limitation on the size of a green home when it no longer can be considered green. Something like no more than 500 -1000 sq/ft of space per occupant ? I agree a high tech or net zero house made of synthetic materials is not a green house or an energy efficient house is not necessarily a green house. On the other hand I think conservative use of resources including energy is part of green and I guess while energy efficiency may not be directly correlated to green from the point of moving our society to where we need to be I think both conservation and energy efficiency will be key. No to knock the small log cabin that uses passive solar and wood burning stove thats great for New Hampshire or Vermont. I dont think it works for the Cities where most people live and work there has to be other green solutions. I agree all houses must breathe and transpire moisture I take that as a given but i dont think that is inconsistent with passiv house standards or concepts. Passiv Haus uses mechanical ventialation and the wall construction detail should allow moisture to escape. Aparently term "green" means many different things to many different people and as a label I guess its just buyer beware .

Concepts, Politics, Professionalism, and Reality!

Robert, thank for having your fortitude and vision. As you have stated; the size -square footage per person-of housing has grown way and far beyond the proportions of REALITY that I personally and may I be so bold - the worlds biosphere- would consider green, and survivable, in other words - way beyond what is 'appropriate'. And as you stated; the number of perks, luxuries and amenities that are touted by real estate reps and advertising far outweigh the application of 'green housing'. We here- have locally endured some ten years of development of such buildings and civic administrators that are justified it all by - it's what I always envisioned upon retirement' - or it is LEED'S certified and therefore somehow justified. Low tech is in fact High tech - for its demand for additional energy input is negligible as I stated in my papers for submission as a Building Technologist in 1983, and with experience in building of all phases commercial, industrial,residential and the majority of trades dating back to 1968.......and still adamantly maintain to this day. These views have sadly been substantiated by all the real statistics up to this new century and this very decade. I am deeply concerned that the more people picture their home as a profit rather than an equity for their family and the other people surrounding them, then the more difficult it has been and will continue to be to convince them of "appropriate design" - which is the approach I took both as a student, eventually as an Instructor of Building Technologies and eventually as a designer of residential and commercial spaces.

More Toys and More Wow = More Noise = More Cost = More Debt = More Impact on the Environment. My paper was one that addressed specific climatic zones as apposed to the "one concept fits all'. This is not a new challenge; this building "GREEN", it has been around for thousands and thousands of years, substantiated by the very survival of humans in various locations around the planet. This offers us through wisdom and experience ( if we bother to look: worldwide and historically) an opportunity to recognize the successes and the failures,culturally, economically and environmentally - how to survive. We do not need to look to the exorbitant costs of high-tech (self-promoting) companies to find answers to building green, it lies in the many thousands of years of humans trying to adapt to their specific climates. Many high-tech companies now have now copyrighted or patented concepts/ideas that are thousands of years old, that they have simply accomplished by utilizing the 'LAWS' that provide them that 'OPPORTUNITY" and reap the profits. Then there are the bureaucracies (governments and agencies) that invariably enforce the most expedient form of protocol that they can: based on the industry's criteria; thereby refusing to think outside any box, no matter where it comes from, its environmental impact, or the proven history of its application. The Innovators of today are those outside the box, just as it was 25, 50, 100, 1000 or 4000 years ago - 'cause the box is not a given or an absolute, it is simply the criteria you are initially convinced to operate within', so kudos to you who think a little outside of it, and not only walk the walk , but create reality from the talk,and encourage others to create beyond the "ordained" by bureaucracy and self proclaimed 'churches' of professional elitism. The fact that you look beyond the "Professionally and self-declared priesthood- IE: Leeds and all the others? Admittedly they are making a difference, even it is for their own sake - unfortunately at an incredibly high cost to the average person, family, community and the world. Green Design is NOT Green! Only" APPROPRIATE DESIGN "is in fact really Green!!!!!!! That is; design that is not based upon a political, economic or cultural agenda but one that simply addresses the needs and reality of the times, place, climate and resources of a given locale, and the planets capacity to respond positively . Thanx for doing what you do!!! My respect!

Regards R.

Houses do NOT need to breathe.

Great discussion here. Building smaller houses is of course one of the best things anyone can do to save energy and other resources, and I'm glad to see that the trend of larger houses has peaked and is now moving the other way. I personally am not fond of the word green, for the exact reason that you mentioned, Marshall: "I'm never sure when someone uses the term green what they really mean."

Regarding tight houses, it's best to get them as tight as possible--if not tighter--and then add mechanical ventilation. It's not a good idea to rely on random leaks for ventilation because there's no guarantee that that air will be the kind you want to be breathing. When the power goes out, Robert, the best thing to do is open the windows. Random leaks lead to poor indoor air quality in most/many cases.

Houses do NOT need to breathe. People need to breathe. Houses DO need to be able to dry out, but that's a separate issue from ventilation.

I like Joe Lstiburek's clear separation of the functions of the various parts of a house with the term 'control layers.' Building assemblies need to control the flows of heat, air, water vapor, and liquid water. Most people don't understand that very well and often confuse vapor barriers/retarders with air barriers. Sometimes they can be the same material. In most climate zones in the US, you have to be very careful not to overdo it with vapor retarders.

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD

energyvanguard.com

Don't Lose Sight of the Big Picture

Using less lumber is not neccessarily a "green" methodology. From an environmental perspective, wood products "fix" carbon; that is they remove it from the atmosphere. With all the concern we have about carbon-dioxide levels, perhaps we should view using more wood as the greener alternative. If less carbon is emitted to harvest, mill, and deliver the lumber than what it contains, it is a net gain in our efforts to lower CO2 levels.

Using lumber to fix carbon

John,

As used traditionally, lumber is carbon-neutral: a villager cuts down a tree and builds a house with it. When the house is old and decrepit, it composts and returns its carbon to the soil and to the atmosphere. A new tree grows on the compost pile, and the cycle is renewed.

This still occurs in the US: in the course of renovation and demolition work, tons of lumber are hauled to landfills every year, where the lumber rots through a combination of aerobic and anaerobic decomposition.

The only way your scheme to "fix" carbon will work is if we keep all of our new lumber dry forever and never let it rot. In other words, we build more and more houses, which cover all available land, and keep them in perfect condition forever, so no lumber ever rots. Is this sustainable?

I actually thought of a government-subsidized carbon-fixing program: we build huge barns all over the country, and fill them full of firewood. But we're not allowed to burn the firewood — we just warehouse it and keep it dry forever. As long as new forests keep growing, this program will work to fix carbon. Of course, pretty soon the world would be filled with many, many barns of useless firewood.

No politician has yet adopted my proposal.

No politician has yet adopted

Great article

Great article and I totally agree with what Lucas shared, glad Riversong is alive and exists for a period on this Earth, and Martin is a valuable well spoken asset to the Greater Building Science Community. Thank You ALL....

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in