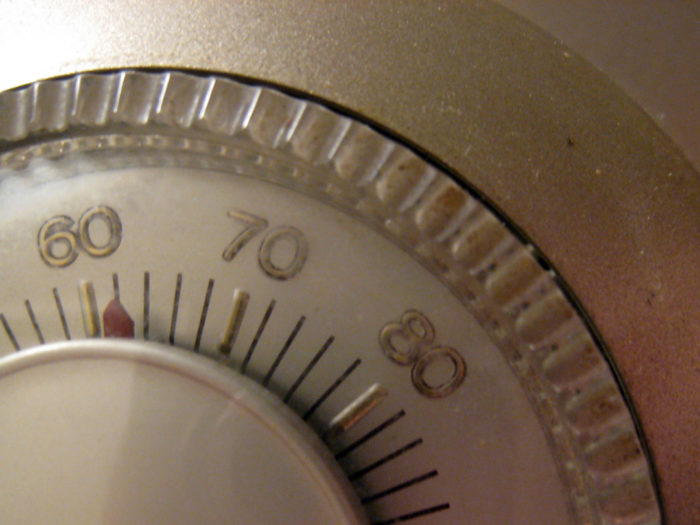

Image Credit: Jill via Flickr

Last Monday, scientists in the journal Nature Climate Change answered a nagging concern of practically everyone we know: why are offices and buildings so ridiculously over-air conditioned? The article reports the design of office buildings incorporates a decades-old formula, a significant part of which is based on the metabolic rates of the average man.

In other words, buildings are constructed so that a man weighing about 154 pounds feels comfortable while he is doing a desk job. This goes far beyond setting thermostats — that would make it easy to fix.

It does involve permanent building choices such as equipment much bigger than needed. As the study’s authors point out, over-designed systems lead to the very noticeable over-cooled result.

To be fair, if you read the references to the article, the guiding standard, ASHRAE 55-2010, (ASHRAE: American Society of Heating, Refrigerating, and Air-Conditioning Engineers) does not force anyone to plug a certain metabolic rate into the equation. It simply recommends values. It became the default standard for construction.

A behavioral scientist, or anyone who has keeps a wool jacket at work in the middle of summer to counter an incredibly cold office, can tell you that the power of this recommendation is huge.

The ASHRAE recommendation is a massive nudge in the wrong direction — not good for energy efficiency and perpetuates an outdated work environment.

Using established recommendations reduces stress

Unfortunately, recommendations like ASHRAE’s are not unique. Designing a building is a complex process that requires hundreds if not thousands of decisions. The very nature of so many decisions coordinated between a team of professionals creates uncertainties in the design process.

Standardized recommendations, from a respected source like ASHRAE, make designers’ choices much less stressful. Using those recommendations is easier than deeply considering, much less arguing out, the implications of each decision along the way. As a result, such recommendations are rarely scrutinized.

The process is reinforced by our brains which tell us more is better — so over-designing HVAC systems seems like a perfectly rational choice.

The unfortunate consequence is not only an unpleasant work environment but also frustration and bad outcomes for the fight against climate change. Defaults such as these make future efficiency improvements harder to achieve because once a building is built, we are stuck with the design for decades, at least.

There are opportunities for change

But the processes we just outlined also offer easy opportunities for improvement. Change the default so that engineers and architects are offered a more responsible choice.

We thought about this when we saw the major climate policy initiative announced by President Obama on Monday, August 3. The president’s Clean Power Plan rule for the first time puts federal limits on the amount of carbon that power plants can dump into the air. States get a lot of flexibility to consider and adopt a variety of approaches and measures that work best under their individual circumstances. The plan encourages invention.

We expect the best minds among us to take up this challenge. Likely their first thoughts will be to ramp up and improve alternative energy. We will see technological advances — more efficient appliances, for example, and rapidly improving battery storage for those sunless and windless days.

But what about some of the obvious energy efficiency treasures hiding in plain sight? ASHRAE 55-2010 is exhibit #1. We have several suggestions.

First, what if the design community or municipal building codes got rid of ASHRAE 55-2010? What if they adopted a much more efficient and demographically up-to-date standard as the default standard for designers and builders? Move away from an outdated default that makes wrong assumptions about the composition of the workforce, how it dresses (it’s not Mad Men sharkskin suits anymore) and energy costs.

Builders could always decide not to use the new standard, but solid research tells us that they are more likely to go with the new suggestion.

In fact, what if we collectively took a look at the entire process for designing and building infrastructure and elevated the most efficient choices to be the first or default choices? That brings us to our second point.

A nudge in the right direction can go a long way in an industry overloaded with product and design choices. Simply moving the most efficient products to the top of the list could have dramatic results and is relatively easy to do.

Just change the default settings

We could build these techniques right into the computer aided design tools every engineer and architect uses. A collective look at the entire process for designing and building infrastructure reveals opportunities at each phase.

Thinking about building design and efficiency in comparison to the highest performance or current industry standards, rather than just the average, could elevate new standards. The goal is that when quick decisions are made, those decisions tip toward a more efficient outcome — and fewer wool jackets in the summer.

Sorting out the mystery of over-cooled American offices is not just a curiosity. Behavioral approaches, of which this is one, are appropriate tools recognized by the Clean Power Rule. If we think about how ASHRAE 55-2010 became the building standard, we have the tools for doing better in the future.

[Editor’s note: In response to a variety of articles on this topic, ASHRAE issued a statement that said in part, “Earlier this week, research that looks at the method used to determine thermal comfort in Standard 55 was published via an article, ‘Energy Consumption in Buildings and Female Thermal Demand,’ in Nature Climate Change. The research looks at the method used to determine thermal comfort in ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55. ‘The interpretation of the authors regarding the basis for Standard 55 is not correct,’ Bjarne Olesen, Ph.D., a member of the ASHRAE Board of Directors, internationally renowned thermal comfort research and former chair of the Standard 55 committee, said. ‘The part of the standard they are referring to is the use of the PMV/PPD index. This method is taken from an ISO/EN standard 7730, which has existed since 1982. The basic research for establishing comfort criteria for the indoor environment was made with more than 1,000 subjects with equal amount of women and men. In the main studies, where they did the same sedentary work and wore the same type of clothing, there were no differences between the preferred temperature for men and women.’”]

Ruth Greenspan is a public policy scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars and a research associate at the Columbia Business School. Tripp Shealy is an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech. This blog was originally posted at The Daily Climate.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

4 Comments

Individual differences

Individuals may have very different preferences for their indoor workplace or home residence temperatures. The elderly may need temperatures above 70 degrees F. Those who are more active likely prefer a cooler temperature. The idea that a large building should be kept at a uniform temperature seems to be a problem. Having thermostats in individual offices or areas of the building, or ways to turn off ventilation in areas not being used, seem to be relatively simple and obvious ways to reduce energy usage and improve comfort. Finally, I've been in office environments where there were few thermostats. Those thermostats controlled temperatures in a large number of rooms, which tended to vary significantly in temperature. So many people had temperatures too cool or too warm for their comfort.

Where are these numbers coming from?

This GBA article begins by quoting an article from the journal Nature Climate Change, that "the design of office buildings incorporates a decades-old formula, a significant part of which is based on the metabolic rates of the average man."

The second paragraph begins, "In other words, buildings are constructed so that a man weighing about 154 pounds feels comfortable while he is doing a desk job." It's unclear whether that sentence comes from the GBA article authors, or from the Nature article, but the 154 pound figure is nowhere near the average weight for an American man, and hasn't been for more than 55 years. According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) data (first link below), quoted from the second link, "In 1960, the average American male weighed about 166.3 pounds". The same article again quotes the CDC, that today's average American male weights 195.5 pounds.

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/body-measurements.htm

http://www.newsmax.com/US/average-weight-man-woman-obese/2015/06/15/id/650546/

Wikipedia lists the average weights for adult males for nine different developed countries, and the lightest figure shown for Europe, North, and South America, is in Brazil, with an average weight of 160.3 pounds. The 154 pound figure is lower than the lowest figures I could find in the oldest charts for American males. I read the note at the end of the article, where ASHRAE disputes some conclusions of the Nature article. Does ASHRAE state an average weight for the person used in their calculations? The Nature article is behind a pay wall, so I couldn't see whether it contains the 154 pound figure. I'm curious about where this erroneous average weight entered the analysis.

The CDC reports that "the average American woman weighs 166.2 pounds". This contradicts two of the assertions of the GBA article, that the 154 pound average weight figure is too high for the American office work force, and that the figure would be lowered if the demographic included women. The quoted 154 pound figure is too low for American women, and much too low for American men. It appears that the authors believe that a higher average weight in the calculations leads to lower average building temperature settings, but the math behind that idea isn't delineated in the article.

The second paragraph of this GBA article ends, "This goes far beyond setting thermostats — that would make it easy to fix." While GBA has documented in many articles that oversizing HVAC equipment decreases efficiency, a majority of the objections in this article mention discomfort, with phrases like "very noticeable over-cooled result", "a wool jacket at work in the middle of summer to counter an incredibly cold office", "perpetuates an outdated work environment", "The unfortunate consequence is not only an unpleasant work environment", and "Move away from an outdated default that makes wrong assumptions about the composition of the workforce", "What if they adopted a much more efficient and demographically up-to-date standard", and "Sorting out the mystery of over-cooled American offices is not just a curiosity." Almost all of these statements ARE about temperature, which ought to be controllable via the thermostat setting (although there are often problems with exercising effective temperature control, as Robert Opaluch notes in his comment).

So I'm seeing three problems with this article, whose origins aren't clear to me. 1) The stated average weight for an American male is not outdated, it's simply wrong. 2) The authors say the problem isn't temperature setting, but then indicate that temperature is a major issue and the only mentioned source of occupant complaint. 3) AHSRAE says that the Nature analysis of their formulas and calculations is wrong, as the post-article note informs us, but we don't really get a look at what the ASHRAE defaults are, and how they influence office temperature or sizing the cooling system. Is there really any need to modify or abandon the ASHRAE recommendations, as this GBA article claims?

Might we have a follow-up article, to address these issues?

Response to Derek Roff

Derek,

Thanks for your comments.

The blog published here is a guest blog. GBA strives to provide information that is accurate, and our decision to publish this blog may not have been our best. As you know, guest bloggers on this site express a wide range of opinions, not all of which align with the views of the publisher (or me). I think that our site benefits from this wide range of opinion and the discussions that follow.

I agree that some of the statements in this blog seem unlikely, and I am grateful to you for pointing them out. We'll see if we can get the authors to respond.

I'm the one who wrote the Editor's Note at the end of the blog, in an effort to provide balance.

It's more complicated than "sexism"

I'd suggest this older but much better balanced NYT article on the same topic.

http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/sunday-review/enduring-summers-deep-freeze.html?

In this case, they actually consulted some thermal comfort experts about the multitude of complex reasons why buildings are chronically overcooled. A charge of sexism plays well in the media but it does a disservice to an important issue that is much more nuanced than that framing would suggest.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in