Here in the South, we love our humidity. It makes us glisten in the summer. But we also love our air conditioning and low humidity inside our homes. To save on air conditioning costs, more and more homes have attics encapsulated with spray foam insulation to bring the HVAC systems and ductwork inside the conditioned space. But there’s a problem.

High humidity in a spray foam attic

A few years ago, I wrote about the topic of high humidity in spray foam attics. When you encapsulate the attic with spray foam insulation and don’t do anything to condition the air in the attic, the humidity can get very high. It also stratifies, with the highest relative humidity near the ridge. The 2016 article I wrote on this topic shows the data for a house here in Atlanta.

With closed-cell spray foam on the roof deck, you have humidity in the attic but it doesn’t get to the OSB decking. With open-cell spray foam, however, the moisture goes into and out of the roof decking every day. During the daylight hours, especially when the sun hits the roof, moisture is driven out of the decking, through the foam, and into the attic air. At night, the moisture makes its way back through the vapor permeable spray foam and soaks into the OSB again. Do this long enough, and you can damage the roof.

Using an exhaust fan in an encapsulated attic

Since that time, we’ve been experimenting with ways to keep the attic humidity low. One of the methods we’ve tried is using a small fan to exhaust air from the attic. If the attic is properly sealed to the outdoors (and many spray foam attics aren’t), the replacement air comes from the conditioned space below the attic and is cool and dry. (Caution: I’m talking about a fan that moves a small amount of air, maybe 100 cubic feet per minute (cfm), not a powered attic ventilator, many of which move more than 1000 cfm.)

One of the houses we’ve tried this with is my own house in Atlanta. When I bought it, the attic had poorly installed spray foam insulation. In the fall of 2019, I had Woodman Insulation* come put a lot more spray foam up there using SES open-cell spray foam.* Before they arrived, though, I did a lot of prep work in the attic.

One part of that prep was installing an exhaust fan. I used a Panasonic FV-0511VQ1 WhisperCeiling fan. It’s efficient, quiet, and operates at either 50, 80, or 110 cfm of air flow.

Humidity data from summer 2020

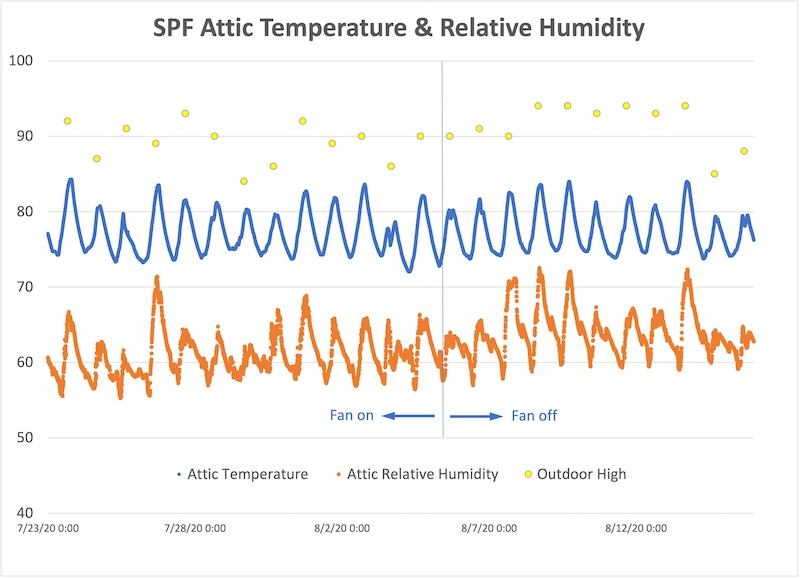

The graph below shows some of the data I recorded last July and August. The upper yellow dots are the outdoor high temperature for each day, the blue curve is the attic temperature, and the orange curve is the attic relative humidity.

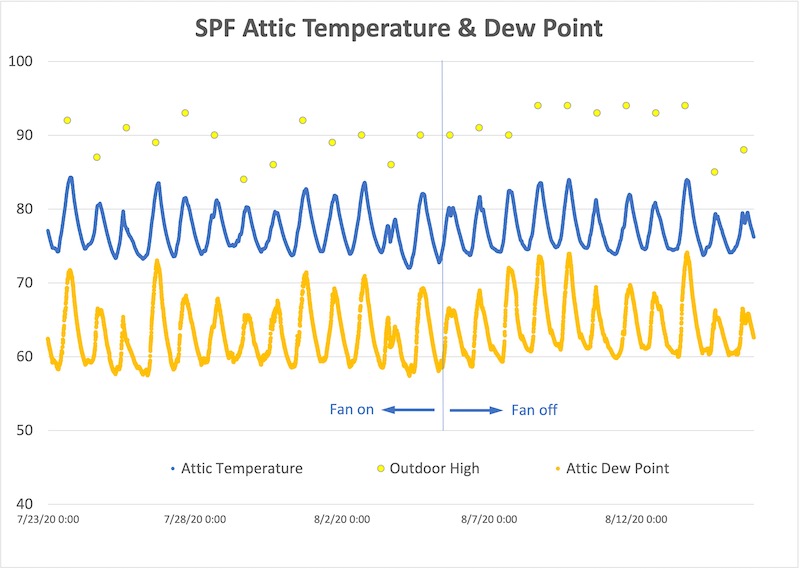

The graph above shows relative humidity. Below, I’ve posted the graph with dew point temperature. Interestingly, they both fall pretty much at the same place on the chart even though one is a percentage and the other a temperature.

Does it work?

The short answer is that I need more data. There does seem to be higher attic humidity with the fan turned off, but the outdoor temperature also got higher during that time. The good news is that in my house, the humidity is mostly reasonable even with the fan turned off. I don’t like the spikes over 70%, but the attic doesn’t spend much time there.

My data logger is still up there recording data, so I just need some heat and humidity to see how it performs this year. As I mentioned above, I had the exhaust fan set for 50 cfm when I ran it last summer. The building code doesn’t require any conditioning of the air in a spray foam attic. For roof lines insulated with air-permeable insulation (“the fluffy stuff”— fiberglass, cellulose, rockwool), the International Residential Code (IRC) requires 50 cfm of supply air per 1000 sq. ft. of attic floor area with a vapor diffusion port. With 2300 sq. ft. for my attic, I’d need 115 cfm, which is conveniently close to my fan’s maximum rate of 110 cfm. I’ll do that experiment this summer and get back to you.

The big drawback with exhaust ventilation (literally!) in a humid climate is that an equal amount of outdoor air is pulled into the house through the building enclosure. Using it in an encapsulated attic helps the attic by exhausting humid air near the ridge and replacing it with conditioned house air. Then the house has to do with a little extra humidity. It’s possible it could also grow mold inside your walls. Another way to exhaust from the attic would be to do it through an energy recovery ventilator (ERV), which I’ll try once I get my new Zehnder ERV installed.

Let me issue a word of caution to anyone considering using an exhaust fan in a spray-foam-encapsulated attic: This technique will work only if the attic is sealed tight. Many spray foam attics aren’t as airtight as they should be, so running an exhaust fan in them could make a humidity problem worse, not better.

The exhaust fan definitely works for one thing, though—and that’s spray foam odor. It’s not bad in my house, but I do notice a smell from the attic sometimes when the fan’s not running. With the fan running, there’s no odor in the house at all, even when it’s on the lowest setting of 50 cfm.

_________________________________________________________________________

Allison Bailes of Atlanta, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and founder of Energy Vanguard. He is also the author of the Energy Vanguard Blog and is writing a book. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

* In full disclosure, Woodman Insulation and SES provided their spray foam and the installation at no cost.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

5 Comments

> This technique will work only if the attic is sealed tight.

To clarify, you want the attic (conditioned space) to be well air sealed from the outside, but leaky to the rest of the house. It's mostly this ratio that determines where the replacement air comes from.

The primary concern with open cell is sheathing moisture - if this is what you have all the way to the sheathing, then it would be best to also measure this.

Would be interesting to test whether one could achieve equally low sheathing moisture with less energy by either timing the fan (only at night when radiant cooling is an issue?) or controlling the fan based on a humidistat.

There is no good solution to the large thermal bridge (the chimney)? Cover with rockwool?

Bill is it really 85° in your attic when it is 75° in the house only separated by a single layer of drywall?

When I see numbers like that I wonder if some or all of the old insulation is still in place on the attic floor.

When I see the words “encapsulated attic” in a building science article I want to scream. This is the language of the huckster spray foam salesmen. The word encapsulate suggests the attic is somehow magical separated from both the interior of the home and the exterior.

Seems to me I we call it a “conditioned attic” and install enough supply and return air duct to the attic keeping the attic within a degree or 2 of the rest of the house the moisture problem would be a nonissue.

Walta

It is difficult for me to tell from the picture at the top of the article - how long is the ducting for the exhaust fan? It might be an optical illusion, but it looks like the ducting travels quiet a ways in flex duct a few different times. I know the Panasonic fans are pretty good at moving how much air they say they are moving, but I haven't measured flow on a duct system that (appears) to be well over 25 feet w/ some segments of flexible ducting. I guess I'm curious what the cfm flow is of the fan through the ducting.

“[Deleted]”

I would never use an "exhaust only" fan in a house. It is going to create negative pressure somewhere. It appears from one of the pictures there is a wood-burning brick chimney in the house and more than likely this will become the fresh air supply. Using an exhaust fan to pull conditioned air out of the main body of the house to fight humidity is not the solution but simply a bandage that will soon lead to other issues. There are companies that use the same concept to pull conditioned air out of the main body of the house and exhaust it out of the crawlspace, and I have witnessed numerous problems with this concept. Keep up the good work and I look forward to reading your new book. I have to say, this appears to be the first article of yours that I have read and disagreed with.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in