If there’s one lesson climate change is teaching us, it might be this: we have to stop being surprised when places we think of as “safe” flood, burn, freeze, or suffer from life-threatening heat. Support for climate adaptation isn’t just needed for the coasts—it’s essential everywhere, especially in the low-income communities, communities of color, and other communities that may not have their own resources or capacity to invest in risk reduction. FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grant program, now entering its fourth year, aims to address that gap.

FEMA released the latest Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) for BRIC on October 12, which means that local jurisdictions, in partnership with states, territories, and tribal governments, can now begin the annual grant application process. Launched in 2020 to create a more robust and reliable source of funding for climate resilience and hazard mitigation, BRIC has evolved quite a bit over its short history. The newest NOFO continues to invest more FEMA resources in capacity building, provides additional incentives for states and localities to adopt better building codes, and introduces special considerations for the new Community Disaster Resilience Zones. However, there is always more work to be done to ensure that BRIC funding is distributed equitably and effectively.

For a refresher on the program, check out my original Building Resilience, BRIC by BRIC post from September 2021. We’ll cover the selected projects from BRIC’s third year in a separate post—stay tuned!

Funding availability

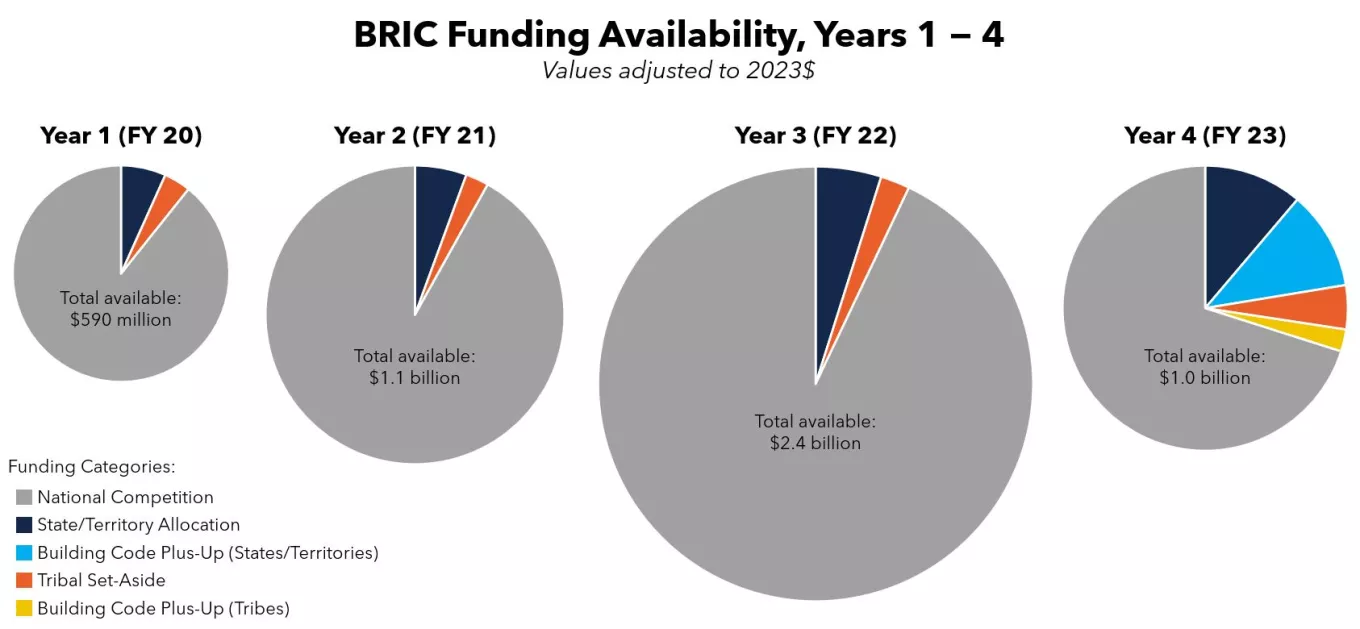

This year, a total of $1 billion is available across BRIC’s various funding categories, which is consistent with FEMA’s goals of having a predictable amount of funding available each year. Available funding was over $2 billion last year, but that one-time bump was largely due to the COVID-19 disaster declarations, which generated additional funding for BRIC. The program also continues to receive funding from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which is providing $200 million each year for five years beginning last year in Fiscal Year 2022. Funding for the state/territory allocation and tribal set-aside remain steady at $112 million ($2 million each) and $25 million, respectively.

Total funding for the BRIC’s fourth year returns to levels similar to Year 2, but with the addition of dedicated funding for building codes. Credit:Created by NRDC using FEMA data.

FEMA introduced a new category of funding this year, which is specifically for adopting and enforcing building codes. This “building code plus-up” will provide up to an additional $2 million per state and territory and $25 million for tribal applicants, in support of the Biden Administration’s National Initiative to Advance Building Codes. Unlike the state/territory allocation and tribal set-aside, if these funds are unused, they will not flow back into the national competition—this appears to be a one-time opportunity to advance the life- and money-saving benefits of modern, climate-smart building codes. Taking advantage of this building code funding should also improve applicants’ chances in future BRIC cycles. The national competition technical criteria already put considerable weight on building codes and the NOFO states that “in future BRIC cycles, FEMA may increase its emphasis on building codes criteria.”

Capability and capacity building

NRDC and many others have called for FEMA to increase assistance for capacity building, to ensure that lower-capacity communities have the ability to not only develop strong funding applications, but ultimately manage what can be complex projects. As I’ve noted in previous posts, BRIC funding applications disproportionately represent state and local governments that have higher levels of capacity. The BRIC program continues to have more applications than available funds, and lower-capacity communities are less likely to be able to even apply for funding—meaning they will have no chance of receiving grants regardless of overall funding levels.

FEMA’s approach to this challenge has been twofold. First, the agency is providing direct technical assistance to a cohort of eligible BRIC applicants, to support them throughout the project development and implementation process. After selecting only eight communities in BRIC’s first year, FEMA has increased its direct technical assistance offerings and will select at least 80 this coming year. FEMA also funds capacity building activities via the state/territory allocations and tribal set-asides. This year’s NOFO requires that states and territories spend $1.5 million of their $2 million allocations on capability and capacity building activities such as planning, project scoping, and community engagement.

While the amount of need still far outpaces this investment, reserving dedicated funding for capacity building is a good step forward, as is separating out funding for building codes so that states don’t need to choose between these important activities. FEMA should build on this step by creating a larger set-aside specifically for capacity building, while continuing to expand its provision of direct technical assistance and identifying ways to support community-based organizations via its grant programs.

Community Disaster Resilience Zones

This NOFO includes the first appearance of Community Disaster Resilience Zones (CDRZs), following the passage of the Community Disaster Resilience Zones Act of 2022. FEMA has designated 483 census tracts (so far) as CDRZs, using the agency’s National Risk Index and the White House Council on Environmental Quality’s Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST) to identify areas at high risk from climate hazards. The NOFO requires each state and territory to dedicate at least $400,000 of their allocation to activities benefiting CDRZs. Projects benefiting CDRZs also receive a preferential cost share (with FEMA covering 90% of costs instead of the standard 75%), and they receive a large number of prioritization points (40 out of a possible 100) in the national competition.

At this early stage, we don’t yet know how the full CDRZ program will be implemented (earlier this year, NRDC partnered with PolicyLink to comment on FEMA’s proposed CDRZ designation method and provide recommendations for the future). In the short term, though, communities located in a CDRZ should contact their state Hazard Mitigation Office as soon as possible to see if they could benefit from this funding. While only government entities are eligible to directly receive BRIC funds, community-based groups can partner with local or state agencies to help drive funds to the areas that need it most.

Prioritization criteria

The NOFO also sets out FEMA’s prioritization criteria for scoring and ranking projects in the national competition. This year, there are some key changes related to building codes, nature-based solutions, and equity and social vulnerability.

Building codes

Previously, FEMA’s criteria placed a high emphasis on statewide building codes. For example, last year, FEMA awarded projects up to 20 points out of a possible 115 if the applicable state, tribe, or territory had a mandatory, up-to-date building code adoption requirement. While it is understandable that FEMA wants to incentivize building code adoption (and at least one state does appear to be taking action as a result), this made localities in states without statewide codes less likely to get funding through no fault of their own.

This year, FEMA has changed the building code criteria to reflect both state and local code adoption, with 5 points for local codes and 5 points for statewide codes out of a possible 100. (Additional points are awarded for local building code enforcement ratings; this has stayed largely the same.) Projects that don’t receive points for local or state codes can partially make up for it by “demonstrating that they hold higher standards,” such as applying elevation requirements or prohibiting fill in flood-prone areas. This new flexibility seems promising, and it will be interesting to see how it affects the national competition selections, in combination with the additional funding for building code activities.

Nature-based solutions

Previously, FEMA took an “all or nothing” approach to nature-based projects, where all projects that incorporated nature-based solutions received the same 10 points, regardless of the scale or scope of the project’s nature-based components. That means a project that has a small nature-based component received the same points as a fully nature-based project. As a result, it has been difficult to determine how much BRIC funding is truly supporting nature-based solutions.

This year’s NOFO changes the quantitative scoring criteria for nature-based solutions: it creates two tiers, one of which awards fewer points for “neighborhood or site-scale” nature-based projects and another that awards more points for “watershed or landscape-scale” activities, “including those that support coastal resilience.” The top tier will award 15 points out of possible 100, which is a higher percentage of total points than has been available in the past.

Moving forward, we recommend that FEMA provide more detail on the nature-based components of each project, so that the public can better understand which projects include such elements and what proportion of the overall project cost will support nature-based solutions; continue to increase the number of points provided to nature-based projects, with meaningful distinctions between projects that include substantial nature-based elements and those that don’t; and create a dedicated set-aside within the available pot of funding specifically for nature-based projects.

Equity and social vulnerability

BRIC is covered by the Biden Administration’s Justice40 Initiative, which requires 40% of a program’s benefits to flow to disadvantaged or underserved communities. Now that the CEJST is available, FEMA is using that tool to identify priority communities and evaluate its Justice40 progress. Using the CEJST should help make FEMA’s work more consistent with other agencies’ and hopefully make it easier for communities to understand how the Administration is prioritizing its efforts. Projects that benefit “Justice40 communities” (as identified in the CEJST), CDRZs, and/or statutorily defined economically disadvantaged rural communities can receive up to 40 points under the BRIC technical criteria—the highest proportion to date—as well as additional points if they move to the qualitative review.

While FEMA has been making strides toward more equitable distribution of BRIC funding, there is always more to be done. In addition to the capacity building activities described above, FEMA can build on its progress by continuing to streamline its application processes and simplify benefit-cost requirements, share data and evaluate the effectiveness of its equity initiatives, update its own standards and regulations to reduce risk from climate-driven disasters, and build capacity within the hazard mitigation workforce. It’s also important to remember that BRIC isn’t an island: one grant program can only do so much, and broader shifts are needed to build truly resilient communities. For example, FEMA and other agencies should continue efforts to coordinate better with each other on adaptation and use the Justice40 targets as a starting point, not an end goal. And local and state governments considering applying for BRIC funding should also think about how their plans and projects intersect with other aspects of environmental (and economic, health, social, and other) risk and work to address the underlying root causes of vulnerability.

Looking ahead

As of mid-October, the United States had already experienced 24 billion-dollar disasters in 2023, a sobering new record. This is an uncomfortable sign that current investments in adaptation and resilience aren’t keeping up with the accelerating impacts of climate change. It’s critical that we not only increase funding for this essential work, but also ensure that it benefits the communities most affected by climate-driven hazards. With continued improvements, BRIC can be an important part of that solution.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in