I don’t call myself a green builder, but I discovered the intersection between economy and ecology through my work in affordable housing. During my 40-year career, I have built hundreds of homes with one thing in common: they were always the lowest-priced new homes in the neighborhood. Sometimes government subsidies helped, but I never relied on these alone to reach the desired price point because it’s difficult to lower construction costs sufficiently to achieve affordability even on free land.

Building affordability into the design

The first step to cutting construction costs is “affordability by design.” This means ensuring the basic blueprint of a building is optimized to minimize costs from the start. After numerous trials, I developed techniques inspired by the discoveries of an unlikely source, biologist Carl Bergmann. Bergmann noticed that larger animals tended to live in colder climates, where their size helped them retain heat more efficiently. This observation, known as Bergmann’s Rule, suggests that larger bodies have a better volume-to-surface area ratio, allowing them to retain more heat. So, how does Bergmann’s rule help reduce construction costs?

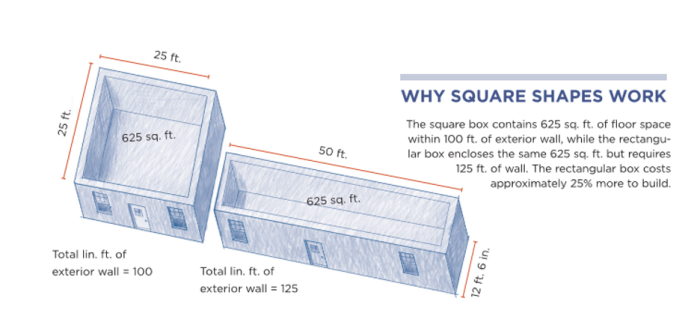

While buildings are not animals, they have area, volume, and a perimeter. Floor plan configurations require a ratio of exterior wall areas to interior volumes. To run a thought experiment, I drew two figures, one a square and the other a rectangle, both with an area of 625 square feet. Then, I calculated the perimeter of both shapes to discover that the square had a perimeter of 100 linear feet and the rectangle enclosing the same area had a perimeter of 125 linear feet. This was my eureka moment, as I realized the square shape would cost less to build because it had 25 percent less exterior wall—with its many costly layers of insulation, sheathing, water-resistive barrier, and siding.

I experimented with different shapes and sizes using a computer program to tweak building designs. Sometimes squares weren’t the most cost-effective option because they became too large for standard materials. However, my experiments showed consistent results.

One challenge was that I often had to build on narrow lots, requiring long, thin houses. So, I adjusted my formula to compare the area of the floor to the area of the exterior walls. This gave me a more precise ratio. Ideally, the ratio should be one-to-one, but that’s geometrically impossible unless you’re building a sphere. When I compared the square and rectangle examples using this new method, the square had a ratio of .78, which is good. Still, I found an even better ratio with a specific rectangle design: 24 ft. by 34 ft., which yielded a ratio of .88. If you run my earlier example, considering the wall area instead of the perimeter, you end up with a more accurate comparison.

My example of the square: 625 sq. ft. ÷ (25 ft x 4) x 8 = 800 sq. ft. wall = .78

And the rectangle: 625 sq. ft. ÷ 1000 sq. ft. wall = .62

My go-to shape is 24 x 34: 816 sq. ft. floor ÷ 928 sq. ft. wall = .88

The square yielded a ratio of .78, which is efficient, but I could improve on this even with a rectangle. I discovered that my tried-and-true footprint of 24 ft. by 34 ft. yielded a very respectable ratio of .88 sq. ft. of floor for every square foot of wall.

At this point, you may wonder, but what about bedrooms, kitchens, and baths? I always start my design process by finding the most efficient basic box for the lot. I draw all my rooms inside this box. I generally opt for a two-story to balance building spans and the area of costly foundations and roofs.

Economical design influences energy performance

Many years ago, I built an affordable split-level home that Fine Homebuilding magazine featured in an article titled “Building Affordable Houses.” The article detailed many of the elements I used to reduce construction costs, including installing electric furnaces. I did this to avoid the expense of gas piping and flues. I also upgraded the shell construction, windows, insulation, and air-sealing to reduce heating and air-conditioning equipment size and expense.

A reader wrote to the magazine accusing me of using an electric furnace to saddle my buyers with excessive heating bills. An electric furnace is cheaper to buy and install but costs twice as much to run. The reader had a point. Although I had not heard complaints about the utility bills in my homes, I asked the local electric company to run a comparative audit of my houses vs. neighborhood homes. The results surprised me and explained why I had no complaints—despite using an energy-hog furnace, my homes were at least 30 percent cheaper to heat and cool than the neighborhood sample. I attribute this benefit to the reduced volume-to-surface ratio and upgraded shell.

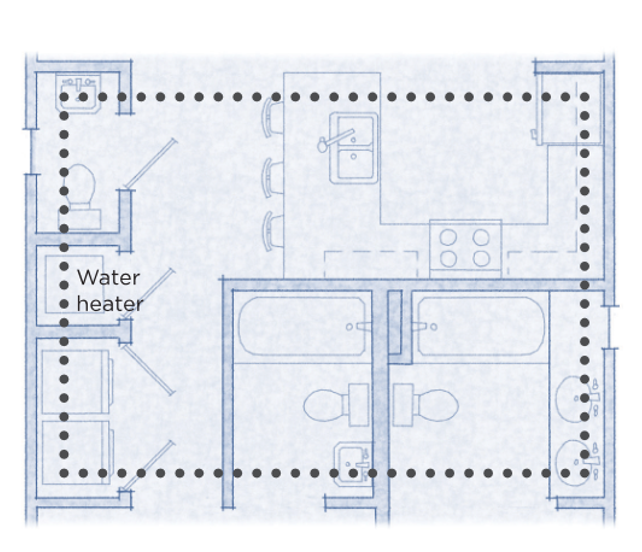

Once I have decided on my basic box, I locate the utility core as close as possible to the center of the house, moving it around only as required to design a livable floor plan. This location makes for shorter runs of costly ductwork, plumbing, and heavy electrical wiring. I recently began using Gary Klein’s “hot water rectangle” to analyze my plumbing layout. Klein aims to reduce time waiting for hot water to arrive at the faucet. His approach and the ratios he recommends help optimize plumbing locations to reduce the cost of water and sewer pipes much more than simply locating bathrooms back-to-back.

Beyond the box

My go-to building shape and the hot water rectangle are just two examples of how I try to rely on principles of cost reduction to design a house. But the truth is, I have discovered a consistent, albeit imperfect, relationship between being cost-effective and being green building–friendly. I apply all the material-sparing techniques available in the residential building code, from low-dollar foundations to advanced-framing methods.

In 2003, The Taunton Press commissioned my first book, Building an Affordable House: Trade Secrets to High-Value, Low-Cost Construction. It was published in 2004, coinciding with the rising popularity of the green building movement. During this time, CALGreen was in development, LEED 1.0 was running pilot projects, and even the Republicans (under George W. Bush) advocated for energy efficiency.

As popular interest in green building grew, I began receiving speaking engagements at green building conferences. To my surprise, my publisher informed me that my book had become a bestseller among U.S. and Canadian green building–materials suppliers. This recognition was a bit uncomfortable for me, given my self-concept as a conservative, hard-dollar guy.

However, with time, I’ve gained perspective. In the second edition of my book, available March 12, I explore the intersection of building economy and ecology in greater depth. I’ve come to realize that while I may have started as a conservative, cost-conscious builder, I now appreciate the importance of building homes that are not only affordable but also healthy, energy-efficient, durable, and environmentally considerate. I’m proud of the small contribution my homes make toward a better planet.

_______________________________________________________________________

Fernando Pagés Ruiz is a builder and an ICC-certified residential building inspector active in code development. Images courtesy of author, except where noted.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

22 Comments

BRAVO!! If we had more of this type of thinking we would have a lot less

societal anguish about housing affordability, availability, desirability, etc.

Thank you, gstan. I appreciate your words very much.

Brav0 x 2 :-)

I have to admit being immediately turned off by questions in the QA that start with "I'm building a 4500 square foot..."

Fernando, another highly recommended series (I'm sure you already read them!) is the "Not So Big House" series by Sarah Susanka. I have three of them and they are excellent with respect to interior design for smaller spaces.

I'll be searching out your books as I suspect they will compliment the collection quite well. Your design philosophy gives me hope :-)

Yes, of course, I know the fine work of Sarah Suzanka. I'm honored you'd consider placing my book next to hers on your shelf.

It's surprising that a non-square rectangular (henceforth just "rectangular") house could have a better floor/wall ratio than a square one, but the reason for it in this case is that the rectangular one is bigger. For a fixed floor area a square will always have a better ratio, and this ratio is unbounded. For the 24 x 32 example, a square with the same area has sides of length sqrt(816) = 28.6 ft. The wall area in this case is 914 sq ft--smaller than the 928 sq ft of the rectangle...but basically the same. The rectangle is still probably the better shape for other reasons. But note that a 32 x 32 house would have a ratio of 1. A 64 x 64 house would have a ratio of 2...but might a bit weird or expensive for other reasons.

What's your take on gable vs. hip roof? I watched a video a while back where the presenter claimed a hip roof is less expensive. I think the reasoning mainly came down to gable ends having walls that go much higher and thus are more costly to build/side. But does that really counteract the extra complexity of a hip roof?

The gable roof will be more cost effective, all common rafters vs the hip set rafters that are different and require more set up. Also, the hip roof is tough to ventilate properly.

Doug

If you're using prefabricated roof trusses, then the shape of the roof makes nearly no difference in terms of upfront roof framing cost. If you're site framing a roof then a hip is certainly more labor and expense.

Considering cost alone my first choice would be to use a prefabricated hip roof. This would greatly simplify the wall framing at no additional cost to the roof.

If you plan on actively using the attic space then I would go with a framed gable roof. It would be more expensive up front but give you the additional useful floor area of an attic, with no additional exterior surface area. I'm a fan of livable attics as part of the interior space of the house.

But if you really want to save money, go with no attic at all, and no basement. Give your house a nominally flat roof, with a good utility room at ground level, and soil conditions permitting, put it on a concrete slab on grade. The cost of making useful space in a full height basement can buy you much more floor area if you put that space at grade, on a slab.

This holds true if you're building on a nearly flat site. If you're building on a slope, where grading is going to be necessary and a walk-out basement is relatively easy to achieve, then a basement may be worth considering, especially if it can substitute for a second floor.

edit - Use 24" o.c. framing. Design on a 24" increment. There's no need to be rigid about it. But try to make the shell and interior structural walls work on a 2' grid. Some people go rigid about it for things like window and door openings as well. It's good, but not at the expense of messing up the design of other elements. Working on a 2' grid will reduce waste.

There's a big push to be doing continuous exterior insulation. Granted it offers some advantages but it comes at considerable complication to exterior finishes and door and window installations. Consider ways of achieving all your insulation inside the structural sheathing.

I agree with your advice, jollygreenshortguy, but invite you to look at this artcile about exterior foam and how to use it to save money. How to Get Sturdy Walls Without OSB: https://www.finehomebuilding.com/2022/07/06/how-to-get-sturdy-walls-without-osb

From the article you mentioned:

"My design made things easier because it’s a single-story house, mostly square, and not in a hazard area—no hurricanes or earthquakes to complicate things."

Yes, if you're building in an area with no high winds or earthquakes then you have more options. And if you're willing to structure your design around the very significant code constraints that come with the LIB (let-in bracing) approach, then you can do away with sheathing.

Well, pjpfeiff, it depends on the height of the gable end. If you have a simple roof with a low pitch, say 4/12, then the gable end is less costly. The cladding is more complex on a gable end, so sometimes, the equation works best on a hip if the gable end is prominent or you use expensive cladding, such as shake. But I'd usually go with the gable rather than the complexities of framing a hip.

There's a reason why the American Foursquare was the most popular prototype house form in the USA for many generations.

There's a reason why fireplaces masses were placed in the center of houses in New England and towards the outside walls in the South.

There's a reason for big porches in the South and a lack of them in the North.

So many of our current problems were solved in the past. If only we wouldn't forget.

Ditto, jollygreenshortguy, you're absolutely correct. And the old houses were 900 sf., 30x30.

Good morning. Thank you all for the kind comments and the excellent questions. I will reply to each one early next week. I am currently at the International Builders Show and am overwhelmed with activities.

Fernando, you've been an inspiration to me for as long as you've been writing about your approaches. Please keep up the good work!

I'm honored, Michael Maines. I appreciate your letting me know that my work has been useful.

Thank you for Building An Affordable House, Fernando. Reading it is very inspiring!

Enjoyed your article, very eye-opening. I look forward to getting your book.

Regarding the house you wrote about and built in 2002 for $45 sq ft, what do you estimate it would cost today?

Thanks!

About $100 a SF.

Thanks for the article. Reading this, and your 2002 article in Fine Homebuilding, is like looking at our own home, which was built in 1982 by a large cost-conscious builder. It's a two level rectangle- 40'x27' bi-level(split foyer) with full brick up to the gable and 2"x4" exterior walls above grade. Underneath the brick is a 1/2"- 1" air gap and then foil skinned foam panels attached to the 2"x4" walls, with appropriate bracing. This results in a wall assembly with an R value of app. 22, which is great. Our house also survived a 5.0 earthquake in 2002 without damage.

Our home is 200 amp all-electric, a consequence of gas shortages in the late 70s & early 80s. It's not a problem as it's very energy efficient and low cost with a good variable speed heat pump. We used 6,264 kWh last year, for the two of us. Our kids are grown and gone. The power company replaced the 44 years old buried neighborhood power lines in '22, but they left our shared, original 175 kVA transformer in the corner of our 1/4 acre lot.

The 5.5 kW tank water heater and air handler are located in lower level center, so short copper water line and plenum/duct runs. The hot water rectangle is 7.6%. By doing this rectangle calculation, I realized that our home's livable area is only 1,991 sf. The assessor and real estate people go by the exterior dimensions of 2,160 sf.

We were given the original sales brochure, as second owners, when we moved in back in '99. The original sales price was $52,225, which is $167,080 in today's dollars.

A silly question: I ordered this book via amazon but it did not yet arrive. What could be the reason? Is it already sold out?

Thanks for the article. You've been an inspiration to me. Please keep up the good work! https://iogames.onl/

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in