Image Credit: Osmany Cabrera

An upstate New York resident named Jim Savage has launched a web-based campaign to raise $60,000 and build a demonstration house with walls of hemp, lime, and water, advancing what Savage calls “the next step in green building.”

In a Kickstarter campaign that so far has attracted more than 90 donors, Savage lays out the case for choosing hemp over more conventional building materials, a technique he says has been used successfully in Europe for 25 years.

Hempcrete is a non-structural mix of shredded hemp (not marijuana) stalks, lime, and water. It can be packed into forms around structural framing to make walls, or can be used as insulation in conventionally framed buildings. Savage claims that the vapor-permeable material has an R-value of roughly 2.5 per inch, and is resistant to mold, insects, and rodents. It’s also non-toxic.

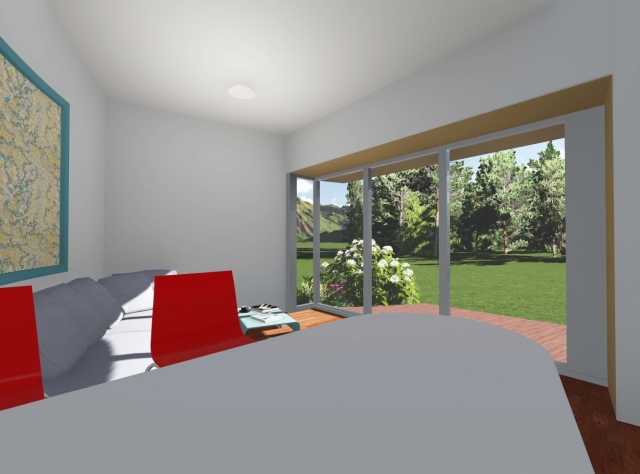

“HempHome Tiny+,” the house Savage and his colleagues would like to build in Catskill, New York, is a contemporary two-level design. Chief designer for the 400-square-foot house is Christina Griffin, an architect and Certified Passive House Consultant. Others working on the project include a North Carolina based hemp-lime design consultant, the head of the New York Hemp Industries Association, and Ken Levenson, chief operating officer of 475 High Performance Building Supply and co-president of the North American Passive House Network.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

Savage says that he was motivated by Hurricane Katrina and a devastating earthquake in Haiti to start GreenBuilt LLC and promote the use of hemp in buildings. Both disasters caused widespread housing damage and shortages.

“We searched for a healthy, durable, climate-resilient material that could provide high-quality permanent housing as well as temporary shelter,” the website says. “That’s how we found hempcrete.”

By telephone, the 67-year-old Savage said that he is a former Wall Street analyst who once researched industrial and electronic supply chains. “I was looking at how do you create a new industry that will be efficient, that will be competitive and that can become a sustainable supply chain,” he said. “Where housing came into it was, one of the great desperate needs all over the world is healthy housing. It was largely driven by my desire to make a better world, rather than my desire to make a lot of money. Obviously, it would be nice to make some. Figuring out the next electronic gadget was not what I wanted to do. I really wanted to make a difference in people’s lives.”

Hemp has attractive characteristics

There are a couple of things about hemp that make it an excellent choice for sustainable building, according to its boosters. For one, it grows very quickly — if you can grow it legally. Savage says that industrial hemp can grow almost a foot per week, and that enough hemp can be produced on a few acres of land in a single growing season to produce a 1,500-square-foot house.

Growing hemp is an effective way of sequestering carbon from the atmosphere. And because it’s non-toxic, it can be allowed to decompose without any environmental consequences. Hempcrete is vapor-permeable, won’t hold moisture and because of the lime binder, also is resistant to the growth of mold.

“It forms up almost like concrete,” Griffin said by telephone. “It has so many wonderful qualities because it’s vapor-permeable, so that if any moisture gets in it can come out. That, combined with the rapidly renewable aspect, makes it very attractive as a sustainable material.”

Because of extremely low levels of THC, the psychoactive component of marijuana, industrial hemp won’t give anyone a buzz. Still, Savage says, it’s considered a Schedule 1 controlled substance under federal law. It can legally be raised in scores of other countries, including Canada, and imported into the U.S. An agriculture bill signed into law in 2014 gives limited rights to land-grant universities and state agriculture departments to grow industrial hemp, and with the gradual loosening of marijuana laws around the country hemp’s wide scale acceptance may just be a matter of time. For now, Savage will import hemp from Europe.

He says that industrial hemp is used to make many products, including textiles and food, with $600 million worth of hemp products imported into the U.S. last year. Hemp-based bio-plastic parts are found in the doors of some Mercedes and BMW vehicles, and enthusiasts also are happy to point out that hemp fibers were in the paper on which the Declaration of Independence is printed and in the flag that Betsy Ross sewed together.

Performance characteristics not so clear

A key consideration in using hempcrete in a high-performance building is how effective it is as a thermal insulator, and how airtight a hempcrete wall would be. The plans for the prototype house in New York call for walls 12 inches thick with an R-value of about 30 or R-2.5 per inch, according to Savage.

Where does that value come from? Extensive testing in Europe, Savage says. At its website, American Hemp says that hempcrete has an R-value of 2.08 per inch (or R-25 for a 12-inch-thick wall). It cites as its source the British Board of Agreement (BBA), the equivalent of the International Code Council, which evaluates building materials in the U.S. through the ICC-Evaluation Service.

Tim Callahan, chief designer at Alembic Studio, an Asheville, North Carolina, firm that has completed three hemp-lime houses, says hempcrete walls typically have an R-value of 2.4 per inch, although that varies depending on the density of the material. He bases that value on testing conducted in Europe and offered a BBA report on a “tradical hemcrete wall system” submitted by a company called Lhoist UK Ltd. The BBA reported a 300 mm thick wall (11.8 inches) had an R-value of 15.4, while a 500 mm thick wall (19.7 inches) had an R-value of 25. That’s 1.26 to 1.3 per inch.

Callahan said that the R-2.4/inch value he uses in his energy calculations came from a company called Lime Technology UK, and that the Lhoist hempcrete was much denser, explaining its lower R-value. Callahan used the Lime Technology blend on a hempcrete house he built six years ago in Asheville, North Carolina, whose energy performance since then suggests that the 2.4 R-value is correct.

That house, which has 16-inch-thick walls, tested at 0.62 air changes per hour at a pressure difference of 50 pascals — barely missing the Passivhaus standard of 0.6 ach50. He said the monolithic nature of the walls is inherently less leaky than conventional wood-framed buildings because there are fewer potential joints between different building materials.

A search of the BBA website, and a follow-up phone call, didn’t turn up any references to “hemp” or “hempcrete.”

As to the performance specs on the Tiny+ project, Griffin has not yet done any energy modeling.

“We just haven’t gotten to that point,” she said, adding that specific performance numbers given for the project seemed a little “arbitrary.”

How do you build a hemp house?

Hempcrete construction looks a lot like straw-bale construction — you take a lot of minimally treated natural fiber and form it into relatively thick walls, then coat it inside and out with plaster.

Because hempcrete isn’t a structural material, it’s formed around an inner frame made from wood or other load-bearing material, as a video at this website shows. Builders start with strands of the woody inner core of hemp stalks and mix it either by hand or with a power mixer with a lime binder and water. The resulting mix of hempcrete is tamped by hand into forms built around an inner structural wall and allowed to harden. Then, the forms can be moved up and repacked with a new layer of hempcrete.

The Tiny+ house will probably be constructed this way, but Savage hopes prefabricated panels — a type of structural insulated panel (SIP) made from wood and hempcrete — may eventually be available. Griffin thinks that the roof of Tiny+ will most likely be insulated with cellulose rather than hempcrete, but those details, as well as the exterior finish, are still to be determined.

As to cost, Savage says the prototype house will be more expensive than conventional construction, mainly because of design features like curved walls. Generally, he said, a hempcrete house would be 7% to 10% more expensive than conventional construction, adding, “Once we have panelization really perfected, and the manufacturing more efficient, and certainly once hemp is legal to grow, it will be no more expensive than other building materials.”

As it looks now, the Kickstarter campaign will fall short of its $60,000 goal. “I don’t feel very positive about the money raised through Kickstarter,” he said. “You can see the fundraising is not going extremely well. But what’s happened is that we’ve gotten a great deal of interest from potential customers, from potential strategic partners, as a result of the Kickstarter campaign.

“If we don’t raise the money from the Kickstarter campaign, we expect we will raise the money in other ways, possibly from a buyer of the house, in order to make this happen,” he continued. “Our intention is whether we raise the money from Kickstarter or not, we are going to build this house.”

One Comment

'not marijuana'

Whew! I was nervous for a second.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in