Image Credit: Photos courtesy John Masmussen

Bates College was among the U.S. colleges and universities signing a pledge 10 years ago to become carbon neutral by 2020, in part by switching from fossil fuels to biomass to heat the 1 million square feet of space on its Lewiston, Maine, campus. Then something better came along — a Canadian biofuel made from waste wood that’s both cheaper and environmentally cleaner than the natural gas it had been burning, and without many of the logistical headaches that went with biomass.

The cellulosic biofuel produced by Ensyn has a 30-year track record, and is poised to gain new customers in the eastern U.S. Ensyn currently operates one small production facility in Ontario but has plans to open at least two more plants in North America and another in Brazil.

Although production is now barely a blip on the screen, roughly 3 million gallons a year, a biofuel made from wood holds intriguing possibilities for a heavily forested region of the country where fuel oil is still a dominant heat source. Nearly 360,000 Maine households, about 65% of the households in the state, burn oil or kerosene for heat. In Vermont and New Hampshire, oil’s share is about 45%, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, while the Northeast as a whole soaks up plenty of oil — just about 25% of all households use it for heat.

At a time when many heating customers are looking for ways to reduce carbon emissions, a regionally produced heating fuel with better environmental credentials than oil could be just what the doctor ordered. That’s especially true if switching fuels did not require a wholesale replacement of heating equipment.

The only rub? Ensyn’s biofuel, what it calls Renewable Fuel Oil, probably isn’t practical for residential use even as it lures new commercial and industrial accounts.

Not a blended fuel

Unlike the blend of gasoline and corn-derived ethanol that most of us use to fuel our vehicles, Ensyn’s RFO is not a mix of fossil fuels and something else. Lee Torrens, president of Ensyn’s fuels division, described it as a “pyrolytic oil.”

“What we do with wood is basically crack it, like they crack petroleum, and then reform it into a liquid,” he said. Ensyn’s innovation was learning how to increase the liquid yield typical in a pyrolytic process from one-third to 70%.

The fuel is about 20% water and it comes with half the BTU content of oil. When properly atomized it will burn just like boiler fuel, he said.

“If you looked at an ultimate analysis of our liquid and you showed it to a chemical engineer and said, ‘What is this stuff?’ they’d say, ‘It’s wood. It looks like wood.'”

The company estimates that the greenhouse gas emissions from burning the fuel are roughly 85% lower than they would be for oil.

“All the emissions from wood are biogenic in the greenhouse gas world,” Torrens said. “I don’t have to count the carbon coming off the stack because the carbon emitted was taken up during the life of that tree. On a life-cycle basis, it’s neutral. We don’t have to prove anything in that respect. Those are given factors that are used. The only thing that varies is what kind of tree, how it was harvested, how far did it go.”

Conversion costs are high

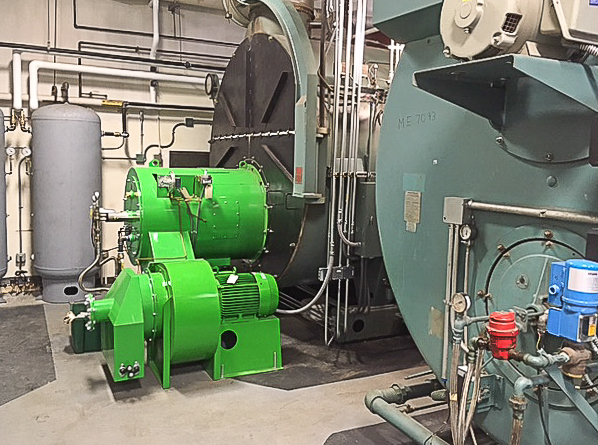

Bates College spent about $1 million to convert one of its natural gas boilers so it could use Ensyn’s biofuel, said Bates College energy manager John Rasmussen. The college goes through about 700,000 gallons of fuel in a typical heating season, so Rasmussen also added a 20,000-gallon stainless-steel outdoor storage tank.

The college needed new stainless-steel pumps and a new compressor; in fact, all plumbing for the fuel, up to an including the nozzle inside the combustion chamber must be made from stainless steel, because of the fuel’s high acid content. Also, to ensure proper ignition, the fuel must be heated to 160°F and delivered to the burner at 60 pounds per square inch of pressure.

Like many other college campuses, Bates is putting a new emphasis on reducing its greenhouse gas emissions, and the switch to Ensyn’s biofuel looked more attractive than a conversion to wood chips or pellets — another option Rasmussen had been weighing and one that Colby College, also in Maine, embraced a few years ago.

“This came along and we though, ‘Wow, this is fantastic,'” Rasmussen said by telephone. “We can get the same sustainability benefits. The fuel is more expensive than wood chips, but we would have had to spend $10 million to get a wood chip plant in here, plus the logistics weren’t good. We didn’t have a lot of land [to store] the fuel. We probably could have done it, but it would have been difficult, as opposed to spending a million bucks to convert an existing boiler.”

The biofuel is trucked from the Ensyn plant in Renfrew, Ontario, an hour west of Ottawa and nine hours from the Bates campus. That trip will be shortened to about four hours when Ensyn completes a storage facility south of Quebec, but ultimately Rasmussen would like to see the company build a production facility somewhere in Maine.

That idea is extremely appealing to a state with a strong forest products industry hard hit by recent downturns. Five paper mills have closed in the last three years as demand for traditional paper products fell, slashing thousands of jobs and creating a $1.3 billion hole in the state’s economy, Tux Turkel notes in a The Portland Press Herald report.

Fuel with a long track record, but obstacles remain

Bates College isn’t the only institutional user of Ensyn’s biofuel. Memorial Hospital in North Conway, New Hampshire, and a district heating plant in Youngstown, Ohio, are both customers, The Press Herald said, and Ensyn has landed a $70 million loan guarantee to build a new plant in Dooley County, Georgia, capable of producing 20 million gallons of fuel a year. The company is building a plant in Port-Cartier, Quebec, on the north coast of the St. Lawrence River, that should be open later this year.

With new plants springing up in the East, institutional customers will have more options for heating fuels, but homeowners are unlikely to reap many benefits.

“It works in smaller boilers,” Rasmussen said, “but not residential boilers. It would not be suitable for that.”

In addition to practical roadblocks for residential use, there also are market forces at work, said Pavel Molchanov, an energy analyst with Raymond James, an investment broker.

Ensyn has been a bright spot in the generally underwhelming cellulosic fuel industry, he wrote in a newsletter last summer. In a followup phone interview, Molchanov said that there’s more money to be made in transportation fuels than in heating, and that’s where Ensyn is likely to concentrate its efforts in the long run.

“The simple reason is that fuels that are what we normally think of as renewable fuels are designed for transportation,” he said. “In theory it is possible to use some of them for heating. As a matter of chemistry it’s possible to use them for heating, but economically that would almost never be a good idea. The simple reality is the cost of energy in transportation fuel or gasoline or diesel is always higher than it is in heating.

He continued, “If a company is making this product they will always want to sell into whatever market they make the most money in, and that is almost always going to be in transportation.”

“Their goal is to get into transportation, though,” Molchanov said of Ensyn’s long-term objective. “They do not want to be selling exclusively for heating forever. Clearly the economics in transportation can be better.”

Not a ‘black or white’ situation

“I don’t know if it’s black and white,” Torrens said. Where Ensyn’s biofuel ultimately goes depends in part on the price of oil and a complex Environmental Protection Agency program called the Renewable Fuel Standard. RFS, which is designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions as it promotes the use of renewable fuels, includes the use of Renewable Identification Numbers, or RINS, that companies like Ensyn create and then sell when they make renewable fuels.

RINS are sold to “obligated parties” like oil companies to help them meet program requirements. The RINS from the sale of RFO allow Ensyn to offer a discount to Bates, but changes in oil prices can affect the value of RINS and thus affect corporate decisions on where the fuel should go. Even so, Torrens said that Ensyn would not abandon its current heating customers.

Another factor is the push on college campuses to lower carbon emissions.

“A lot of these universities, Bates being one of them, have signed a climate change pledge,” Torrens said. “There were 250 of them once; now there are 900 of them. They signed initially in 2007. Now 10 years into it, people are saying, ‘What’s our progress?’

“Stationary heating nominally is between 30% and 40% of the greenhouse gas impact from a university,” he continued. “Everybody is going to great lengths to get renewable energy by buying [renewable energy credits], putting up wind, putting up solar, blah blah blah. But the elephant in the living room for some of these guys is their stationary sources and what you can do about that. This may be the only way to de-carbonize a district energy system.”

The other elephant in the living room is, of course, the fledgling Trump administration and what will happen to renewable energy and programs like RFS under the EPA’s new chief Scott Pruitt. That picture is still far from clear.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in