This post originally appeared at Ensia.

A group of manmade substances that can cause serious health problems in humans and animals is increasingly threatening U.S. drinking water systems, experts say. Scientists are working hard to better understand per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances—or PFAS—and develop technologies to minimize harm from these extraordinarily durable pollutants.

PFAS is the umbrella term for a variety of substances, including PFOA, PFOS and GenX. Exposure to high levels of PFAS may decrease vaccine response in children and cause some forms of cancer and birth defects. PFAS also affect the kidneys, liver and immune system, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Products such as firefighting foam, water-repellent fabrics, nonstick products, waxes, polishes and some food packaging contain the chemicals. Dubbed “forever chemicals” for their durability, these substances went unrecognized as pollutants for decades. But now that society is aware that they have contaminated drinking water, the race is on to develop technologies that can eliminate them.

“I think we’ll see more technologies evolving, but it’s going to be a tough one to crack,” says Ginny Yingling, senior hydrogeologist in the Environmental Health Division of the Minnesota Department of Health. “It took nearly a decade or more for people to figure out how to get after the chlorinated solvents. We thought they were impossible, [but they’re] nothing compared to these chemicals.”

Currently, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is involved in several research projects aimed at helping to clean up PFAS-contaminated sites. These include developing ways to measure PFAS in soil, sediments and groundwater; evaluating the effectiveness of methods for removing PFAS from drinking water; and evaluating approaches to destroying PFAS.

The EPA also has formed partnerships with other agencies such as the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), states and cities. In addition, the agency has partnered with public works facilities, such as wastewater treatment plants and waste processing facilities, across the country. It has also funded research in the private sector.

For fiscal year 2020, the EPA set aside $35 million for PFAS research. The DoD, which is dealing with contaminated sites at military installations across the country, budgeted $40 million for PFAS research.

Michael Regan, who President Joe Biden nominated to run the EPA, has experience dealing with PFAS. As head of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, he held the company Chemours—a spinoff of DuPont—accountable for PFAS entering the Cape Fear River.

Congress is looking to pump more money into research, particularly studies that are related to decontaminating groundwater, in the coming year. As part of the fiscal year 2021 DoD appropriations bill, lawmakers urged the secretary of defense “to focus continued investments in groundwater remediation towards demonstration projects that utilize commercially available methods to treat groundwater that are both cost effective and efficacious.”

Filter fix

Granular activated carbon—GAC—filtration is becoming a common approach for removing PFAS from water. However, the approach is inefficient and can be expensive, says Abinash Agrawal, a groundwater and soil remediation professor at Wright State University in Ohio.

In some instances, cleanup efforts use GAC to reduce the spread of contamination through groundwater. Contaminated water is pumped to the surface and then filtered through activated carbon tanks. The PFAS sticks to the carbon, leaving a toxic residue that must be hauled away and incinerated or dumped into hazardous waste landfills. The decontaminated water is returned to the environment, normally in a surface water reservoir such as a lake.

There’s a cost to incinerating the residue and setting up and maintaining the tanks. The pump-and-treat method can cost millions of dollars over 20 to 30 years, Agrawal and other experts say.

Filtra-Systems, a Michigan-based filtration company, offers a mobile water remediation service that can deploy to a site quickly and be ready to start the cleanup process in up to an hour, says Joe Haligowski, senior vice president of sales with the company.

The Voyager is a shipping container on wheels, which makes it easy to transport to contaminated sites around the country, Haligowski says. Depending on the application, water contamination level and water chemistry, the device uses walnut shells, ion exchange resin, granulated activated carbon and reverse osmosis membranes to remove contaminates.

Out to destroy

Scientists have been exploring ways to destroy PFAS in water, rather than simply remove it. This approach is preferable because it’s safer and ensures that the compounds don’t pose future risks, Agrawal says. For instance, under Agrawal’s guidance, Bo Wang, who was a doctorate student at Wright State in 2019, developed a chemical approach to rapidly degrade both PFOA and PFOS into non-toxic hydrocarbons using a metallic catalyst. The catalyst effectively treats groundwater contaminated with high concentrations of PFAS, Agrawal says. Agrawal and Wang, who is currently an assistant research scientist at Texas A&M University, hope to publish the findings within the next several months.

Agrawal notes that researchers in the United States and around the world are studying various PFAS destruction approaches. Some have reported destroying PFAS using ultrasound. Others are investigating bioremediation, a process in which microbes degrade the contaminant. It is one of the most cost-effective and passive techniques for eliminating PFAS in situ, Agrawal says.

A number of researchers are working in this area. For example, a year ago, researchers at Princeton University reported that an Acidimicrobium bacteria strain known as A6 degraded 60% of PFAS in lab reactors. The team has made slight improvements since and has been working to scale it up in an effort to get the right amount of biomass, says Peter Jaffé, professor of civil and environmental engineering and the lead researcher.

Even with the success this team has had, the approach may not be able to reduce the pollutant level to the EPA’s recommended limit of 70 parts per trillion for PFOA and PFOS together, Jaffé says. However, treating PFAS at the polluted sites and eliminating some of the pollutant by bioremediation is a good start, he says.

“You remove much of the mass, but at the end you still need something else to polish it off,” he says.

Bioremediation has also caught billionaire Bill Gates’ attention. He is backing Allonnia LLC, which is working to engineer and commercialize microbes that will eliminate PFAS in wastewater and soil, according to media reports. Allonnia launched in October with $40 million in funding.

The company will “bioprospect” for enzymes or microbes that can address specific challenges, Bloomberg reports, adding that the process is expected to take two years “before the spinoff is ready to pilot an effort in the natural world.”

Plasma technology

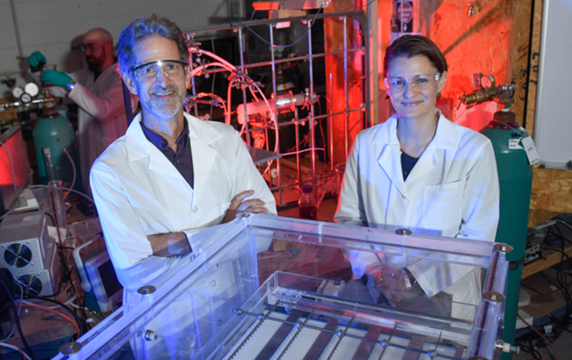

Another emerging approach is enhanced contact electrical discharge plasma technology, which uses superheated gases to attack and destroy PFAS. Developed with funding from the EPA and DoD, the technology is designed for ex situ — or above ground — treatment of contaminated groundwater. Selma Mededovic Thagard, a chemical and biomolecular engineering professor at Clarkson University in New York, and Thomas Holsen, a civil and environmental engineering professor at Clarkson, developed the technology.

Researchers at the University of Michigan and Drexel University in Pennsylvania also have developed plasma technology aimed at destroying PFAS.

Last fall, Thagard and her team tested the reactor at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, where PFAS has seeped into the local aquifer. The reactor reduced the PFAS concentration in a container of water to below detectable amounts in minutes.

The plasma technology is contained in a 16-foot trailer. Contaminated water enters the trailer at one end. Inside, high-voltage electricity creates conditions needed to destroy PFAS, says Stephen Richardson, an environmental engineer with the environmental engineering company GSI Environmental Inc., which designed the trailer. The reactor forms bubbles in the water that the PFAS sticks to. When the bubbles float to the surface, high-voltage electricity turns the PFAS into less harmful compounds.

In situ fix

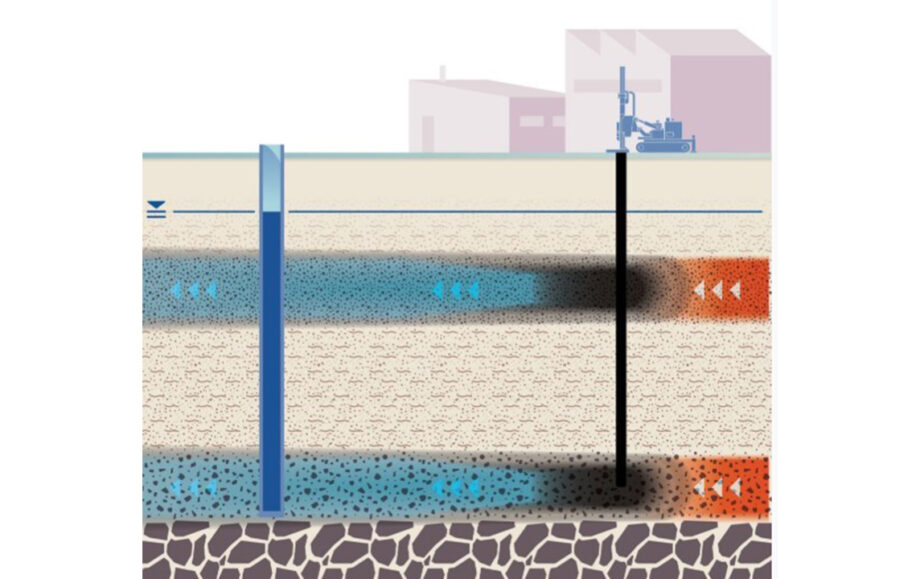

Perhaps the most effective in situ PFAS remediation technology available is a product known as PlumeStop Liquid Activated Carbon, Agrawal and Yingling say. PlumeStop is injected into the aquifer to filter the water while it’s still underground. Agrawal says it’s cost-effective, less disruptive and faster than other treatment methods currently available.

The technology was first tested at a contaminated site in Canada more than five years ago, says Scott Wilson, president and CEO of California-based Regenesis, which developed the product.

PlumeStop is created by milling coconut fiber activated charcoal (CFAC) to the size of red blood cells. The CFAC bits are then wrapped in a substance that prevents them from recoalescing into larger particles, Wilson says. The substance is pumped into the aquifer through holes drilled into the ground, where, he says, it forms a permeable water treatment zone.

“When it does that, basically you’ve converted the polluted aquifer into a purifying filter,” Wilson says. “The (PlumeStop) will pull all of the PFAS out and make it stick to the soil because the soil basically has been painted with this black carbon. So you’ve purified the water moving through that area, and it becomes super clean.”

The technology is relatively new, so there’s no way to determine how effective it is long-term or what the downsides might be. But Canadian groundwater remediation and mathematical modeling expert Grant Carey estimates the product can last between 40 to 60 years. Carey is president of Porewater Solutions, which does consulting work related to groundwater contamination.

Regenesis has applied PlumeStop to several EPA Superfund and DoD sites, including a Michigan Army National Guard base, Wilson says. Since the application in 2018, the company has monitored the site, and PFAS has remained at non-detectable levels for 20 consecutive months, Wilson says.

Regenesis is now figuring out how to apply PlumeStop to the unsaturated zone above the water table to prevent PFAS from migrating to the groundwater in the first place, he says. The product is expected to be ready for unsaturated zone treatments by the end of 2021.

Optimistic but …

Given the various emerging PFAS remediation technologies and the research that’s being done across the nation, Yingling and Agrawal say they are optimistic that scientists will find a solution to destroy the pollutants.

However, Yingling notes that addressing PFAS has been “such a patchwork,” and the EPA needs to issue a national strategy. A coordinated approach from the federal government would put a “little more wind in the sails of the researchers trying to find solutions.”

The EPA released a PFAS action plan in February 2019. Yingling says she’s aware the agency issued the action plan after much public pressure. But the EPA remains far behind in terms of addressing PFAS. The agency continues to deal with PFOA and PFOS, and it still doesn’t have a maximum contaminant level for them, she adds.

“I sympathize with the EPA; they have a much harder time of being nimble than the states do,” Yingling says. “But still, we need a national strategy, and they need to get on it.”

Ismail Turay Jr. is a staff writer at the Dayton (Ohio) Daily News. This piece was expanded and updated from an original report in the Dayton Daily News published in June 2020. This story is part of a nine-month Ensia investigation of drinking water contamination across the U.S. The series is supported by funding from the Park Foundation and Water Foundation. Read the launch story, “Thirsting for Solutions,” here.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

3 Comments

To connect this to GBA, I found an article that measured samples of building materials and other things. They found it in OSB and related materials, and,

"two samples of wood fibre insulation (produced in 2010) contained high amounts of PFHpA (20.6 and 28.4 ug/kg) and other 5- to 8-carbon chain PFCAs (12.3 and 5.8 ug/kg) Both insulations were produced by a company manufacturing environmentally-friendly materials and are regularly used for the insulation of floors and walls in modern buildings and especially in low-energy houses. "

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/307629934_Screening_for_perfluoroalkyl_acids_in_consumer_products_building_materials_and_wastes

Nonstick cookware can have PFAS, look for those that are PFAS free. Also the well known dental floss brands likely have it, my food coop has several PFAS free flosses to choose from. Desert Essence is one I like.

Do house wraps have PFAS in them? It seems like it would make sense if they did since the goal of waterproof vapor permeable is the same as in outdoor gear.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in