Governments are increasingly banning the use of plastic products, such as carryout bags, straws, utensils, and microbeads. The goal is to reduce the amount of plastic going into landfills and waterways. And the logic is that banning something should make it less abundant.

However, this logic falls short if people actually reuse those items instead of buying new ones. For example, so-called “single-use” plastic carryout bags can have a multitude of unseen second lives—as trash-bin liners, dog poop bags, and storage receptacles.

A U.K. government study calculated that a shopper would need to reuse a cotton carryout bag 131 times to reduce its global warming potential—its expected total contribution to climate change—below that of plastic carryout bags used once to carry newly purchased goods. To have less impact on the climate than plastic carryout bags also reused as trash bags, consumers would need to use the cotton bag 327 times.

My research has evaluated carryout bag regulations from many angles. In a recent study, I examined how plastic carryout bag bans in California have changed the types of bags people use at checkout, as well as these bans’ unintended impacts on consumer purchasing habits. My results showed that bag bans may not reduce total plastic usage if people begin purchasing trash bags to replace the carryout bags they were previously reusing for their garbage. As this finding shows, well-intended product bans can have unintended consequences.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

Plastic bag use in California

California provides a unique laboratory for studying plastic bag regulations. From 2007 through 2015, 139 California cities and counties implemented plastic carryout bag bans. This local momentum led to the first statewide plastic bag ban in the United States, voted into law on Nov. 8, 2016. Because these restrictions were adopted at different times across the state, I was able to compare bag usage at stores with bans to those without, while also accounting for potentially confounding factors, such as seasonal shopping patterns.

Using sales data from retail outlets, I found that bag bans in California reduced plastic carryout bag usage by 40 million lb. per year, but that this reduction was offset by a 12-million-lb. annual increase in trash bag sales. This meant that 30% of the plastic eliminated by the ban was coming back in the form of trash bags, which are thicker than typical plastic carryout bags.

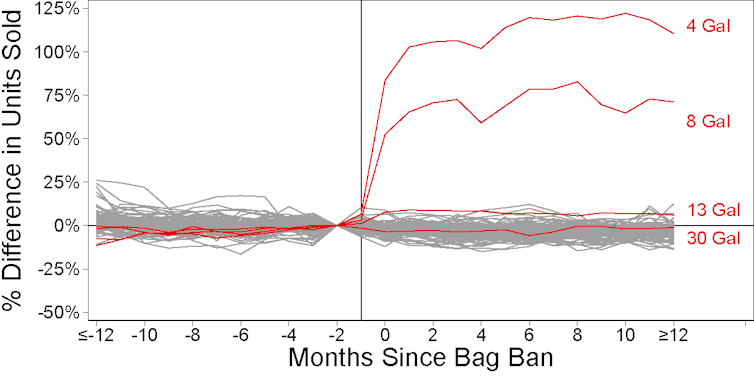

In particular, my results showed that bag bans caused sales of small (4- gal.), medium (8-gal.) and large (13-gal.) trash bags to increase by 120%, 64% and 6% respectively.

Disposable does not automatically mean single-use

Although plastic carryout bags are widely referred to as “single-use,” consumers don’t necessarily treat them that way. By comparing the reduction in plastic carryout bags used at checkout to the increase in trash bags sold, my results revealed that 12% to 22% of plastic carryout bags were reused in California as trash bags pre-ban. Each reuse avoided the manufacture and purchase of another plastic bag.

Moreover, my study underestimated reuse because it did not examine other ways in which people use plastic carryout bags, such as wrapping fragile items for shipping or storage instead of using plastic bubble wrap. Nor did it address increased use of reusable bags made of thicker plastic in place of disposable plastic bags.

The U.K. study did examine the impact of shifting to thicker reusable plastic bags. It found that if these thicker bags were not reused between 9 and 26 times, they would have a higher global warming potential than disposable plastic carryout bags reused as trash bags.

Who bears the burden?

Who were the people who reused plastic carryout bags pre-ban, and presumably bore the burden of buying trash bags post-ban? I found that bag reuse was higher for people who purchased pet items and baby items—in other words, who needed to collect and dispose of excrement. In 2017, nearly 6% of U.S. households had a child under 5 years old, 44% owned a dog, and 35% owned a cat.

I also found that plastic bag reuse was higher among people who shopped for bargains. Although reusing shopping bags as trash bags could be motivated by environmental concern, it also could be motivated by frugality. Interestingly, I did not find a correlation between plastic bag reuse and income or political leaning, but I did find a positive correlation with higher levels of education.

The case for fees instead of bans

Why didn’t policymakers foresee that bag bans could drive up trash bag sales? Policies typically miss the mark because policymakers either do not understand people’s current behavior or fail to anticipate how people will respond in a completely new situation.

Banning carryout bags illustrates the first problem. Before plastic bags were banned, there was little data on who reused plastic bags or how they reused them. California’s natural experiment revealed this information for other jurisdictions to improve upon.

In my view, policymakers who want to minimize plastic use should consider ways to help people who want to reuse disposable bags. One option would be to offer incentives for producing inexpensive, thin carryout bags specifically designed and marketed to be used first as carryout bags, then for trash. Such bags would need to sell for less than 9 cents per bag to be price-competitive with current 4-gal. trash bags. Ideally, they would be thin enough to contribute no more to climate change than traditional carryout bags.

Another route that some jurisdictions, including Washington, D.C., have implemented is adopting plastic bag fees instead of bans. This approach, which allows customers to continue using plastic carryout bags as trash bags for a small fee, has been shown to be as effective as bans in encouraging consumers to switch to reusable bags.

However, current bag fees have not promoted other uses for disposable carryout bags. These policies could be improved by educating customers about the environmental benefits of reusing disposable products. As a general rule, the more an object can be reused—even a disposable item—the better for the environment.![]()

Rebecca Taylor is a lecturer in economics at the University of Sydney. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

25 Comments

Can anyone point me to a facility that could convert used ripstop nylon or banner sign material to bags? Preferably in the western US, as shipping for production would most likely negate any ecological benefits, as well as become cost prohibitive on cheaper items.

Our town just implemented a ban and I think we're seeing something similar here. We have multi-use totes coming out of our ears now that are made with new material. I fly paragliders and also own a print shop. As flying and skydiving gear has a limited lifespan and banners are only displayed for a short time, I have access to a wealth of ripstop nylon and also banner sign material to repurpose and would love to recycle - preferably as a full side business, where part of the profits could be donated to ecological causes. Anyone have any sources for manufacturing these? Thanks!

Ripstop nylon is very common in backpacking gear, such as hammocks, sleeping bags, quilts, and tents/tarps (when silicon infused). If the ripstop is in good condition, and not too heavy (usually, less that 2 oz/yd is preferred), then there could be a market there, since hikers tend to be an environmentally conscious bunch. A lot of cottage industry too, so low barriers for market entry.

This article referenced recycling vinyl siding:

https://www.greenbuildingadvisor.com/article/recycling-vinyl-siding

With this map:

https://www.vinylinfo.org/recycling-directory/

While they themselves may not recycle it, they may know of other places that do.

Broken window fallacy strikes again. Will bureaucrats ever learn?

Plastics in the environment is a massive issue, and we have more than a century's worth of waste clogging landfills and worse - showing up in form of microplastics in almost every biome on earth, even at the bottom of the Mariana trench. They represent a massive threat to animal populations, and the situation gets worse every year.

The plastic bag bans are probably good on a whole, but have a lot of unintended consequences, as aptly laid out by this article, but have a bit of a feel-good legislation element to them. The problem is vast and complex. Some developing countries have poor waste stream management, while in developed countries, a lot of plastics pollution comes from surprising sources: washing synthetic clothing and tire wear and tear, for example. Here is a sobering report on plastics and microplastics by the IUCN: https://portals.iucn.org/library/sites/library/files/documents/2017-002.pdf

We have to make sure we don't pat ourselves on the back re: plastic bag bans and then go home. Every industry, including the building industry needs to look at its practices (reducing waste) and materials to mitigate this challenge. We are very focused on the carbon cost of things and efficiency (our most immediate risk), but there are other elements of being good stewards of the environment.

Ya I read an article a while back about microplastics finding their way into the food supply. It's the latest example of the Tragedy of the Commons. In this case The Commons is the worlds oceans. On way to combat that is via privatization but for a variety of reasons it could never happen and even if it did it would be certain that governments would make damn sure that obtaining relief from a favored polluting industry would be damn near impossible.

On a more local level imagine the uproar if the Feds prohibited trash from being exported out of the country or dumped in the ocean.

This article is pretty misleading. It states at the beginning that "The goal is to reduce the amount of plastic going into landfills and waterways", and proceed to demonstrate that... it works. According to the figures in the article, it cuts single-use plastic production by a net of 28 million pounds per year.

Sure, CO2 production is higher, but the goal of single-use bag bans is not to reduce CO2 production. The point is to reduce the amount of plastic ending up in landfills, and by the article's own account it seems to work.

That's not to say that reducing CO2 emissions isn't a good thing, but you would have a hard time arguing the relatively tiny decrease in global CO2 production from single-use plastic shopping bags is worth the tradeoff of the massive harm that they cause the environment in other ways. And, very notably, this article does not attempt to argue that!

Hell, last I checked, curbside plastic recycling generates more CO2 than virgin plastic production. Does that mean we should stop recycling plastics?

Aedi,

Q. "Last I checked, curbside plastic recycling generates more CO2 than virgin plastic production. Does that mean we should stop recycling plastics?"

A. Possibly.

Martin,

The good news is that "last I checked" was more than a decade ago. Data from 2011 indicates that even the worse curbside programs cut energy use and CO2 production by about a third. See Figure 3-6 here: https://plastics.americanchemistry.com/Education-Resources/Publications/Life-Cycle-Inventory-of-Postconsumer-HDPE-and-PET-Recycled-Resin.pdf

(edit: Dana provides a modern source in #11 with different figures that do show slightly higher CO2 emissions for curbside recycling. Either way, the scale is dwarfed by other sources of CO2 emissions).

As for the scale of emissions for reusable shopping bags, lets use the 28 million pounds saved -- for convenience, we'll translate that to 13,000 metric tons, because that is a common measure of carbon emissions. That means those plastic bags represent about 78,000 metric tons of CO2 (~6 kg CO2 per 1 kg plastic). Lets assume a patently absurd worst-case scenario: that everyone switches to cotton bags (which I think are the most carbon intensive kind) and never reuses them -- not even once! According to the article, that would generate 131x more CO2 than the virgin plastic bags, increasing California's total CO2 emissions by... 2%. Any vaguely realistic scenario results in a tiny fraction of that.

The carbon emissions caused by switching to multi-use bags are completely negligible, compared to things like transportation and energy production, and would be cancelled out my even a small efficiency gain in those areas. Using CO2 emissions as an argument against reusable bags serves only to muddy the waters, which as far as I can tell is usually the point.

"last I checked, curbside plastic recycling generates more CO2 than virgin plastic production"

Aedi, I don't doubt that's possible but I can't find an online resource to support your claim--can you provide one?

Michael,

As I mentioned in my reply to Martin, this hasn't been true for quite some time. See reply above. (edit: maybe I'm wrong, see Dana #11. Either way, the scale is dwarfed by other sources of CO2 emissions).

As an additional note, the subtitle of the article "Single-use bags often have many uses, so bans may not reduce overall use of plastic" is completely contradicted by evidence provided by the article, which clearly show a reduction in plastic production. What's up with that?

Do you believe in arithmetic? (I do, sucker than I am! :-) )

"Using sales data from retail outlets, I found that bag bans in California reduced plastic carryout bag usage by 40 million lb. per year, but that this reduction was offset by a 12-million-lb. annual increase in trash bag sales. "

Lessee, 40 million minus 12 million comes out to a net 28 million lb. reduction in plastic.

A 70% reduction in plastic for bags seems like a net win.

"My results showed that bag bans may not reduce total plastic usage if people begin purchasing trash bags to replace the carryout bags they were previously reusing for their garbage. "

But as reported Rebecca Taylor's results show that it in fact that a bag bans DOES reduce total plastic usage (by 70%!) despite increased purchases of trash bags to replace some of the carryout bags that were being re-used prior the ban.

It's all a moving target when human behavioral aspects are factored in, but the data show a reduction in plastic use with the ban, despite a theoretical possibility of increased plastic use.

Clearly there aren't 100% firm hard answers, but her data appear to support the thesis that a ban is beneficial if the goal is reducing plastic use.

Dana, that was indeed my conclusion. That's why I am so puzzled by the subtitle, which implies the opposite is true. It makes me very concerned about the motivations of the person writing the article.

Question for Martin and Aedi:

Which poses the greater threat, CO2 emissions or the harm to the environment by waste products from disposal of the plastics--bags in particular?

Also, Aedi, I'd like to read more from the source on CO2 generation from curbside plastic recycling--sounds interesting.

Antonio, you didn't ask me but I'll answer anyway--CO2 pollution is a far greater and more urgent threat than solid waste disposal. Both are serious issues, and problems with solid waste disposal are easier to see than global warming emissions are, but climate change is a much greater threat to life on earth.

Antonio,

I address the carbon points in my reply to Martin. As for waste products, the harm caused by these are hard to quantify. In landfills, the eventually plastics break down into toxic chemicals, but the bigger concert is the portion of plastic bags simply left in the environment. They are bad for wildlife, but how bad and on what scale is not well known. There is also the waste products generated in plastic manufacture to be considered (and the waste generated in the production of reusable bags).

The only reason I lean towards preventing land and water based pollution from single use plastics compared to the air pollution from reusable is because the latter is completely dwarfed in scale by other sources of CO2, whereas single use plastic bags are a fairly big and notably harmful source of plastics pollution -- though, I should note, is nowhere near a majority of plastic disposed of (again, leaks/illegal dumping by industry is far ahead of anything consumers do directly)

The emissions from recycling & processing used plastic only modestly exceed those of manufacturing more virgin stock polymer, and not NEARLY enough to make it environmentally rational to landfill or incinerate plastic after a single use.

From a popular press version:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/04/190415144004.htm

"The emissions reductions from eliminating the need for new plastic outweigh the slightly higher emissions that come from processing the scrap. Currently, 90.5% of plastic goes un-recycled worldwide, a figure calculated by UC Santa Barbara industrial ecologist Roland Geyer, which made statistic of the year for 2018. Clearly, we have plenty of room to improve."

More detail (see Chapter 6, figure 13)) :

https://www.ciel.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Plastic-and-Climate-FINAL-2019.pdf

Of course the best solution is to avoid using plastics in non-durable, single use applications.

I am the recycling ring-leader in our 3 person household, so I like to know all the details concerning environmental impact, life cycle, etc. Here is my experience.

I have switched to using and reusing the free store 20 liter paper bags instead of 'single use' 10 liter HDPE bags. Previously I used plastic and then returned them to the store recycling bin. My concern is that recycling is all show and the bags just go to landfill. Recently, some evidence from the media supports the lack of markets for recycled plastic bags.

Paper self stands for easy bagging and then folds flat in the car for storage. Store baggers tend to put many more items in paper than plastic, so it's probably no different from a materials standpoint. Granted, multiple paper bags generally require you to take the store kart to the vehicle for ease of use, whereas one might carry 10 plastic bags in both hands. When a paper bag tears or becomes unusable after 20-50 uses, then it will turn to flames in my metal charcoal chimney starter!

The UK Life Cycle Study assumes 'free' 20 liter HDPE store bags and that no one reuses paper bags. I guess if you don't have a vehicle, then paper might take a beating in the rain going home. They also assume a self-bagging type grocery stores with 5.88 items in HDPE bag, versus 7.43 in paper bag. Not really applicable in USA with 10 L HDPE bag stack in most stores (see article photo).

We do reuse the better (no air holes) 10 liter LDPE/HDPE store bags for cat litter, but purchase 49 liter tall kitchen bags (bulk roll- thin and cheap) for waste. Due to heavy recycling, the 32 gallon/121 liter garbage can is put to the curb every 3-4 weeks.

I'm not against longer lasting reusable bags, but one bad experience with cheap woven synthetic bags that fail after a year or two and end up as garbage.

More math. Getting groceries about once a week, 52 weeks a year, for 6.28 years. Yes, we have easily used our cotton bags 327 times. they're in fine shape and I'm sure we'll use them 327 more.

WOW, that's a lot of grocery shopping, I may have to start looking at the carbon foot print of those grocery delivery services. Seriously though, one truck (electric) driving around the neighborhood a couple times a week dropping off everyone's groceries makes a lot more sense than each individual driving to the store and then there could be some kind of container that's exchanged, no bags necessary.

Let's face it, there's almost certainly more of a footprint in the single use plastics, glass, and cardboard containing food inside the bag than there will ever be in the bag, but that's a whole other conversation.

Andy,

I'm not sure it's desirable to try and view all activities solely in terms of their energy footprints. We live in a rural area and do a once a week trip to town to shop. This morning we visited four stores and the library. That would be a lot of delivery trucks heading out our way. But more importantly for me, we also spoke with at least two dozen people in those stores - owners, employees and customers. Those are social interactions that forge relationships. The same is true in my professional life. The conversations I have at the contractor sales desk at the lumberyard are both social and informative. I'm not sure economic activity divorced from social interaction is that desirable, maybe because I don't see life as a problem to be solved.

I'm disturbed by the bogus reporting and conclusions drawn from already questionable data, such as equating a 70% reduction in plastic use to no reduction, as other people have already commented. I don't think anyone has mentioned that the 327:1 ratio quoted for cotton to single-use plastic bags assumes that 100% of single-use bags are each reused three times as liners. The 100% reuse of every bag is so far outside of any reported research as to be a fantasy. So is reusing every flimsy bag three times as a liner, before final disposal. My mother shops and eats modestly, saves every single-use plastic bag for recycling, and reuses all that she can for liners and pet waste disposal. She ends up with dozens of extra single-use bags that need to go to recycling. Both the article and the study from which it draws data don't mention that even a conservative shopper will end up with many more single-use bags than they can reuse.

Cotton bags, in my use, hold three to four times the volume of single-use bags. That has to be factored into the comparison with plastic bags, although the weight of groceries in each bag can be a factor for some people. But reducing the author's questionable 131:1 ratio by a factor of four, we are down to about 33:1.

I've read through the article, the summary of the UK report, and the detailed section of the report comparing the relative impact a cotton shopping bag to a single-use plastic bag. I can't deduce whether the study's 131:1 resource use ratio is comparing one cotton bag to one single-use plastic bag; to 131 single-use plastic bags; or to the number of single-use bags needed to transport the equivalent amount of groceries as a cotton bag in normal use. These numbers would be very different. Can anyone understand this aspect of the data given in the study?

Good point. Most cotton, or reusable plastic bags carry about three west coast plastic grocery bags worth of groceries, or about nine midwest plastic grocery bags worth (see my other comment for an explanation of that).

A big swath of the country could do a lot just by using 1/3 as many plastic bags at supermarket checkouts. I lived on the west coast for many years then in the chicago area for a few and it staggered me how many bags they would use to pack your groceries there. This seemed to be a very broad regional practice across many stores in the regions, even stores from the same chain (eg Target).

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in