Air source heat pumps are a great way to keep a home comfortable. On the cooling side, they’re exactly the same as an air conditioner. In heating mode, though, they have a limitation that other types of heating equipment don’t have. That is, the heating capacity of most air source heat pumps decreases as the outdoor temperature goes down. That’s not the Achilles’ heel of heat pumps I’m talking about, but it’s related.

If the heat pump can’t provide as much heat as the house needs, we just have to figure out how to get the extra heat we need. The most common way it’s done is to add electric resistance, or strip heat, to the system. When the heat pump isn’t quite carrying the load, it kicks on and adds extra BTUs to the air stream. And this is where the Achilles’ heel of heat pumps comes in. Let’s dive in.

Electric resistance vs. compressor heat

Electric resistance auxiliary heat is just a big toaster element that gets installed in the air stream of a heat pump. The photo above shows one I saw recently. It’s downstream of the coil because otherwise hot air would blow over the coil and cause it not to work.

Now, the next statement is going to drive some people crazy, but I’m gonna say it anyway: Electric resistance heat is 100 percent efficient. All of the electrical energy getting used there becomes heat. OK, a there might be a bit of light, noise, and vibration, but that all turns into heat, too.

And this will drive those people even crazier: By the same measure, a heat pump is about 300 percent efficient. That is, the amount of heat energy delivered to the home is about three times more than the electrical energy used to operate the heat pump. Yes, the efficiency of an air source heat pump decreases as the outdoor temperature drops, but it’s still more than 100 percent in all but the coldest weather.

The takeaway here is that you want to use the heat pump as much as you can and rely on the resistance heat only when necessary.

[For the curious, the reason talking about the efficiency of strip heat and heat pumps drives some people crazy is that it’s the wrong quantity. We really need to talk about coefficient of performance (COP), which is defined as the ratio of the amount of useful heating provided to the amount of energy used to provide that heat. So technically, I should say electric resistance has a COP of 1.00 and a heat pump has a COP of about 3.]

Incorrect thermostat advice

I’m not going to say much here because I’ve covered it in an article that you can read for a full explanation. Basically, though, the problem here is that some bad advice about how to set the mode for the heat pump keeps getting spread around.

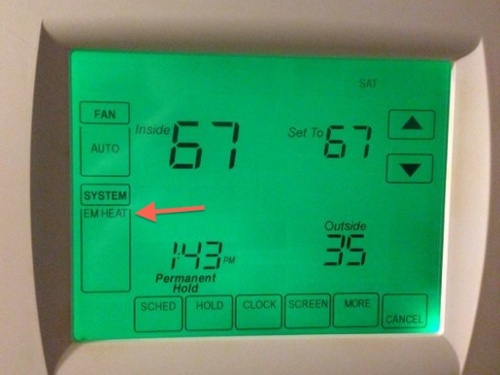

The thermostat for a heat pump gives you two modes for heating: Heat and Emergency Heat. When you choose Heat mode, it’s supposed to rely on the compressor for as much heat as it can provide, and then call on the strip heat when that’s not enough. It’s a way of providing just enough strip heat to keep the house comfortable and energy bills reasonable.

If you select Emergency Heat, you’ve just turned off a working compressor and now will get all of your heat from the electric resistance strips. That means you’ll be paying two to three times as much for that heat as if you were using the compressor plus the strip heat.

Incorrect settings or wiring

The goal in using strip heat is to use the compressor to provide as much heat as it can and then supplement with the strip heat when necessary. But whether that happens or not depends on the controls. One way to control the auxiliary heat is to base it on the difference between the thermostat setpoint and indoor temperature. If the gap is larger than the setting dictates—say, 2 °F (~1 °C)—the strip heat comes on to assist.

Another method is to have an outdoor temperature sensor. Then the installer sets the outdoor temperature that triggers the strip heat. If it’s set for 40 °F (4.5 °C), you’ll use more strip heat, most likely unnecessarily. If the system is sized correctly, the heat pump’s balance point should be about 30 °F (-1 °C) or maybe even lower.

Then there’s something called lockout. It’s an outdoor temperature setting at which the heat pump compressor is locked out. Generally, that should be used only when your auxiliary heat comes from a furnace. If you have electric resistance auxiliary heat, you’ll end up with higher bills, again unnecessarily.

Finally, it’s not that uncommon for the thermostats and auxiliary heat to be wired incorrectly. That can make the strips come on when they’re not needed. The worst case here is when they come on in cooling mode. Yes, that really happens.

Alternatives to electric resistance

One way to avoid having problems with electric resistance auxiliary heat is not to use it. No, you won’t freeze. You just need to have another way of getting supplemental heat when the outdoor temperature is below the balance point and emergency heat when the heat pump stops working.

Here are a few ways to do that:

- Cold-climate heat pump. Some heat pumps can maintain full capacity down to -5 °F (-20 °C) and still get about 80 percent at -15 °F (-26 °C). That’s usually the kind that lets you avoid strip heat, but it only avoids the need for supplemental heat. You still need a plan for emergency heat.

- Furnace as backup. This one’s not just supplemental heat. It’s replacement heat because the furnace and heat pump don’t run at the same time. At the switchover temperature, the heat pump goes off and the furnace kicks on. This is called a dual-fuel system.

- Hydronic coil. Instead of having strip heat after the heat pump coil, you could have a hydronic coil providing the supplemental or emergency heat.

- Redundancy. If you have multiple indoor units to heat your home, you can still get heat even if one unit goes out. This helps more with cases where you need emergency heat, but it may help with the need for supplemental heat, too, if you have excess capacity in some zones that can help heat other areas. But you have to have multiple outdoor units for this to work. (See my article on redundancy for more.)

- Space heaters. For homes with low loads, a space heater or two may be a perfectly adequate source of auxiliary heat. Gary Nelson heats his Minneapolis home with a heat pump that has no auxiliary heat. He told me that if it’s so cold the heat pump can’t keep up, he can get the extra heat he needs with a space heater…or even by baking cookies.

- Woodstove. This one’s controversial in the world of building science, but it’s what I’m planning to use as my source of emergency heat.

- Ground-coupled heat pump. I know I’ve focused on air-coupled heat pumps here, but another way to avoid electric resistance heat could be to go with a ground-coupled heat pump. They don’t lose heating capacity the way an air-coupled heat pump does when the outdoor air temperature drops, but that’s not a guarantee you won’t need some kind of auxiliary heat. (More here.)

Electric resistance is often necessary

Every house and every project is different. Some people (like me) are OK with undersizing their heat pumps and letting the indoor temperature drop below the setpoint during extreme weather. Others want to be able to keep the house at 75 °F (24 °C) on the coldest days. Then there’s the matching of the equipment capacity to the loads, the type of equipment selected, and the climate zone. All these things go into deciding what to do about auxiliary heat.

In our HVAC design projects at Energy Vanguard, probably half or more of our projects have strip heat. It’s the easiest way to assure homeowners that they’ll be covered when it’s cold outdoors or when the heat pump breaks.

Final thoughts

Electric resistance heat isn’t a bad thing to be avoided at all costs. It’s fine to install it. You just want to make sure it’s called on only when necessary.

Achilles, you probably know, was quite the accomplished warrior. But he had that one weak spot on the heel his mother held when she dipped him into the river Styx. Likewise, heat pumps are great at doing their job, but the Achilles’ of heat pumps is getting set up improperly with electric resistance auxiliary heat. It’s a weak spot that can cause higher upfront cost (especially if you need a panel upgrade) and higher electricity bills.

________________________________________________________________________

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and is the author of a bestselling book on building science. He also writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. For more updates, you can subscribe to Energy Vanguard’s weekly newsletter and follow him on LinkedIn. Images courtesy of author.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

13 Comments

I had a 6-head ductless heat pump system installed in my 1894 Denver home this summer. The house is not air-sealed and not well-insulated. We really appreciate turning on the cooling when and where we need it. We will see how far this high-efficiency cold-weather Mitsubishi unit gets us in the winter. I'm hoping just a few spot electric space heaters will be enough, but we will likely need to rely on our aging gas boiler and radiators for the coldest month or two (which will require an expensive repair to get running again). We will look to install solar on our roof next summer to help zero out our larger summer and winter electrical loads.

"Fabric first" or envelope improvements first is still my recommendation whenever possible, but the realities of my family and house don't make major envelope upgrades possible right now. This article really helps existing homeowners set expectations and plan for reasonable supplemental / emergency heat sources. Cheers Dr. Bailes!

When our new house was built in 2010-11, the heating system installed was GSHP. This was a good choice for us, as the house is superinsulated (CZ 6 - central NH), and the heap pump was the smallest size available at the time (2 ton), with actual capacity of about 25.4K BTU/hr. The calculated design heat load was 22K BTU/hr, or about 6.4 KW, so there already was around 15% capacity over what I had calculated. The ductwork was zoned, so there was a zone board for control purposes, and it allowed for two levels of auxiliary electrical strip heat. I ordered the heat pump with the minimum 5 KW of auxiliary heat, mainly for backup should the heat pump fail.

I wanted some provision for a little extra heat in extreme cold conditions in case the load calculation fell a bit short of reality, but I didn't want the zone board to engage a whopping 5 KW boost in heat output if all I needed was a smaller amount for a really cold night. What I did was to buy a 1KW strip separately and mount it in the air discharge duct right above the heat pump unit, with a little trap door for access. I set up the zone board to turn on first the 1 KW strip. Then, if the total output still couldn't keep up with heat losses, the board would engage the second (5 KW) level.

As things turned out, I have found that the heat pump keeps the house at temperature, even when the outside air is well below the town's design minimum temperature (-3 F), and in just first stage, providing about 19K BTU/hr (5.6 KW). Thus the only purpose the strip heat now serves is emergency heat if the heat pump should fail. This happened only once so far, when the water flow valve failed after a few years. I replaced that with valve having a newer, better design.

Dick,

Nice to see you posting. I learned a lot from your build over the years.

I just wanted to flag some incorrect information in this article: Most modern heat pumps will run heat strips at the same time as the compressor, to minimize heat strip use. Note also that heat strips are usually sized to supplement the cold weather output of the heat pump rather than fill the entire heating requirement.

In contrast, for gas furnace backup where the heat pump will shut off, and the gas furnace is sized to provide the entire heat load.

adavidso: If you read the article carefully, you'll see that nowhere did I say what you're claiming is incorrect. For example, the second paragraph starts thus: "If the heat pump can’t provide as much heat as the house needs, we just have to figure out how to get the extra heat we need."

See my articles on heat pump thermal balance point for more on this:

A Simple Way to Calculate Heat Pump Balance Point

https://www.energyvanguard.com/blog/simple-way-calculate-heat-pump-balance-point

This is the incorrect part: "If you select Emergency Heat, you’ve just turned off a working compressor and now will get all of your heat from the electric resistance strips."

Emergency heat will run both in most all electric setups to get maximum output.

This is partly because the electric backup coil is after the heat exchanger in an all electric setup (to supplement) but in a gas backup the gas furnace is before the heat exchanger.

Gas and electric backup heat operate in fundamentally different ways.

adavidso: Please tell me which brands and models you think will run the compressor in emergency heat mode. As far as I can tell, they don't exist. If any heat pump did that, it would make the emergency heat mode identical to the heat mode, and thus superfluous.

Most central Fujitsu and Mitsubishi or Carrier. Almost all. There is no circuit capacity to spec full backup for electric in most homes.

Example to achieve 80 kbtu:

Electric will be 48kbtu heat pump + 32kbtu electric coil.

Gas will be 80kbtu furnace + 48kbtu heat pump.

This is how they are specified and sold.

*Edit maybe we are getting a bit confused on terminology "emergency heat" should only be used with a dual fuel system. "Auxiliary heat" is the term for all electric with backup electric coil. Auxiliary heat runs both system at the same time, emergency heat will cut the heat pump and run gas only.

Good explanation here: https://www.pointbayfuel.com/auxiliary-heat-vs-emergency-heat/

I am still a bit confused about the heat strips. I live in cold climate zone 5. The house is about 5 years old and is well insulated (external insulation) and pretty airtight. We have a Fujitsu cold climate ductless mini-split system with 2-heads. We have had several periods with nighttime lows around -15°F and the mini-split system has kept the house comfortably warm. Am I correct to understand that because this is ductless, then there would be no resistance strips in them? Also, have I just been lucky so far that I don't need a backup? Is the backup in case of a power outage or just when it goes below -15°F?

We are planning our new build in Sooke, B.C. Canada (pretty close to Seattle or Port Angeles). We are thinking central heat pump as main heat source, but a few strategic electric baseboard heaters as back-up. If our heat pump is set to 72 degrees, we would set the baseboards at maybe 65, so the heat pump will do its thing, and the baseboard resistance heater only comes on when really necessary.

Is this a decent plan?

Stephen,

I'm just up the road from you in Shirley. What you are proposing is pretty common here, often the result of people moving from a wood stove to a heat pump as their main source of heat, and almost every house had baseboards both as back up, and to even out the temperatures in remote rooms.

Partly why it works is that our climate is mild and our electricity rates so low. Perhaps not something purists would consider, but I've recommended it for houses around here a few times.

One variant you might consider is mounting plug in electric resistance wall heaters instead of baseboards, which can be moved around or put away when not needed.

Thank you, Malcolm

Are there backup resistance coils like this that are compatible with slim ducted heat pump units?

What pressure drop in IWC should one assume for such a part in a manual D (e.g., for a 12K unit with ~400 CFM)? I'm doing my own manual D, hence the question!

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in