Image Credit: U.S. Department of Energy

Image Credit: U.S. Department of Energy Sweeping windows provided lots of natural light inside the prototype house. The design team wanted the house to appeal to a broad swath of the market. [Photo: U.S. Department of Energy]

It looks like a cross between a classic roadside diner and an Airstream travel trailer, but in its day the Michigan Solar House Project was nothing if not cutting edge.

MiSo, as it’s called, was created by students at the University of Michigan and one of 18 entries in the 2005 Solar Decathlon competition sponsored by the U.S. Department of Energy. Like other entries in the biennial contest, the house was the result of intense effort by student designers and their faculty advisers, to say nothing of generous corporate donors.

Now, 12 years later, MiSo is for the first time about to become someone’s home. A Michigan couple who first saw the building at a 700-acre botanical garden not far from the University of Michigan campus entered the winning bid in an auction for the building last fall. Preparations are currently underway to move the house 170 miles to Evart, Michigan, where it will be ready for move-in by spring.

MiSo will, according to records kept by the Department of Energy, be the fourth member of the Class of 2005 to become a private residence. Many others have been moved to public spaces like college campuses where they are open for public tours or used for ongoing research.

In this case, the 660-square-foot solar-powered house will give Lisa and Matt Gunneson their start at what Lisa calls a “simple, self-sufficient kind of life.”

A house intended for mass production

MiSo didn’t win any awards in the 2005 competition —the University of Colorado was the overall winner that year — but its features put it far ahead of any production housing of the day, and still make it an unusually energy efficient building.

Students from the Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning wanted a design that could be mass-produced with less waste than conventionally built housing, and serve as a prototype for a more energy-conscious way of living, according to a summary of the project. John Beeson, a student and the project manager, said that the team wanted to produce a house where people would actually want to live — not turn off potential homeowners with a design that perhaps seemed like a “neat idea” but ultimately wasn’t livable.

The house followed “monocoque” design principles, similar to those for cars and airplanes, in which the external skin of the building supports the weight of the structure. Students chose aluminum for the outside of the building because it lasts a long time and can be recycled.

There were a variety of innovative features: enough windows to heat the house passively, photovoltaic panels on the roof, solar thermal panels connected to a radiant-floor distribution system, and an energy-recovery ventilator. It also included what designers called a “solar chimney,” an internal channel between the roof and walls with south-facing glass panels at the base. In the winter, warm air heated by the sun could be directed into the house for heat; in summer, the hot air was vented to the outside, helping to keep the building cool.

Batteries in the floor of the house stored excess energy from the solar panels, and the base of each of MiSo’s five modular sections was a trailer to make the building easy to move.

After the competition

The Solar Decathlon that year was held on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. After the event was over, MiSo went back to Michigan, where it spent the next two years in storage at the Willow Run airport in Ypsilanti. It was saved from indefinite incarceration by Harry Giles, a professor of architecture at the university, who won a grant from the National Science Foundation to study energy-efficient modular housing prototypes, according to the Department of Energy.

Giles used some of the grant to move the house to a spot at the university-managed Matthaei Botanical Gardens a few blocks from the Ann Arbor campus. The location, DOE said, was handy to both university researchers and the general public and Giles used the building to teach another generation of students.

That’s where the Gunnesons first saw the house. “We have an emotional connection to the MiSo as Matt and I had our first date at the Matthaei Botanical Gardens, and were married there in 2015,” Lisa told an interviewer. “When we heard the solar home was up for auction, we put in a bid.”

By then, there had been some changes to the original structure. Flooring had been replaced with tile because of water damage. A rain garden, porous paving stones and gardens had been added to better blend the house with its surroundings. But from the outside the building looked essentially the same. By last year, the botanical garden had decided it was time to put the building up for auction.

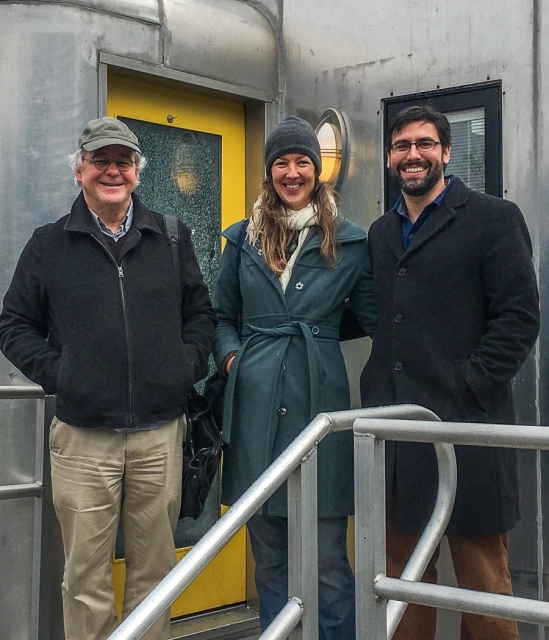

Giles contacted Doug Selby, the CEO of Meadowlark Design + Build in Ann Arbor, to ask whether he’d be interested in helping the new owners move and refurbish the house. Two designers at Meadowlark — Melissa Kennedy and Jennifer Hinesman — had worked on MiSo in 2005 as students, so there was a lot of internal enthusiasm for getting involved in a project that probably wasn’t going to add much to Meadowlark’s bottom line.

“It was quite obvious to us,” Selby said by telephone. “Who the heck is going to do this otherwise?”

Inside, the building had suffered some water leaks over the years, so there’s some mold to contend with. In addition, the interior cladding, which appears to be pressed wood panels, should be removed and probably replaced. Insulation needs an upgrade. Its current problems appear to stem from the way in which the five modular sections were re-assembled after the house was returned from Washington.

“When they put it back together the first time, they just caulked it, and caulk doesn’t last forever,” Selby said. In all, Selby expects the move and repairs will cost $30,000 to $40,000 on top of the $12,500 the couple paid for MiSo.

The building comes with 32 solar panels with a rated capacity of about 6 kilowatts. Selby said at the time MiSo was built, these standard panels, each with a rated capacity of 190 watts, came at a cost of $10 per watt. Now, he said, 280-watt panels are available for about $3 a watt — that’s how far solar technology has come.

Buildings with many uses

Decathlon entries find a variety of second lives once the competition ends, and program managers keep detailed records of where the buildings end up. In part, that’s to give new Solar Decathlon teams good background information on what’s come before them, said program manager Linda Silverman.

The Solar Decathlon dates to 2002, with biennial competitions beginning in 2005, with similar competitions springing up in Europe, China, Africa, and Latin America. Since its inception, some 130 teams here have participated, so there are plenty of second lives for the program to keep track of.

According to Silverman, Decathlon entries often become housing for faculty and students or learning labs about energy-efficient building on college campuses. One now houses a park ranger at the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve near Stanford University. Another serves as transitional housing for military veterans who have suffered traumatic brain injury; an entry from an Austrian team was designed to float on that country’s Blue Lagoon. Missouri Science and Technology, a frequent participant in the competition, has assembled its entries into a solar village where students and faculty can live.

“This is a big endeavor by the schools,” Silverman said. “They tend to have ideas about where they want the houses to go afterwards. But where they end up after the competition, or within a year or two of the competition, could be different in five years.”

Student teams not only have to design and build the houses, but figure out how to get them to the competition site, dismantle them after the competition is over, and get them back to campus.

The cost of a project for a U.S. team can range from $300,000 to $1.5 million, she said, with the money coming from corporate sponsors as well as the universities themselves.

“I think it’s the most unique experience you could possibly have because it’s so intense,” she said. It’s such a real world type of experience, and the students are just so committed.”

The 2017 Solar Decathlon takes place on October 5 through 15 in Denver. Thirteen teams — two of them representing overseas universities — will compete. For the first time, each team that successfully builds a house will get at least $100,000 for their efforts; top finishers will get “significantly more.”

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

2 Comments

Scott

Fascinating. Thanks.

Malcolm

Thank you.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in