Image Credit: Brute Force Collaborative

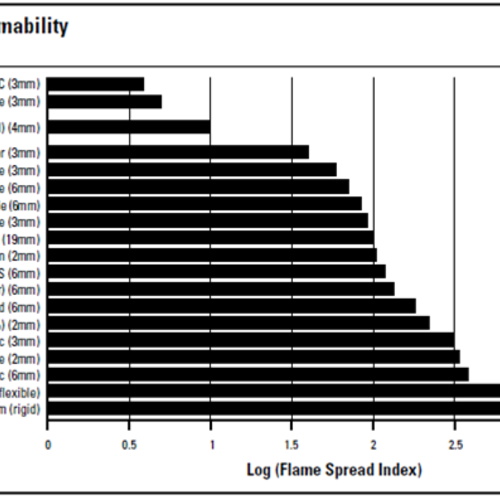

Image Credit: Brute Force Collaborative This graph shows specific space heat demand across different cities by heating degree days (HDD). The blue line is Katrin Klingenberg’s house modeled in CPHC training and migrated to North American cities; the red is Katrin’s house migrated through Europe. For comparative HDD ranges, the EU numbers trend significantly higher than North America.

Image Credit: Mike Eliason

By Mike Eliason

To preface: these thoughts are my own and draw from the Certified Passivhaus Consultant training, studying European Passivhaus projects (occasionally documented on our blog), modeling projects and dissecting PHPP with my brute force collaborative cohort, Aaron Yankauskas. They are in no way endorsed by PHIUS, PHnw, PHA or the PHI in Darmstadt…

Martin gave the kickoff address for the 2nd Passive House Northwest (PHnw) Spring Event. Unlike most kickoff addresses, his pointed out missteps of the North American Passivhaus movement. Amazingly, instead of deflating all 170 attendees, reactions were varied — agreement, disagreement and probably even a little rage! Attendees were discussing aspects of his address well beyond the meeting — a testament to issues with which many have struggled. There was a brief question and answer period, but no one successfully challenged Martin.

After the event, I was cornered by Martin to discuss my thoughts. Unfortunately (or perhaps fortunately…) my carpool was antsy to leave, so we weren’t able to get into as deep and fruitful a discussion as warranted. However, Martin has generously permitted me to address my thoughts on his thesis for the benefit of GBA. What follows are the central themes of his address and my own “musings of a design geek” for each. Like everyone at the meeting, I’ll probably be highly unsuccessful in challenging Martin, but appreciate the opportunity to expand the dialogue.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

Martin began his address with what he likes about Passivhaus: that it stands on the shoulders of North American giants, sets a high bar for airtightness and has created a significant buzz that “energy nerds” haven’t seen in a long time (or maybe ever). He then proceeded down his list…

Misstep #1: “Passive” is a problematic term and the direct translation “Passive House” is confusing

Passivhäuser (Passive Houses) employ active mechanical ventilation and require active heating components (albeit very small). If comfortable with a lower setpoint, throwing a dinner party or borrowing the neighborhood kids — it’s entirely possible to forgo any active heating and live in an entirely passively heated house. The term isn’t completely accurate, but at this point changing the terminology would only create additional problems.

I abhor the direct translation of Passivhaus! Whenever I talk to someone about Passive House (Passivhaus) – it devolves into a discussion of something tried in the ’70s, or a semantic argument with passive solar house designers. Every Passivhaus consultant knows this story, and that alone should warrant reconsideration. In German, Haus is slightly more nuanced than House — and non-residential buildings offer greater energy savings than residential projects. Plus, we don’t call the Volkswagen the Public’s wagon (although we happily obliterate Köln as Cologne!).

Misstep #2: Häuser ohne Heizung (houses without heating) is a false statement

There has been a lot of inconsistency in the way Passivhaus projects have been represented online and in print – though this isn’t the fault of the PHI, and I think there are other contributing factors. First, I believe this is another case where direct translation fails – Heizung could mean radiator and Passivhäuser simply don’t need them. Second, many Passivhaus owners just never utilize their heating systems. However, most require some degree of space heating, and it would certainly be better if consultants were honest about this and persistent in correcting media errors.

Misstep #3: Space heat delivered through ventilation duct

There is no requirement for space heating to be delivered through the ventilation duct – though this was the classic definition, which was apparently altered to appease the Scandinavians. If towel warmers, localized radiant heating or mini-splits are preferable to deliver space heating – they’re all acceptable forms. I’m not an engineer, but am really drawn to the decoupling of ventilation and heating as championed by Kiel Moe and Transsolar.

Misstep #4: 15 kWh/m²a (4.75 kBTU/ft²a) is too difficult and arbitrary

As was relayed to me recently, the 15kWh/m²a heating limit is the point when traditional heating systems could be eliminated and the cost of implementing Passivhaus became affordable. This limit wasn’t arbitrary for central European climates at the creation of the Passivhaus standards, but that point on Dr. Feist’s graph may shift in North America. After dissecting PHPP — that limit could very well be lower compared to Europe.

The argument that achieving the specific space heating demand is too difficult rings hollow. By keeping the standard difficult, it will push product innovation, designer innovation and maybe cause people to rethink whether building single family homes makes sense in certain climates. Who wants to wait 10 years for North American manufacturers to catch up to where E.U. manufacturers are now?!?

Regarding the extreme R-values — there are only a handful of built Passivhäuser in North America, and several were shoehorned through PHPP after being designed, resulting in absurdly high R-values. Basing the difficulty of achieving the specific space heating demand on these first projects is a biased sample. One of the pursuits of brute force collaborative is the utilization of normalized wall assemblies to meet Passivhaus. This means compactness, glazing, orientation, opening sizes, etc. are constantly being tested to ensure R-100 assemblies are only needed in Fairbanks. Don’t ask me why other people don’t work this way – we just enjoy geeking out with PHPP.

Over the last year, I’ve been combing European Passivhaus projects and have yet to find an envelope assembly greater than R-80 — even with climbing huts high in the Alps or smaller houses in regions that get little sun. PHPP consistently shows that it’s actually easier to achieve Passivhaus in the United States. Figure 2 (see below) shows the resulting specific space heat demand across different cities by HDD. The blue line is Katrin’s house modeled in CPHC training and migrated to North American cities; the red is Katrin’s house migrated through Europe. For comparative HDD ranges, the EU numbers trend significantly higher than North America.

What this says to me is designers and consultants in North America need to get creative and test the limits of PHPP. European designers don’t seem to have this problem, even though they are at a solar disadvantage. To further illustrate my point, the Österrichhaus in Whistler, B.C. (HDD: 8,000+) has no envelope assembly higher than R-54. That speaks volumes on how an integrated and oft-tested approach makes a significant difference.

Misstep #5: There is a lack of cost-effective feedback loops within PHPP, so Passivhaus designers just keep adding insulation — even if it’s beyond the cost of photovoltaics

Yes, there are people building excessive assemblies. Strangely, they would rather add insulation to their PHPP model than evaluate if the form, windows, openings or orientation need to be adjusted – even if doing the latter optimizes their assemblies. I don’t think this is a Passivhaus misstep, but a user one – PHPP is simply a spreadsheet and adding additional pages is not difficult. We’ve already seen ‘control panels’ allowing rapid study of assemblies and form. Much like the proliferation of cell phone applications – I imagine (hope?) we’ll soon see PHApps (Passivhaus Applications) – PHPP add ons for rapid testing, cost analysis, etc. Additionally, any designer could do a quick takeoff and check against cost of photovoltaics at any point along the way if so motivated.

Regarding insulation versus the cost of PVs — it seems PHPP doesn’t reward the use of grid-tied photovoltaics because this still leads to CO2 emissions through transmission losses over the course of the year. This can be seen in the energy utilization factors counted against the 120 kWh/m²a max. The specific primary energy demand is really a metric for reducing CO2 emissions of the building to levels agreed upon at the 1992 Earth Summit. To take this a step further — our interest lies in adding PVs that exceed net zero, resulting in carbon reducing/plusenergie buildings.

Misstep #6: Small house penalty

On the “difficult to achieve”-iness of really small homes: I believe Alex Boetzel summed it up best: the German mindset regarding the difficulty with small houses is maybe you should build a multifamily house instead. There is a lot of truth to that — and maintaining the difficult standard might force the owner to determine if that is really the most efficient use of resources. We already know that EUI (Energy Use Intensity) is a decent metric for comparative analysis of non-residential typologies and that it’s horrible for residential ones. Martin mentioned a preference for per person energy limits — which actually makes sense, but seems very difficult to enforce and may cause issues for growing families. In training, we were told that houses over 4,000 sf would get the Mantle treatment (*) — although on a certain level, I believe this should apply to second and/or rural homes as well, and maybe that asterisk should be closer to 3,200 sf.

Misstep #7: The standard doesn’t distinguish between energy sources

I agree up to a point, however PHPP does distinguish between energy sources for source energy (there are utilization factors for electricity/pellet/natural gas/etc) — it just doesn’t offer a “credit” for utilization of PV or wind. And again, this speaks more to the 120 kWh/m²a as a CO2 limit than anything else.

Misstep #8: Change the standard for North America like was done in Austria

Martin stated the Austrian government changed the standard, although with my broken German it appears this is only partially correct. In Austria, there are two routes to Passivhaus certification, through the Passivhaus Institut, or through a state run program which appears slightly harder than the first route. For the state-run option, the project needs to meet 10 kWh/m²a based on bruttogrossflaeche (gross square footage) instead of the PHI’s 15 kWh/m²a, based on Treated Floor Area. I’ve yet to see a house with that large a difference between the two reference areas.

Martin also advocates for climate specific standards – and when cornered, I jokingly stated, “the standards are climate specific – it just so happens that the standard is the same across all climates!” Semantics… Sure. But it’s also because I believe given the right orientation, envelope, designer, etc. – it is possible to achieve the specific space heating demand in Minneapolis, Vermont or Miami – without needing an assembly over R-70. The Bagley Nature Center in Duluth came pretty close with an R-85 roof. It even utilized North American windows and Cardinal 179’s triple pane — I would love to use this glass, Cardinal just needs to improve the U-value and SHGC by about 10%. Changing the standard to be easier in colder climates would effectively be a bonus for living in a location that requires more energy – and given our research, that’s not something I believe to be necessary.

Fervent discussions continue

In the end, everyone was (is) discussing Martin’s address with fervor — and it was stimulating to talk to those that agreed or disagreed and determine why. A lot of the things Martin and others see as issues or missteps — I believe to be misconceptions. I think as we become more familiar with the nuances of PHPP, a lot of these issues will sort themselves out. And hopefully, Aaron and I will have the opportunity to show that in the near future. If we do, you’ll find it on our blog.

Read Martin Holladay’s address: Are Passivhaus Requirements Logical or Arbitrary?

8 Comments

Demand creates innovation.

Having also attended the Passive House Northwest Conference (PHnw), I also felt the electricity in the air (happily for Martin it was from a renewable resource.)

Frankly, to be challenged on potential Passivhaus "mis-steps" at a Passivhaus Conference, was to me at first, worrisome ( I've put so much effort into PH!) and then exciting.

What I like about Passivhaus is what I like about all low energy building. It creates a dialog and raises the bar. It calls for new quality levels in both the envelop, and therefore, the components that go into it. If higher quality products are needed, are available in Europe but are not available here... Obviously the supply side of our building industry needs to grow. The demand for higher quality products is exactly what the supply industry needs to for it's own "recovery".

Creating demand does, in fact, create opportunities to design and manufacture high quality products in North America. None of this will happen without designers pushing the requirements!

What a great article. I love

What a great article. I love Martin's intelligent critiques of the PH standard, and here comes an equally intelligent response.

I especially like the term 'shoehorned' I shall steal it and use it as my own......

I have seen it on this site, people who have a whole concept of a house and want to add efficiency to it like they were adding a swimming pool...............

Thumbs up on Misstep #6

Small houses in cold climates should probably not be detached. Huddle together for warmth.

I agree...

The two articles by Martin and Mike are fantastic, and clearly illuminate the issues at the forefront of the passive house movement. Thank you Mike for picking up the gauntlet, and Martin, thanks for throwing it. Let's keep it up!

Chris Briley, Architect

Good discussion

I'd just add that I think #7 is not a misstep at all. Indeed I argue that biomass should not get the current low primary energy rating that it currently enjoys in PHPP but should be considered the same as other solid fuel.

As you say Mike, electricity is penalised in terms of primary energy factor.

I don't think that renewable electricity generation should be allowed to offset building energy use when judging the building efficiency. If PV generated electricity is not used in the building then it will be available for someone else. Separating generation and consumption avoids some paradoxes. A Hummer is no less benign if it is run on recycled cooking fat (imagine the perfect pollution free biofuel for the sake of argument). It's still guzzling a limited resource.

If you imagine a net zero energy building with PV and then add a gas boiler the building emissions go up but the country/planet emissions go down as electricity that was used for heat displaces 3 units of gas at the power station in exchange for one unit of gas burnt in the boiler.

I agree that if insulation is starting to cost more than PV something is wrong with the design. However the Passivhaus buildings I am working on (3 schools, 2 housing developments) all have similar insulation thickness to typical UK low energy buildings. The changes have been in form, fenestration, thermal bridge details, airtightness etc. Apart form the addition of mechanical ventilation and an extra layer of glass, most changes have reduced costs for example reducing heat loss area and optimising glazing sizes.

Response to Nick Grant

Nick,

You wrote, "I agree that if insulation is starting to cost more than PV something is wrong with the design." Unfortunately, that flaw exists in every single cold-climate Passivhaus that has been built in the U.S.

Response to Martin

Martin, we might be at cross purposes. It is possible that if you look at the incremental advantage of each final inch of underfloor insulation then the benefit might seem small if examined in isolation. I have not done this. What I have done is help design buildings that don't cost more than non Passivhaus ones. Undrslab we generally have 250-300mm of EPS. Beyond this it is easier to find savings elsewhere.

Generally we find that under-slab insulation thickness is not a good indicator of build cost, there are so many other places to waste money.

However dropping to what might be judged an economic level for one element may mean that surface temperatures are low and moisture or comfort could be a risk. Similarly I have never worried about the payback on warm edge triple glazing as I want to avoid condensation and the cold feeling.

However I do know of small PH dwellings in the UK that went over the top (IMHO) on the under-slab insulation in order to scrape through the PH target in a cold and cloudy climate zone in a shaded valley.

Presumably thickening the roof and walls would have been a planning issue as well as requiring non standard I beams etc - hence add another layer of foam.

This is an issue as that last couple of kWh can be hard to win in a small building in a miserable place - perhaps with the best views of grey hills and driving rain to the North. I'd still advocate AIMING for PH 15kWh/(m2.a) annual energy demand but might advise the client to settle for 18 or 20 or whatever seems to be making sense in terms of building design.

This is a problem in terms of marketing, 16 is a fail. Not an issue if all that is needed is a little more design effort but a big problem if it means much more South glazing than needed for light or much more insulation.

The problem with simply relaxing and adopting Passivhaus components and typical regional PH R values without the rigour of the PH approach is that you quickly end up at 40-100 kWh/m2.a. We see this when presented with a design that has planning but the client then decides to go for PH. Sometimes no amount of insulation and fancy glass will get even close. This is not a problem with PH, it is a problem with the laws of physics.

That the target is a challenge means that we have to tweak areas, glazing etc. It feels to me like testing a structure with a proof load. If my design is at 20kWh/(m2.a) I don't slap on more insulation as that means a long discussion with the QS and Architect, easier to look for changes that will reduce costs.

For the record, whilst I appreciate the historic reason for the target and do feel that it is about right, for my own projects I'm not an advocate of heating with the ventilation air. Among friends I even go as far as demonstrating that by tweaking assumptions the peak power definition can vary by a factor of 4. However I am still an advocate of the PH approach and of setting the bar at 15kWh/(m2.a). As someone said, if you don't stand for something, you will fall for anything.

As Mike says, whilst PHPP does not include automatic cost effectiveness feedback it is an ideal tool for exploring this as you can see where the gains and losses are.

Sorry this is a bit long. It would be lovely for the rest of the world if you guys used International units. I love feet and inches but can't get my head around your strange mix of energy related units :-)

Good Criticism is a Proof Load for the PH Concept

I am new to Passiv Haus and Low energy design and so many of Martin's comments were revelation's to me. How much faster we can evolve excellent designs appropriate to climate and budget by appreciating reasoned and informed criticism. I am delighted with the civilized tone of the discussion. I do agree with Nick that setting the bar at some value is important. Here in California the envelope mesures can be achieved with relatively modest insulation leves. The discussion is around the Air tightness requirements since the vapor pressure and condensation concerns are also less

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in