The past 2-1/2 years of the COVID pandemic have put a big spotlight on indoor air quality (IAQ) and the spread of infectious disease. I’ve been writing about various aspects of indoor air quality since I started this blog in 2010, so a lot of this wasn’t new to me. Still, I’ve learned some new things, had others reinforced, and generally feel like I have a more complete view of the subject than I did before 2020. Here’s my big picture view of IAQ now along with an example of how it was put into action at a conference I attended last month.

Good IAQ advice

1. COVID is airborne. If you’re still wiping down groceries, washing your hands obsessively, or hiding behind plexiglass, you’re not doing the most effective things to prevent COVID or other infectious diseases. Some people call those things hygiene theater. The problem is mainly particles that float in the air for hours (aerosols), not droplets that fall quickly.

2. The best method to avoid COVID is to stay away from people who have it. That’s source control. The COVID protocols that relied on testing were based on this method. You test positive; you can’t get in.

3. If someone with COVID is in a room with you but they’re wearing an effective mask (KN95 or N95 worn properly), that’s source control and filtration.

4. If you filter the air with MERV-13 filters or better to remove particulate matter, your exposure is reduced if someone is in the room with COVID and not wearing a mask.

5. By bringing clean outdoor air into a building and mixing it with indoor air, you’re diluting any pollutants in the indoor air. That’s ventilation.

6. Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI) is another proven air-cleaning method. But the key is that they must be properly engineered. If not, they may be ineffective or even destructive. To deactivate viruses in the air stream with an in-duct UV lamp, the power level has to be high enough for the air flow rate. And if the UV hits vulnerable materials, as is the case with some filters, it can damage them. This technology is best in hospitals and other buildings with a lot of people.

7. Carbon dioxide can be an effective way to monitor how much dilution is happening with ventilation air. With masks and good filtration of the indoor air, however, you can have high CO2 levels and little spread of infectious disease. Monitoring CO2 is only one part of getting clean indoor air.

8. Additive air cleaners may not make the air any cleaner. They may also do harm. There are no standards governing how they’re tested except for ozone emission. It’s best to avoid them.

9. Control the humidity. Neither too high nor too low is good. We’ve known for a long time that humidity affects indoor air quality. Now Stephanie H. Taylor, MD and some others say that keeping the relative humidity between 40 and 60% can reduce the spread of infectious disease. There’s still some debate about that, though. (See this paper from the journal Nature.) One thing to be aware of with keeping the relative humidity higher is that you must have a building enclosure that can take it in a cold climate. Otherwise, you can rot a building and even destroy it, as they did at Harvard.

An example from a conference

At the 2022 Westford Symposium on Building Science, also known as Building Science Summer Camp, we had a three-day conference with about 400 people. Three of the four sessions on the first day were on the topic of indoor air quality and the spread of infectious disease, including my presentation on the Corsi-Rosenthal DIY box fan air cleaner. And we practiced what we preached.

Professor Bill Bahnfleth spoke on buildings and infection control and evaluated the layered approach to IAQ at the event. It included:

- Upgrading the filtration in the room to MERV-13

- Increasing the mechanical ventilation with outdoor air

- Using three Corsi-Rosenthal boxes

- Irradiating the air with four upper-room ultraviolet germicidal irradiation lamps (one shown above)

- Some people (I was one) wearing masks

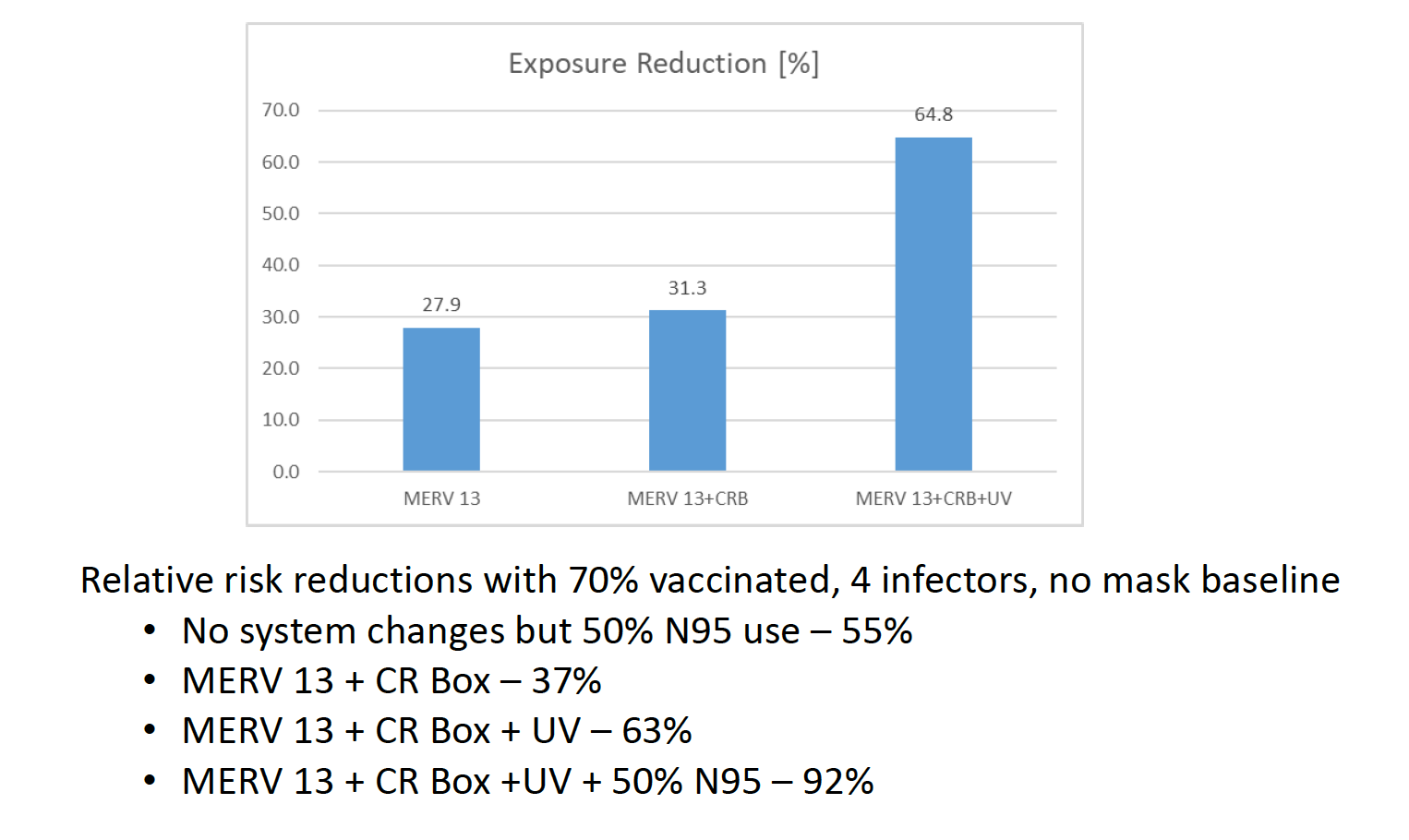

Below is the slide showing Bahnfleth’s calculation of the exposure reduction due to this layered approach.

Based on his calculations, we had an overall exposure reduction in the conference room of about 63%. If half the people in the room had been wearing masks, it would have been over 90%. The actual mask-wearing rate was less than 20%.

Of course, this is one example and incomplete anecdotal evidence, but there’s only one case of someone getting COVID at the conference. He’s pretty sure he got it there, but not in the main conference room. He was in a meeting in a small room that didn’t have those protective measures mentioned above. It’s possible more people got it and didn’t report back, but one out of about 400 people is pretty good.

The bottom line is that the workhorses of good indoor air quality are source control, filtration, ventilation, and humidity control. Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation is appropriate in some settings but must be engineered properly.

________________________________________________________________________

Allison A. Bailes III, PhD is a speaker, writer, building science consultant, and the founder of Energy Vanguard in Decatur, Georgia. He has a doctorate in physics and writes the Energy Vanguard Blog. He also has written a book on building science. You can follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard. Photos courtesy of author.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

10 Comments

I appreciate what you're doing. Taking what is mostly considered "building science" and extending it to the realm of public health. It really is possible to make crowded public spaces safer with relatively accessible measures. Thanks for doing what you can to contribute to health and safety!

Great article Allison. I've been working extensively over the last few months on a heavily instrumented ventilation system (with MERV 13) inline and Co2 monitoring in the interest of increasing interior air quality. On the UV side of things, I can appreciate that the reduction in risk correlated to the UV use was a calculation and the slide presentation you linked does contain some of the findings in actual research.

I'm wondering if you can comment on the upper room UV, vs the type you'd find in some portable air cleaners. One report I reviewed suggested that air velocities in a cleaner, or duct would generally be too high for UV to be very effective. Is this why the upper facing room UV is being used? I'm also guessing here that these are UV-C lights, so would not product ozone, correct?

"I'm wondering if you can comment on the upper room UV, vs the type you'd find in some portable air cleaners. One report I reviewed suggested that air velocities in a cleaner, or duct would generally be too high for UV to be very effective. Is this why the upper facing room UV is being used? I'm also guessing here that these are UV-C lights, so would not product ozone, correct?"

For reference for folks who haven't looked at the slides: Bill Blanfleth's presentation covers upper room UV-C in slides 35 and 41-45.

https://www.buildingscience.com/sites/default/files/buildings_and_infection_control_-_before_during_and_after_covid_0.pdf

The study you're talking about is when you're cycling air through a ductwork system, and have an in-duct air cleaner... you need to match the "radiative flux" (how much you're zapping) with the airflow to be effective.

At Summer Camp, we don't "own" the room or the equipment, so trying to retrofit in-duct UV was a non-starter. Thus the temporary upper room UV lamps--so they will affect any air in the illuminated zone.

In case it's useful, I included a few shots of the upper room UV equipment that I took during Summer Camp. They were *extremely* careful about the "sight lines"--making sure that standing people would not "see" the UV-C, given the risk of eye damage from extended exposure.

Nice article. Some day I hope the HVAC community will become more like you and take seriously the types of efficient and sophisticated systems you design and advocate for. This will improve our health, and energy efficiency!

This article has me rethinking my plan to install single head wall hanging indoor mini split in two bedrooms (each a 6k Mitsubishi units); and instead install a single 9k ducted unit with a MERV 13 filter built in. The Fujitsu ducted units have higher pressure units so I will probably go with a Fujitsu 9k unit

Nick: It's possible to do MERV-13 filtration on low-static air handlers. I do it at my house with Mitsubishi units rated at 0.20 iwc TESP. You have to have a low-resistance duct system and properly-sized filters. Here's how I did it:

My Low Pressure-Drop, MERV-13 Filters

https://www.energyvanguard.com/blog/my-low-pressure-drop-merv-13-filters

Your article resurrects a question I've been contemplating off and on for some time, namely: how should one best integrate filtration and ventilation? In my case, I'm doing a full reno of an old bungalow, with heating and cooling provided by minisplits, and ventilation by an hrv with dedicated ducting. The hrv holds a modestly sized intake filter (which could be a high Merv unit), but is relying exclusively on the filtered fresh air from the hrv adequate? Would you suggest installing additional filtration? If so, how would you configure such a system? I expect that the small size of the hrv filter will create undesirable resistance for the hrv blower as the Merv count increases, so maybe the hrv isn't the best mechanism to provide whole house filtration? On the other hand, if some dedicated filtration system is installed in addition to the hrv, then these two systems would seem to be competing against one another - with the hrv continuously pumping all your freshly filtered air out of the house. What's the holistic view on all this?

user-6966471: Ventilation with outdoor air is a dilution method. The pollutants may stick around in your house longer if you rely only on ventilation. I recommend MERV-13 filtration, and you may be to retrofit your system to get it. You just need to increase the size of the filter. See these two articles:

The Path to Low Pressure Drop Across a High-MERV Filter

https://www.energyvanguard.com/blog/path-low-pressure-drop-across-high-merv-filter

How to Make a Good High-MERV Filter Even Better

https://www.energyvanguard.com/blog/how-to-make-good-high-merv-filter-better

Regarding your question about using both filtration and ventilation, there's no competition there. Yes, the ERV* will exhaust some of the air that's been filtered. The net result, though, is that your air will be cleaner.

* You probably want an ERV, not an HRV. See this article:

https://www.energyvanguard.com/blog/why-you-probably-need-an-erv-not-an-hrv/

Allison,

Thanks for this additional info. We settled on an hrv (on the basis of that article actually) since we are in the Pacific Northwest, and are packing 4 people into quite a small house.

I had considered making an expanded filter box inline on the hrv intake side, but am wondering whether the effort would be better spent on a dedicated filtration system instead. Have you come across any elegant solutions for filtration where there is no other duct system to piggyback on? Our minisplits are ductless, so per current plan only the only ducts in the house will be those for the hrv.

user-6966471: Sounds like an HRV is the right answer for you.

You could set up a small duct system just for circulating and filtering air.

I found the article on Green Building Advisor about a layered approach to indoor air quality very informative and practical. It emphasizes the importance of considering multiple factors to achieve better indoor air quality, which is crucial for our health and well-being. To complement these strategies, I would like to suggest checking out HibouAir (https://www.HibouAir.com) for a reliable indoor air quality monitor. HibouAir offers real-time monitoring of pollutants like PM2.5, PM10, CO, and CO2, helping you stay proactive in maintaining a healthy indoor environment. It's a valuable addition to any effort to improve indoor air quality.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in