Image Credit: Connecticut Coalition Against Crumbling Basements

Connecticut authorities continue to gather information about failing concrete foundations in hundreds and possibly thousands of homes in the eastern part of the state, but there is no financial relief in sight now for homeowners whose houses are essentially worthless.

In early November, state Attorney General George Jepsen released the results of a scientific investigation, concluding the mineral pyrrhotite in aggregate used to make concrete was a “contributing factor” to deteriorating foundations. But homeowners so far have been left high and dry by both the state and their insurance companies, in part because nothing in Connecticut state law regulates how much pyrrhotite concrete may legally contain.

The state’s Department of Consumer Protection, which is conducting its own investigation, says that it has received 399 formal complaints from homeowners. But the state doesn’t know how extensive the problem is and says the number of homes with ailing foundations could run into the thousands. There also are suggestions, so far unconfirmed, that commercial properties are affected.

“The scope of the problem is a little hard to determine for a series of reasons,” said Lora Rae Anderson, the department’s communications director. “Many thousands [of houses] is definitely probable. We obviously do not have a complaint from every single person who has this problem. “

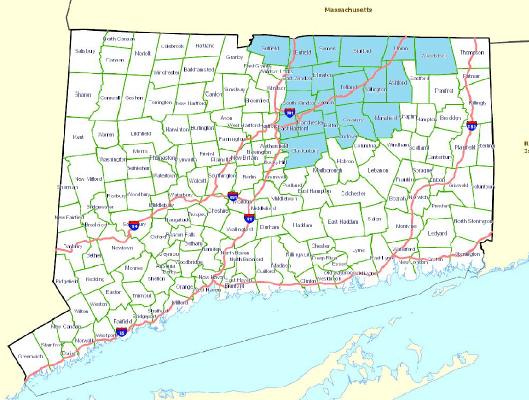

The concrete was made with aggregate mined in a quarry owned by the Becker Construction Company in Willington, Connecticut, and went into foundations in more than 20 communities beginning as early as 1983, according to the citizen group called Connecticut Coalition Against Crumbling Basements. Pyrrhotite can oxidize in the presence of water and lead to the formation of expansive secondary minerals, resulting first in a series of hairline cracks and eventually much more serious problems.

Problems may not show up for 20 years after the concrete has been placed. The coalition claims that the only way to fix the problem is by completely replacing the concrete — a process that includes jacking up the house, removing what’s there, and pouring new footings, walls, and slab.

A billion-dollar problem?

James Mahoney, the director at an engineering research center with expertise in transportation construction materials, said that the foundation of his 1998 Ellington home started showing hairline cracking this past spring. The discovery prompted him to begin researching the problem.

Drawing on data available from a variety of public records, Mahoney developed a model predicting that some 10,300 houses were built with concrete supplied by J.J. Mottes, a ready-mix supplier in Stafford Springs that used aggregate from the Becker quarry. Mahoney estimated that it would cost an average of $150,000 for each foundation/footing that had to be replaced.

“Based on the model inputs and assumptions outlined herein, the estimated cost to replace affected foundations for residential dwellings is well above $1 billion for the region; this only represents costs tallied for the 20 Connecticut municipalities that are currently known to be affected,” Mahoney’s report says. “This is likely a conservative cost estimate.

“There are very few ‘slow-motion disasters’ of a similar financial magnitude and duration that have occurred in the United States,” Mahoney’s study adds. His assessment does not include the number of foundations in a neighboring area of Massachusetts that might also be affected.

“Whether they’re all going to fail or not I don’t know,” Mahoney said in a telephone interview. “That’s literally the billion-dollar question.”

Connecticut Governor Dannell Malloy has placed the number of homes at risk much higher than that — more than 34,000 across the region, according to a report in the Hartford Courant.

The Massachusetts Attorney General’s office said it has received no complaints about either Becker

Construction or J.J. Mottes.

Some homeowners are keeping silent

The problem has cast an economic cloud over the region. Despite state efforts to protect those who file complaints about problems with insurers or banks, some homeowners have been reluctant to step forward.

“People are scared,” said coalition founder Tim Heim. “People don’t want to have the problem. People are ignoring they have the problem. People are scared if they have an equity loan and now their house has no value or no equity. Can the bank call that equity loan back? If your home has no value now and is worthless, do you fall into that [private mortgage] insurance category? There are numerous reasons why people aren’t acting on this, and I think the people who are ignoring it just don’t want to deal with the emotional burden and emotional stress it puts on a family.

“People have no idea of the emotional stress this puts on a family,” he continued. “You’re paying your mortgage every single month on a home you can’t sell.”

Heim lives in Willington, about a mile and half from the company that supplied the concrete for his 1994 home. Problems first showed up in the foundation late last spring. On a scale of 1 through 10, he describes the concrete failure as a 4, with both cosmetic and structural implications. The estimate for replacing the footings, foundation, and basement slab is almost $200,000.

Eleven of the 15 houses in his neighborhood have the problem, he said. A couple who lived across the street, both in their early 80s, put their house on the market for $450,000 and eventually sold it for $150,000, Heim said. A house down the street originally on the market for $250,000 sold for $112,000.

“It’s an absolute horror show here in eastern Connecticut,” Heim said. “You have no idea how tough it is. Once you’re told your home and biggest investment is worthless, it’s devastating. Absolutely devastating.”

The commercial connection

When the problem first came to light last year, Becker and J.J. Mottes agreed to stop selling concrete containing aggregate from the quarry for residential use until June 2017.

The puzzle was why the ban was limited to residential applications. “How can the concrete tell whether it’s in a residential or commercial application?” one reader commented in response to a GBA story posted in May.

An interview with William Neal, a professional engineer with a residential engineering business in Vernon, Conn., published in June by Engineering News- Record, suggested that the problem did extend beyond residential construction to a number of commercial projects.

Reached by telephone, Neal said that he has inspected some 800 buildings over the last six or seven years that have the pyrrhotite problem, including 300 condominiums.

Neal said, “We have a medical office building that has the problem. We have a strip mall that has the problem. We have the possibility of a couple of educational buildings that have the problem. I haven’t had an opportunity to look at it, but I’ve been told that one town hall has this problem. And I really don’t know why people are saying this doesn’t affect commercial buildings.”

Neal didn’t name the commercial buildings because of confidentiality concerns.

People may be assuming commercial buildings aren’t affected because the concrete used on commercial jobs is tested, Neal said.

“That is true, but it’s not the whole truth,” he added. “Commercial concrete is tested to make sure it has the required strength. … If this aggregate that causes the problem is present in the concrete, it does absolutely nothing to affect the strength of the concrete at the time it’s poured. It doesn’t affect the strength until sometime later when it starts to crack and deteriorate, which could be 15 or 20 or 25 years after it’s poured.

“It’s true that commercial concrete is tested, but what is not being said is that it’s not being tested for the properties that cause this problem. It’s totally irrelevant they test for strength.”

The state, however, says it doesn’t have any firm evidence that pyrrhotite-tainted concrete has caused problems beyond the residential arena.

“We’ve heard some claims of it and have definitely looked at some things, but it has not been a part of the scope of our investigation and our investigation hasn’t determined that’s true,” Anderson said. “We have definitely heard some claims of that, but none of those have come to fruition at this time.”

Likewise, the joint statement from the attorney general and the Department of Consumer Protection last year said, “To date, the state’s investigation has documented concrete deterioration of a comparable nature in a number of residential foundations but has not revealed similar evidence of failures of commercial or public building foundations.”

Even so, the statement urged commercial and public project managers to “exercise strict control and scrutiny” over the quality of concrete used in their projects.

No national standards on pyrrhotite

The scientific study released earlier this month suggests that the general problem of “sulfate attack” has been known for a century, but there are apparently no industry standards and no state or federal regulations that limit the amount of pyrrhotite that may legally be added to concrete.

“The only specification in the U.S. I’m aware of is in the New York State Department of Transportation, since either 2002 or 2003,” Mahoney said. “There is a 1% limit on pyrrhotite in their aggregate used for concrete. That’s the only specification I have found in the U.S.”

The American Concrete Institute (which describes itself as “a leading authority and resource worldwide” for standards and technical resources on concrete) didn’t respond to questions about a standard on pyrrhotite. “We don’t do the telephone,” said a person answering a call in the engineering department. A followup email sent to the department has so far not been answered.

Requests for aid are turned down

Thousands of homes in the province of Quebec have been affected by pyrrhotite-laced aggregate, prompting the government to set aside millions of dollars to help homeowners with repairs. But in Connecticut, aid has been slow in coming.

Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy last month called on the Federal Emergency Management Agency to set up a field office to help assess the extent of the problem, The Courant reported. The request was turned down earlier this month, although FEMA offered to make a “senior liaison available.” Malloy was told in April FEMA wouldn’t give the state emergency management money because the problem was a consumer protection issue and not a natural disaster.

Insurance companies have declined claims because the foundation problems don’t meet their definition of “collapse.” The New York Times said in an article that efforts to get insurance companies to contribute voluntarily to a fund that would help homeowners with repairs haven’t panned out.

A class-action lawsuit filed against insurance companies on behalf of some homeowners, plus the claims that individual homeowners have filed or are contemplating, may help over time. In the interim, Consumer Protection spokeswoman Anderson said, some state lawmakers are looking into different ways of providing financial help to homeowners.

There is still hope, she said, that some means of helping homeowners will be worked out.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

0 Comments

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in