Image Credit: Image #1: U.S. Geological Survey

Image Credit: Image #1: U.S. Geological Survey The Web Soil Survey (https://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov) starts with a satellite photo of the U.S. To get the ball rolling, you can either home in on the map or define your Area of Interest (AOI).

Image Credit: Image #2: USDA - Natural Resources Conservation Service This collection of early maps of Brattleboro, Vermont is like a lot of historic maps: chock full of land development details over the years. For more information, check out www.old-maps.com.

Image Credit: Image #3: www.Old-Maps.com The Library of Congress Chronicling America database allows you to explore digitized local newspapers by dates, locations, names of publications.

Image Credit: Image #4: Library of Congress This checklist is from a book by Max Schwartz, Basic Engineering for Builders.

Image Credit: Image #5: Basic Engineering for Builders by Max Schwartz

When we bought our home (built in 1907), I called in a favor from an electrician friend of mine to upgrade the 60-amp to a 100-amp service. Having worked together in New Hampshire where many of our projects were on sites full of ledge, he smirked when he told me: “Here, you go try and drive this 12-foot copper grounding rod.”

No more than 10 minutes later I came in and said, “How much of the rod should remain above grade?” It turns out our home, right in the middle of a steep, shaley, ledgey, slope, must have been built on a ton of free-draining fill, making our basement dry and that rod a piece of cake to drive nearly 12 feet into the ground.

But for both new construction and existing homes, isn’t there a better way to figure out just what soil, rock, and water challenges your site will pose?

Actually, there are three great online resources and a couple of others that take just about all the chance and guesswork out of determining site conditions.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

Web Soil Survey

Being originally trained as an agronomist, I first went to our Vermont soil specialist, Thomas Villars. He sent me a Word document, “How Get Site-Specific Information on the Representative Depth to the Shallow Water Table for Soils In Vermont Using the NRCS Web Soil Survey.” (See Image #2, below.)

There are several different ways to use the NRCS Web Soil Survey, but it’s pretty easy to use the “Area of Interest” (AOI) tab to get you zeroed in on crystal clear aerial map, and then click the Soil Map tab to get the soil type overlay on the aerial map. Under the Soil Data Explorer tab is a sub-tab “Soil Properties and Qualities,” and then another sub-tab called “Water Features,” giving you “Depth to Water Table” for each soil type in your area of interest.

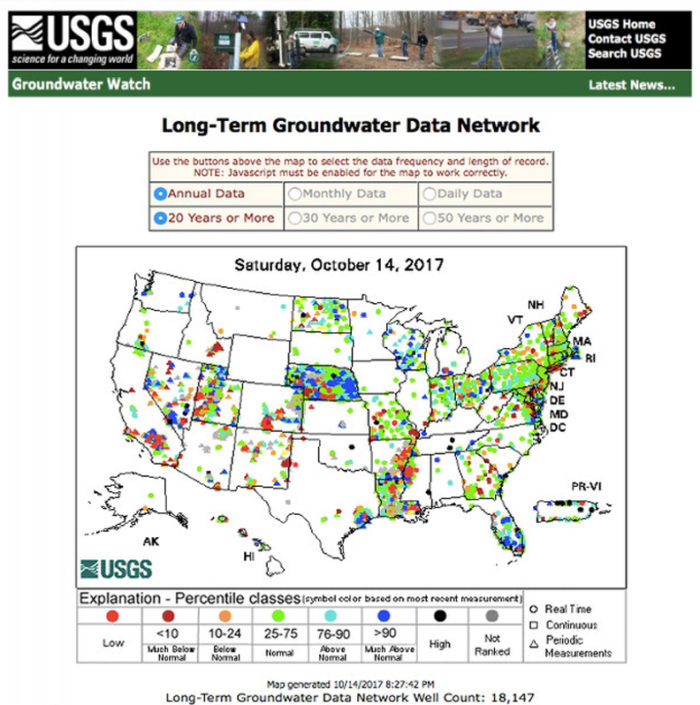

USGS Groundwater Watch

The U.S. Geologic Service has several databases related to ground water. (See the image at the top of the page.) For builders and remodelers, the most useful of these resources are probably the Active Groundwater Level Network and the Long-term Groundwater Data Network.

Each is fed by records from over 850,000 wells drilled over the last 100 years. The data are pretty thin for Vermont and probably for other sparsely populated areas, but there’s tons of data for many highly populated regions of the U.S.

Local historical societies and the Library of Congress

Trying to piece together just why our section of Fairview Street in Brattleboro is a rarity — flat, with tons of fill — I got help at the Brattleboro Historical Society (BHS). I was directed to a web site called Old-Maps.com, where I found a great resource, “Early Maps of Brattleboro” (see Image #3, below). This narrated collection of maps explains a lot about local land use, but strangely, very little about our section of Brattleboro.

A quick trip to the BHS led to file cabinets full of street photos, and perhaps more importantly, to a volunteer — a neighbor of mine — who suggested a web site from the Library of Congress called Chronicling America (see Image #4, below).

Amazingly, this database has hundreds of local newspapers — all digitized — for the years extending from 1789 to 1925. You have to be patient, but searching based on your street name or family names you know to have lived in homes for more than one generation can sometimes lead to the history of your lot’s use.

And my volunteer historian neighbor said more: “The two guys in town who know the most about local geology and water tables are Steve Barrett [head of Public Works] and Dave Manning [owner of a prominent and long-time excavation company]. You should give them a call.”

[Author’s note: I ran out of time to do a thorough search on Brattleboro newspapers and to talk with Dave Manning and Steve Barrett. But I will update on what they had to offer by posting their comments to this blog.]

Finally, in my research on ground water table information, I came across this great Foundation Checklist from the book, “Basic Engineering for Builders” (see Image #5, below). A great resource to wrap up this survey of information resources to keep your basements dry.

In addition to acting as GBA’s technical director, Peter Yost is the Vice President for Technical Services at BuildingGreen in Brattleboro, Vermont. He has been building, researching, teaching, writing, and consulting on high-performance homes for more than twenty years. An experienced trainer and consultant, he’s been recognized as NAHB Educator of the Year. Do you have a building science puzzle? Contact Pete here. You can also sign up for BuildingGreen’s email newsletter to get a free report on insulation, as well as regular posts from Peter.

5 Comments

I'm surprised builders aren't

I'm surprised builders aren't more interested getting this kind of information aggregated into some kind of GIS system, as well as filling in the gaps in it.

Due to your lack of time (one sympathizes) you may have stumbled on an good idea. Consider a "Building Science Mystery" series and release it serial, so people have to come back for the exciting conclusion.

"What do I need to do to

"What do I need to do to avoid basement water problems?" is an important question, but I don't think that any wide area data can provide an accurate answer. For example, my neighbor has a slow spring under his slab, requiring multiple sumps and a generator for backup power. I don't even need a sump.

WaterbTables

I'm sure there are areas, like long-settled Vermont, where you can get a lot of fairly good data to suggest what you will find. But like Jon, my experience building in rural areas in the PNW, is that conditions vary on a lot based on where you dig.

We rarely go deeper than necessary for a crawlspace, but particularly on sloped lots, the presence of springs, whether we hit rock , hard-pan or soil - are all so specific to the excavation that half the house may sit on one and half on another. It's going to be a long tome before accurate mapping will be useful here.

online maps versus site empirical data

I completely agree that online soil and geologic maps provide broad guidance so they can be useful for erring on the side of caution but nothing replaces what you find on the site. On our lot and house, the fact that a local excavator dug a drywall to manage site water for our driveway and found free-draining deep soil matched the soil maps--always good news to get that empirical confirmation.

Chronicling America and my review of local newspapers

I spent about 3 hours searching our local papers from early 20th century to try and learn more about why are stretch of Fairview St. is flat and full of fill, but came up empty. And when I finally got a hold of our local and longtime excavator Dave Manning, he said, "Sorry I can 't tell you more, Pete; sometimes you just get lucky."

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in