Image Credit: Images #1 and #2: Peter Yost

Image Credit: Images #1 and #2: Peter Yost A home inspector told my client that this mold in her attic was the result of insufficient ventilation. But the pattern is targeted and distinct, not generalized throughout the attic. This sure looked like the result of an air leak to me, as indeed it turned out to be.

Just about every week, I get a call or an email that turns into a building science puzzle. While the problems are varied, how you solve them doesn’t change.

First, you understand how heat and moisture move through building assemblies. Second, you follow the advice of your spouse.

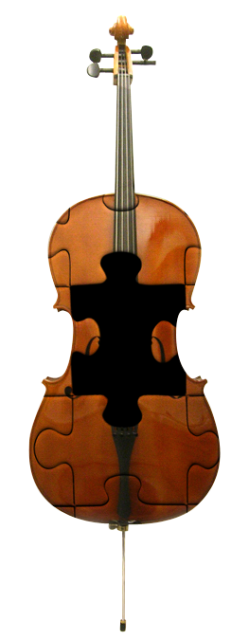

My wife of 27 years is a real master at jigsaw puzzles, and she would laugh to learn that I think of myself as a puzzle master of any sort, since I am useless at the jigsaw ones. But she completely agrees that I should use her method of solving jigsaw puzzles in my work on building science problems.

Here is the dovetail between her jigsaw and my building science puzzling.

Step 1: Assume nothing

- Jigsaw: Make sure you have all the puzzle pieces.

- Building Science: Make sure you have all of the information you need about the building and the problem.

It’s almost funny how hard it can be to get folks to provide complete information; many want to stay focused on the expression of the problem and not “waste time” on full context. The easiest way to get the puzzle wrong is to “solve” it without all the pieces.

Step 2: Establish boundaries

This means separating out elements of the building that pertain to the problem at hand. Sometimes this is about collecting measurements or doing inspections to complete the “edges” of the building science problem at hand.

Can you imagine doing a jigsaw puzzle while blindfolded? Surprisingly, I have completed quite a few building science puzzles without ever visiting the project. I can only do this when I have confidence in the client’s abilities and willingness to send lots of images and accurate measurements.

Step 3: Find patterns

- Jigsaw: Group interior puzzle pieces by colors and patterns.

- Building Science: Use the puzzle clues to characterize heat and moisture flows.

Invariably, the client wants to focus on the spot where the moisture problem is being expressed. But you need to start with finding the source of the moisture. The pattern of the moisture expression can be linked to the wetting mechanism — bulk water, wicking, air leaks, or diffusion. The pattern could be visual or based on multiple measurements.

Step 4: Zoom out

- Jigsaw: Flip back and forth from focused detail to big picture puzzling.

- Building Science: Switch between building-level to site- and climate-level considerations.

No matter where you have set the boundary conditions for each project, it’s a good idea to step back and consider what role, if any, the site or climate could play in the building science puzzle.

Step 5: Cheat

- Jigsaw: Use the picture on the box. (It’s not cheating!)

- Building Science: Compare the puzzle at hand to similar puzzles you have solved.

Step 6: Solve so you can savor

- Jigsaw: Savor dropping in that last piece.

- Building Science: The real last piece is finding the source.

It is possible to “solve” the building science puzzle without ever identifying its source. But if that’s your approach, there is always one missing piece at the end, and that should drive you crazy till you drop it in. It’s also what keeps you from being called back days, months, or even years later by a less-than-happy client.

At the house shown in the photo at the top of the page, there were two distinct mold blooms that exactly coincided with uninsulated and un-air-sealed kneewall doors (see Image #2, below). We “solved” the problem of warm, moist air leaking into the attic through these doors during the winter by doing a blower door-guided air-sealing package for the whole home.

But the mold spots in the attic were pretty intense, so I thought I should follow up with the homeowner about interior relative humidity levels during the winter. They intentionally maintain it at about 55%. I was shocked: that’s very high for winter in their climate.

The homeowners, I discovered, are musicians and need to protect their harpsichord and cello through the dry season. Learning the real source of the moisture led to a more thorough conversation about how to protect both their instruments and their home.

I savored fitting that last piece into place.

In addition to acting as GBA’s technical director, Peter Yost is the Vice President for Technical Services at BuildingGreen in Brattleboro, Vermont. He has been building, researching, teaching, writing, and consulting on high-performance homes for more than twenty years. An experienced trainer and consultant, he’s been recognized as NAHB Educator of the Year. Do you have a building science puzzle? Contact Pete here. You can also sign up for BuildingGreen’s email newsletter to get a free report on avoiding toxic insulation, as well as regular posts from Peter.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

5 Comments

Humidifying to 55% isn't good for the house OR the occupants!

55% relative humidity is even above the optimum human healthy range.

Most health care professionals recommend keeping it between 30% & 50% relative humidity. (Even though ASHRAE used to recommend 40%-60%, or even 25%-65%, they're wrong.) Going above 50% allows dust mites to thrive, increases the prevalence of fungal infections of skin & lungs, and increases risk of bacterial infections. While 55% isn't risky for most individuals (even 60% is fine most who are not allergic to dust mites), there's no point to maintaining it that high, and it's not really optimal.

Keeping a house at 55% RH all winter in a colder climate will raise the springtime mold spore counts by quite a bit, due to the increased moisture content of the structure, which becomes an aggravating factor for asthma and those allergic to molds.

not always as tidy as it sounds

Peter,

It sounds like you mostly put together puzzles that are fresh from the store shelf, with the shrink wrap still on the box at the beginning. Maybe it's just that I'm not as good at assembling the pieces as you are, but the building science puzzles I deal with don't seem as neat and tidy as yours. I seem to deal with more puzzles that are missing pieces, that have pieces from other puzzles mixed in, that are missing the box cover with the picture on it. I often don't get the satisfaction of putting that last piece in. So we frequently have to make a guess at the root cause, implement some measures that we're pretty sure will mitigate the symptoms, and monitor the results to see if we guessed well enough. Not nearly as fun as your analogy.

Paul

observation

Why do the two photos provided not seem to match the house in the picture or does the other side of the house shown have a steep pitched addition that would coincide with the attic picture?

keeping RH at 55%

You are right Dana - and in fact, I spent some time with the client on this issue and the need to avoid RH this high. They were not really set on that number; it's just that as they don't air condition in the summer, that RH seemed to work best year round for their instruments, as an approximate target. And the hygrometer they were using was not all that accurate, as it turns out so they were plus or minus 5% (and yes, PLUS 5 would not be good) anyway.

not always as tidy as it sounds

I like the way that you have improved the analogy of jig saw and building science puzzles, Paul. Yeah, rarely if ever this tidy.

I did leave some "pieces" out: like the fact that the home inspector took a look at the attic and told the client that the mold was the result of too little attic ventilation, recommending a gable end exhaust fan to increase ventilation. And yes, that would have made the air leakage and mold WORSE! Or the unusual pattern of lichen and moss on the north side of the home, which I thought might correlate to the location of the attic mold blooms but turned out to be related to the leaching of zinc from the chimney flashing.

Future puzzles won't be so "pat."

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in