Image Credit: Image #1: U.S. National Library of Medicine - Public domain

I’ve been reading a lot of BS lately. No, I’m not talking about blood sugar. It’s brain science that’s captured my attention: understanding how the human brain works, why we do the things we do, and what common illusions often lead us astray.

What I want to talk to you about today, though, is foam insulation and global warming. But first, we have to talk about calamari.

Have some calamari

This has nothing to do with any visual similarity between calamari tentacles and grey matter. Instead, let me relate a story first told on This American Life in 2013. Let’s say you go to a restaurant and order fried calamari. The server brings it and you and your friends start munching away. Well, all but one of you anyway.

Your friend Kim is just sitting there, not partaking of the fried delicacy you’re all enjoying so much. Even worse, he’s grimacing while watching the rest of you eat. So you ask him what’s up … and then you wish you hadn’t.

Calamari served in restaurants, he tells you, is often not calamari at all. It’s really hog rectum! Farmers package it as imitation calamari and that’s what a lot of restaurants serve now, he says.

Disgusting, right? A lot of people who have heard that story, first taken mainstream on that 2013 This American Life episode, think so. The truth, however, is that there’s really no evidence to support that claim. It’s an urban legend. So will you eat calamari tonight?

I’ll come back to the calamari in a bit, but first let’s look at foam insulation and global warming. I promise that everything will make sense when I’m done here.

Foam insulation and global warming

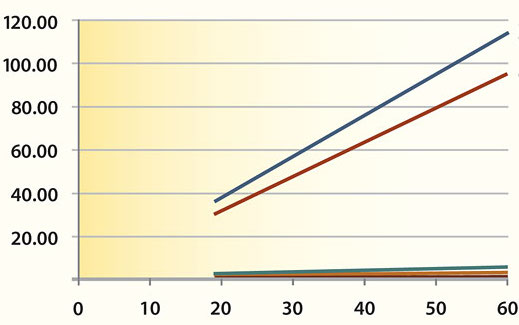

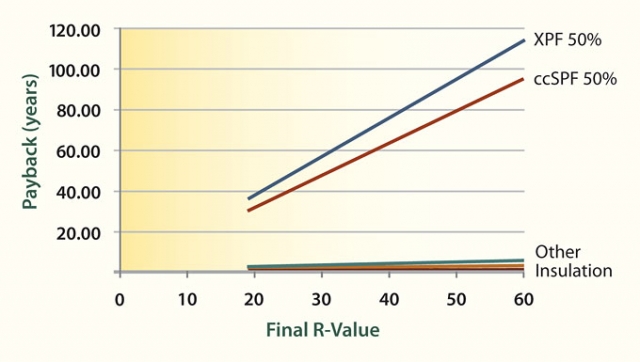

Last November I was at a conference when one of the speakers showed a graph with the same data you see below. In the graph, you can see two lines way above the others. And they increase rapidly, whereas the other lines are much flatter.

The graph above comes from Alex Wilson’s article, Avoiding the Global Warming Impact of Insulation. In it he showed results from calculations of the “payback” of various types of insulation. It wasn’t financial payback, though. He wanted to know how long it would take for insulation to save enough energy to offset the global warming impact of the insulation itself.

Here’s an easier way to understand it. Using insulation saves energy. (Duh!) Saving energy means power plants put less greenhouse gas into the atmosphere. But insulation takes energy to make, too. That’s the embodied energy. And some types of insulation use greenhouse gases that can escape into the atmosphere.

Wilson wanted to quantify the relationship between greenhouse gases prevented and greenhouse gases emitted. You can read his article and see a summary of what they did. The graph below is perhaps the main result. It’s the same graph as above with the labels included this time. Payback is on the vertical axis, and lower is better.

“Assumptions are key in this analysis”

When I first read Wilson’s article in 2010, I thought that I must have missed something. So I read it again, more thoroughly. I still didn’t see how he got from point A to point B. Even after reading the full article, I just didn’t think it held up.

The main problem is they had to assume too much. With a different but reasonable set of assumptions, their results would have looked far different from what they showed. But hey, they told readers upfront that the results didn’t really mean much when they said, “Assumptions are key in this analysis.”

A few months after Wilson published his article, I wrote a response titled, Don’t Forget the Science in Building Science. In it I laid out the assumptions:

- The manufacturers used high GWP blowing agents.

- The offgassing profile is uniform.

- The lifetime of the product is somewhere between 50 and 500 years, though the article doesn’t say what numbers they used.

You can go back and read my article for more on my original criticism. The main point is that they really had only one bit of information. It was a guess because manufacturers were tight-lipped about exactly which blowing agents they were using, but it was a good guess.

Blowing agents and global warming

Really, it all came down to the blowing agents used in the foam insulation materials. That’s the stuff that turns the liquid chemicals into a foam. Global warming potential (GWP) of various materials is a number that refers to carbon dioxide. For example, methane has a GWP of about 36 over a 100 year time horizon. That means it can trap 36 times more heat than the same mass of carbon dioxide.

At the time Wilson wrote his article, most closed cell spray foam was probably using HFC-245fa as the blowing agent. Its GWP is about 1,000. XPS probably used HFC-134a, with a GWP of about 1400. The other foams use water or pentane as blowing agents, and they have much lower GWPs.

In the calculations Wilson reported, the embodied energy of the various insulation materials had little effect on the payback. The biggest factor was the emission of high GWP blowing agents. (Again, those results were based heavily on the assumptions they chose.) That’s why the ccSPF and XPS lines were so far above the rest.

The times they are a changin’, though. Honeywell has a low GWP blowing agent called Solstice. It has a GWP of less than 5. At the Spray Polyurethane Foam Alliance conference last month, I heard that at least one of the big spray foam companies (Lapolla) is using it. More are sure to follow.

The calamari connection

Now, let’s wrap this up by getting back to calamari and brains. Researchers have documented that when we’re given bad information, we believe it. And when we’re told later that the information was wrong, we still believe it. How many jurors do you think really disregarded a specious comment from a defense lawyer just because the judge told them to?

I haven’t had calamari since I first heard the hog rectum rumor. I’m sure many others have done likewise. Our brains hold onto the initial information, even when it’s shown to be wrong later.

As I said, I’ve seen this bad information about closed cell spray foam and XPS foam board come up many times in the last six years. I’ve spoken up whenever I could to attempt to get people to understand they shouldn’t base decisions on that misleading graph.

Yes, those two types of insulation probably used — and some still use — blowing agents with high global warming potentials. That’s really as far as you can go quantitatively, though. We just don’t have enough data to make the kind of pronouncement that Wilson did.

The brain likes to hold onto those things that get there first. Even when they’re shown later to be wrong. Even when the one thing those products were guilty of becomes no longer true as foam manufacturers switch to low GWP blowing agents.

I’m going to have some calamari this week. How about you?

Allison Bailes of Decatur, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, energy consultant, RESNET-certified trainer, and the author of the Energy Vanguard Blog. Check out his in-depth course, Mastering Building Science at Heatspring Learning Institute, and follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

40 Comments

"Bogus," "bad information," "false"?

Allison,

You haven't proven your allegations that Alex Wilson provided "bad information" that is "bogus" or "false."

Alex Wilson presented some calculations based on the best information available. Not all of the information was certain; for the uncertain factors, Wilson made some assumptions, which he explained. Wilson based his assumptions on valid principles.

Uncertainty exists in many scientific fields. As long as the basis for any assumptions is explained, the reported calculations aren't "bogus" or "false." They're simply the best conclusions that can be made with the available data.

[P.S. In Comment #29 below, the author of this article, Allison Bailes, apologizes to Alex Wilson. In his comment, Allison writes, “I've updated the article and a comment to remove my claims that Alex Wilson's article was ‘bogus,’ ‘false,’ and ‘pseudo-scientific.’ ”]

?

I have no idea who is right, but I find it kind of funny that a debate over the hard science behind global warming would have to rely on some rather soft psychological research into why people might act the way they do.

Let's talk about uncertainty

Yes, Martin, scientific results always have their associated uncertainties. When I was writing peer-reviewed scientific articles, it was something we had to include with our results. Presenting results without also giving the uncertainty means that the results are no more valuable than opinion.

So where are the uncertainties associated with Wilson's results? He didn't give them. My whole contention here is that with all the assumptions he made, the uncertainties would have to be so high as to make the results meaningless. Conversations I've had with building scientists familiar with the work confirm my thoughts on that matter.

You wrote, "They're simply the best conclusions that can be made with the available data." If I did a heating & cooling load calculation for someone and I didn't collect information about what type of equipment they were going to use, how leaky the house was, or how much insulation was in the house, I could make assumptions and come up with results. When the system I designed based on that load calculation didn't work and the client sued, saying I gave them the best possible system based on the available data wouldn't hold up in court.

Response to Allison Bailes

Allison,

You wrote, "So where are the uncertainties associated with Wilson's results? He didn't give them."

I think your statement is flat-out wrong, as can be verified by reading his article, Avoiding the Global Warming Impact of Insulation.

To take just two examples:

1. Wilson wrote, "I'm not 100% sure that XPS is made with HFC-134a; manufacturers are unwilling to divulge the exact blowing agents they use, saying the information is proprietary, and material safety data sheets have not been updated yet to reflect the new blowing agents that were required as of January 1, 2010. But various hints in technical literature have led me to believe that this is the blowing agent being used."

2. Wilson wrote, "Some researchers, such as L.D. Danny Harvey, Ph.D., of the University of Toronto (who first raised the concern about the high GWP of foam insulation materials in a technical article a few years ago), has assumed that a large majority of the blowing agent leaks out over time, but based on conversations with technical experts in the industry, our analysis in Environmental Building News adopts a more conservative assumption that only 50% leaks out over the life of the insulation."

Other uncertainties are similarly explained.

You gave a hypothetical example of a case in which a consultant "didn't collect information about what type of equipment they were going to use, how leaky the house was, or how much insulation was in the house." If I were cross-examining the consultant in court, of course I would ask, "Were the specs for the equipment readily available? Why didn't you perform a blower-door test? Did you visit the attic to measure the insulation depth?"

You have provided no similar line of questioning to impugn Alex Wilson. His uncertainties are clearly listed, and the uncertainties he lists are not as easily measured as the BTU/h rating of a furnace or the air-leakage rate of the envelope at 50 pascals of depressurization. They are unknowns, while the failures of the consultant in your example are failures to measure easily measured quantities.

That's not uncertainty

Martin, you seem not to understand the difference between assumptions and uncertainty. What you've done in your last comment is just restate Wilson's assumptions. Uncertainty is quantifiable. If I tell you that I've calculated a heat transfer of 1400 BTU, for example, I can also calculate an uncertainty associated with that number. If that uncertainty is 50 BTU, that shows me the result is pretty good. If the uncertainty is 1400 BTU, my result doesn't tell me much.

So again, where are the uncertainties associated with Wilson's results? He didn't give them. I'm sure they're very, very high.

Flat out wrong, eh?

So foam GWP is... an urban legend?

Martin's spot on. Alex contributed something valuable when he made a good faith attempt to evaluate the cost/benefit on foam. This is a squidicious critique--a cloud of ink and no substance behind it.

Maybe these companies are feeling pressure to improve their product on account of Alex's work and that pernicious graph?

"Where are the uncertainties?"

Allison,

You asked, "where are the uncertainties associated with Wilson's results?"

I provided two examples. One uncertainty is that we aren't sure which blowing agent is being used by foam manufacturers. Another uncertainty is that we aren't sure what percentage of the blowing agent in foam insulation is eventually released into the atmosphere.

It's disingenuous to say that Wilson didn't tell us about these uncertainties. He did. And, since Wilson told us about these uncertainties, it's disingenuous of you to say that his discussion of the issue (and his calculations) are "bogus" and "false."

At least one = No problem

I appreciate the concern for careful data collection and careful analysis. Yet in this article, Allison seems guilty of the criticisms that he levels at Alex. He admits that two widely used blowing agents have significant global warming potential (GWP). BUT, he tells us, as of last month, "at least one" company is using Honeywell's safer blowing agent, and "More are sure to follow." On this basis, he dismisses the calculations presented by Alex in 2010, and more recently. Allison indicates that belief in Alex's analysis is the equivalent of eating hog rectums.

Now if you think my previous sentence is a bit of a distortion, I agree. And "distortion" is exactly what Allison is trying to achieve with his digression about calamari. Worse yet, when he leaves the digression for science, he asserts that because better blowing agents will be used more widely in the future, an analysis of the GWP impact of foam using bad blowing agents, over the last five years, should be considered hogwash. Or perhaps calamari wash. A more credible title might be "Current and recent numbers are misleading when applied to a probable future".

Assumptions aren't uncertainties

Martin, you seem to have missed what I said. Uncertainty in science isn't a statement. It's a number. Why do you not understand that?

Response to Derek Roff

Alex Wilson wrote an article purporting to quantify the global warming impact of insulation. His results relied almost entirely on assumptions, which he himself admitted. He gave no quantitative uncertainties associated with his results.

In my article, I haven't presented quantitative results as being more meaningful than they are so how am I guilty of the same thing Wison is? I'm pointing out that his results are a lot less significant than many people have taken them to be. I've also pointed out the problem of bad information getting established.

Anyone who wants to believe these results is free to do so. I stand by my statement that Wilson's results are weak and have misled some people.

Response to Allison Bailes

Allison,

I disagree with your statement that "Uncertainty in science isn't a statement. It's a number."

Quoting from an article on "Uncertainty":

"Although the terms are used in various ways among the general public, many specialists in decision theory, statistics and other quantitative fields have defined uncertainty, risk, and their measurement as: Uncertainty: The lack of certainty. A state of having limited knowledge where it is impossible to exactly describe the existing state, a future outcome, or more than one possible outcome."

Science

Martin, you can continue defending your conflation of assumptions and uncertainty if you'd like. But science doesn't work that way. When a scientist publishes quantitative results, there are ALWAYS quantitative uncertainties associated with those results.

Anyone publishing quantitative results who wants to make sure they're credible will also provide the quantitative uncertainties. Wilson didn't do that. Each of the numbers he used in his calculations would have a quantitative uncertainty associated with it. Those quantitative uncertainties propagate through the calculation to yield the quantitative uncertainty in the result. Every introductory physics student learns how to do this.

So what are the quantitative uncertainties in Wilson's results? If he calculated a payback of 50 years plus/minus 100 years, how much would you believe that number?

Uncertainty & error

Martin, perhaps you'll understand better what I'm saying if you substitute the word "error" for "uncertainty." A lot of people use that term and distinguish between systematic and random errors. I prefer the term "uncertainty" to "random error" because it's not really an error. It's just the uncertainty you get from making measurements.

Response to Allison Bailes

Allison,

You asked, "If he calculated a payback of 50 years plus/minus 100 years, how much would you believe that number?"

I would believe the results he published to the same extent as I believed the results on the day that I first read them. That means that I considered his numbers to be the best possible effort to answer an important question. I knew that the answer contained uncertainties. But it still is a useful answer, because it allows green builders to weigh the risks of different insulation choices.

When it comes to climate change, we might want to know something about Alex Wilson's calculations, even if the calculations are based on assumptions that are uncertain -- because using cellulose insulation isn't particularly burdensome, and because the consequences of global climate change are potentially devastating.

Uncertainty & significance

Martin, we're going to have to agree to disagree here because you seem unwilling to accept how science works. If you say, "it still is a useful answer, because it allows green builders to weigh the risks of different insulation choices," if you knew the answer were 50 years +/- 100 years, you don't understand how the meaning of quantitative results. 50 years +/- 100 years means that the result could be 0. It could even be negative, which means that you're ahead before you even start. It could also mean 150 years.

How does that give anyone a basis for deciding whether to use or not use a particular insulation material? That range includes both the very good and the very bad results.

You seem to have an emotional attachment to Wilson's results. That's fine. But let's stop pretending the results really mean anything. Until Wilson shows us the quantitative uncertainties, we know nothing except that the the GWPs of the two blowing agents in question are very high. And those GWP numbers have quantitative uncertainties, too.

But really...

But really, the big question you both are studiously avoiding is how many angels exist on the head of a pin? I think there may be a hidden agenda causing you both to avoid this important question that is in the news everyday now. Oops, I meant a thousand years ago.

article on high performing assemblies relationship to GWP

Have you guys seen this article? http://www.constructionspecifier.com/understanding-highly-insulated-wall-assemblies-relationship-with-global-warming/

The author of this article

The author of this article writes in an email conversation with me: "even for the High GWP wall assembly, which contains 87 kg of CO2 in the insulation materials, the amount of GWP conserved due to the function of the insulation vastly outweighs the amount of GWP attributed to the insulation (by a factor of 20-60x). Ironically, the choice of heating energy source has a much greater impact on GWP emissions over the lifetime of the building than does the GWP content of the wall assembly". The reason the energy source makes such a big difference is the huge transmission losses of electricity make its GWP much greater than gas. Therefore when these wall systems are used when electricity is the source the GWP emissions reduction is greater.

Too much snark

Sorry to both of you for the excessive snark in my comment. I seem to have been in a worse mood than even I realized. Susan, that was a very interesting article. There seems to be something in the assumptions that have not been identified, but that are very relevant. I would like to know more about what they are and how they are made. One of my biggest questions is how does the author quantify the cost of transporting electricity and what is the efficiency loss per mile of line transmission. An answer to that would be very interesting to me.

Allison is correct...

...at least about uncertainty. Like him, I was also trained as a physicist, doctorate degree and all. I don't know who is correct on this GWP argument. There really is no way for ANYONE to know without seeing the calculations and how much uncertainty was assumed in each value (or constituent quantities) used in the equations used to get to the answer. But to give a poor primer on uncertainty, suppose some quantity X was equal to 10 times another quantity A, but A was only known to +/- 30% of its stated value. Lets say A had a stated value of 100. Well, a good scientist would report A = 100 +/- 30. This means A could be as low as 70 or as high as 130, a range of 60. That range is pretty large when you consider that the stated value of A is 100. (BTW, anytime you have error larger than a few percent, you have a significant problem.) Okay, if you accept that much, given X = 10 * A, what do the readers think the uncertainty in X is? I'm sure there's no surprise that the error in X is 10 times as much as the error in A or 300; thus, X=1000+/-300. That one was pretty straight forward. But, there are rules for adding uncertainties, multiplying uncertainties, dividing uncertainties, raising uncertainties to an exponent, etc. And when a physicist submits a paper for publication in a peer reviewed journal, if his/her paper relies on calculations of some quantity, he/she is expected to have gone through this process to come up with a quantifiable number for how reliable the calculation is. AND it doesn't matter how complicated the expression is to calculate or how many values (or constituent quantities) go into the calculation, there is a method to calculate the error or uncertainty in the final number. There are books devoted to the subject; I own one. I think the original author of that graph can clear all this up by showing Allison the equations and numbers he used for his calculations with uncertainties stated for each number and leave it to Allison to calculate the error bars for this graph.

And I signed up for a 10-day trial just to say that!

Closed cell foam with no GWP

Anybody interested in water blown closed cell foam should check out Green Insulation Technologies, We have been spraying their 2 pound foam for years and it works really well. The company is located in the Cleveland, OH, area and should be just a Google search away.

Response to Alex Wilson

You're right, Alex. I haven't said anything about Harvey's paper, and I'll make sure to do so soon. I read his paper in 2010 when all this started. I have some thoughts about that paper and how it relates to what you published. Don't have time to do anymore on it this week, but I'll definitely say more.

Red herrings

If all we had for insulation was HFC blown foam, green builders would need to study GWP payback time really closely, and think critically about what time horizon to design for. If they did that based on poor data, they'd end up with more global warming impact than they could have had with a differnet insulation level. So we would need to be really careful about designing insulation thickness based on accurate data.

But we have lots of alternatives without HFC blowing agents. More, in fact, than when Alex first raised this issue. So it doesn't really matter exactly how long the payback is. What matters is that the impact is not negligible. Given that the impact of the blowing agents can be substantial, the responsible choice is to avoid insulation that uses them. There's no question that the global warming impact of EPS, polyiso, or cellulose is much less than the impact of North American XPS or conventional ccSPF (ie., not Lapolla's 4G product).

The argument that alternative blowing agents make the concern obsolete will eventually, I hope, be true. But it's not time for that yet. The XPS industry sucessfully got the deadline for their use of high GWP blowing agents extended to 2021; and ccSPF does not yet have any phaseout regulation with a concerete deadline. If we get to a point where one can buy XPS in North America blown with low GWP gasses, choosing the low GWP version will become even more obviously the correct choice, rather than becoming an obsolete consideration.

As for the argument that we don't know what's actually being used, we do know: The XPS industry itself clearly states it in this document of theirs. http://www.xpsa.com/pdf/01%20-%20XPSA%20Industry%20Perspective%20on%20Sustainability%20and%20Environmental%20Awareness.pdf

And the EPA rulemaking document contains plenty more confirmation and data.

Allison's other blog posts, which are usually excellent, make recommendations without quantifying the benefits at all, much less putting physics-journal-ready error bars on them. Why is there suddenly a higher bar here?

GWP tool

Allison and everyone,

Here's a tool I wrote that might help address some of these issues. The sheet can be unlocked using the password "unlock", and you can see all the math behind it (all of it, with a couple of possible exceptions, taken from Harvey). More info in the notes on the first page.

Best,

David

[Editor's note: since David evidently forgot to provide the link, I'll provide it: David White's Excel spreadsheet. For more information on this topic, see Calculating the Global Warming Impact of Insulation.]

Bogus?

Allison, I can’t get all that worked up about Alex’s article. He fairly clearly states some of his assumptions and very clearly states the key one – that he doesn’t know for sure what blowing agents are used. Given that, any careful reader will know that his analysis is valid only while those assumptions apply. I’ve read thousands of refereed journal articles and written tens of them myself. This is often how most analyses go: state your assumptions, work out your calculations, then muse in the “conclusions” section of the refereed article about the “meta” aspect of the problem - when the assumptions don’t hold or get modified. It baffles me to hear that “science” demands a precise error bar on any numerical conclusion. It further baffles me that thought that the absence of said error analysis necessarily invalidates the conclusion or use of the calculations. It never has in my working life. Trends can be more important than precision in some cases. Error bars can be estimated, but there are even more assumptions buried in any error analysis that is even a little bit more than simple. For many problems it best not to go there – how do you put error bars on “not 100% sure that XPS is made with HFC-134a”?

Further, Alex’s conclusions are offered some amount of safe haven by the huge difference in the result: XPS and ccSPF are more than 10 times worse, by his metric, than the contenders (and 100 times worse than the best of them). That allows for a fair amount of error in his calculations and assumptions before his conclusion is rendered bogus. Alex states in his article “These differences are dramatic enough that, even if our assumptions are off by a significant factor, we can draw some general conclusions about sensible choices.” I couldn’t agree more.

You end your article above with a conclusion that, with new blowing agents, Alex’s analysis is soon to be rendered obsolete. I’ll bet that Alex would agree with that conclusion. There’s no news here. His article goes on at some length to discuss the effects of different blowing agents (pentane and water). Finally, you never state whether you think Alex’s conclusions are valid if you accept the assumptions as valid. You imply that you wouldn’t sign up for that – but I read Alex’s article and I would have to say that his analysis seems sufficiently sound that I would believe his conclusion any time that manufacturers use: (a) high GWP blowing agents, and (b) the off gassing profile is such that half of the gas ends up in the atmosphere in such a way that it contributes to global warming.

Finally, remember that assumptions are key in every analysis. We do not yet have a proven theory of everything and so we must always assume at the beginning in order to get to the end.

Oops

Thanks Martin. I meant to attach it, but I think I clicked one time too few. I think it will work this time...

DISSERVICE

Allison - After reading this article and all the comments, I have to conclude that you have done a disservice to this site and its readers. Most of us ( including myself) have accepted that XPS and ccSPF were to be avoided if other insulation materials would work. If you are going to attempt to discredit Alex Wilson's conclusions, you need to show us not just that his assumptions lead to bad science, but that the conclusions are wrong. Otherwise you're making a bunch of noise without useful information. What you are saying, in effect, is " Wilson might be wrong." Yes, but then you need to say," But Wilson might be right." Show us he's wrong, and we'll listen and evaluate your arguments and data. Until you can do that, don't bother questioning his methods or even his assumptions. What useful service does this achieve?

The science behind my article

Allison,

With your recent diatribe, as well as your earlier ones, I have not seen that you have ever responded to — or even referenced — the underlying peer-reviewed article from the August 2007 issue of "Building and Environment: The International Journal of Building Science and Its Applications," by L.D. Danny Harvey of the University of Toronto, upon which my article was based.

As a reminder, here's what I said in the original June 2010 Environmental Building News (EBN) article:

"Researcher Danny Harvey, Ph.D., of the University of Toronto, sounded the alarm about the climatic impacts of blowing agents used in certain foam insulation materials in a technical paper in the August 2007 issue of the journal Building and Environment. Daniel Bergey of Building Science Corporation presented a synopsis of Harvey’s research at the Northeast Sustainable Energy Association (NESEA) Building Energy Conference in March 2010.

"With the help of Bergey and John Straube, Ph.D., P.Eng., of Building Science Corporation, EBN reexamined the assumptions Harvey used, included new information about the blowing agents in use today (which differ from what Harvey assumed), and calculated the payback on the lifetime global warming potential (GWP) of insulation materials."

In fact, as explained in the article, I used more conservative assumptions in my analysis.

Having been trained as a scientist and with a degree in biology, I take offense at your continuing claims that I somehow sidestepped science. In my analysis, I started with Dr. Harvey's 21-page article (which you access by scrolling down to published paper #55 in his website: http://faculty.geog.utoronto.ca/Harvey/Harvey/publications.htm). Then, as a journalist, I sought to make Harvey's key points understandable to non-scientists.

As noted in the above excerpt from my EBN article, I sought to simplify that highly technical article as well as update it to more accurately portray the blowing agents in use. Because the issues are complex, I sought input of Dr. John Straube and Daniel Bergey, then of Building Science Corporation, in reviewing my conclusions.

Finally, as for Allison's comment about the characteristics of foams changing, he is absolutely correct. Here are a few more excerpts from my original 2010 EBN article:

"Manufacturers are working to develop and deploy fourth-generation blowing agents that have zero or very low GWP while still providing the various performance and safety properties that are required. Such developments would alter the conclusions of this article. Both Dupont and Honeywell are working on hydrofluoroalefin (HFO) blowing agents....

"When these new products replace the HFC-blown insulations in the coming years, the argument for avoiding SPF and XPS on the basis of lifetime GWP should largely disappear. By then, manufacturers may also have replaced the halogenated flame retardants with safer compounds. Until that time, however, there are good reasons to limit use of XPS and closed-cell SPF."

-Alex Wilson

An update

I went too far. I've updated the article and a comment to remove my claims that Alex Wilson's article was "bogus," "false," and "pseudo-scientific." I still disagree with some aspects of what he's done and think that what he published has misled people on choosing insulation. I know his intentions were good and he wasn’t trying to mislead anyone, though. I’ll publish a followup article with more about this topic soon.

I apologize to Alex Wilson. I went too far in my criticism.

Hang in there.

I am sorry to see your partial retraction and do not think you deserved the abuse heaped on you for what I thought was a well reasoned article. Wilson's study may have accelerated the development of low GWP blowing agents and that would be a very positive result. But it was not a very good example of good science. His conclusions resulted in the vilification of all foam insulation which continues today. Really, it was the blowing agents that should have been vilified. With the right blowing agent, foam insulation can be a very useful green building product but a lot of builders won't even consider it.

What's left?

Are the blowing agents presently used in manufacturing most foam the only thing that characterizes it as a "none-green" material, or are there other concerns with using it? The basic ingredients? The lack of bio-degradability?

I'm confused

Can I eat calamari? Or does it contribute to global warming?

Response to Buzz Burger

Buzz,

"I am sorry to see your partial retraction .... Really, it was the blowing agents that should have been vilified."

I think everyone involved in this discussion, including Alex Wilson, agrees that this discussion centers on the global warming effect of the blowing agents. The article that Allison criticized did not advocate that builders avoid all types of spray foam -- only those with blowing agents with a high global warming potential.

Response to Martin Holladay.

"I think everyone involved in this discussion, including Alex Wilson, agrees that this discussion centers on the global warming effect of the blowing agents. The article that Allison criticized did not advocate that builders avoid all types of spray foam -- only those with blowing agents with a high global warming potential."

True, but there are still a lot of people that unfortunately put all foam insulation in the same bag and avoid it.

Alex Wilson on XPS blowing agent at BE16

Just a few days ago at NESEA's BuildingEnergy conference I attended a session on March 9th about Life Cycle Analysis and Material Selections. After some discussion about the GWP of foam and XPS in particular, Alex Wilson who was in the audience stated that the blowing agent in XPS has been changed and the GWP is dramatically lower now. He seemed to imply that the GWP is now a non-issue with XPS. This was news to me. Was he referring to a past change in blowing agents that made some partial improvement or a recent dramatic switch that just happened?

Response to Lillian Maurer

Perhaps Alex will clarify what his comment actually was, but the situation is that the XPS industry is working on changing over to low GWP blowing agents, but they aren't there yet--it will probably be another few years at least. They fought really hard to get the deadline extended vs. the Jan 2017 deadline the EPA had proposed. The deadline for XPS insulation is now 2021. I'm sure that whoever has it available first will make plenty of noise about it. Perhaps in two years it will be available from some sources, and in four years from most sources.

Owens-corning did change to a mixture that has 2X lower GWP already, but it's still circa 700X the effect of CO2, or a hundred times worse than EPS, so although that helps it doesn't make it a non-issue.

In Europe, XPS is now blown with CO2, so it's possible that he was referring to Europe. Dow now makes a version with graphite in it (like NeoPor EPS) that has an R-value similar to the HFC-blown XPS, which undercuts their previous argument that CO2-blown XPS wouldn't meet the needs for R-value/inch in the US. http://www.dow.com/en-us/markets-and-solutions/products/xenergyextrudedpolystyreneinsulation/xenergy

The biggest recent recent change has been the availability of low GWP spray foam, from Lapolla. Demilac says they will have it available soon, but they don't yet. So a consumer who wants it in spray foam can get it, but that doens't make it a non-issue--you have to ask for it and verify that it is really what's used. And the spray foam industry protested even louder than the XPS industry, and the EPA didn't set a deadline for them to phase it out at all, so we'll continue to have high GWP spray foam in wide use for the foreseeable future.

One other piece of news is that, as of Nov. 2015, the Montreal Protocol parties agreed to the concept of a phaseout of HFCs, and they are working on the actual agreement. The agreement is scheduled to be completed this year (2016), but the timetable of phaseout is not yet established. The next meeting is in Geneva in April.

Response to Lillian Maurer

What I said in the session on LCA was that the issue of ozone depletion had been solved. Getting rid of CFCs and then HCFCs were huge triumphs of the XPS and polyiso industries, for which they deserve credit, and I mentioned that in the Q&A portion of the session. One of the speakers had reported that XPS does poorly in terms of ozone depletion, and I challenged him on that.

As Charlie Sullivan notes, similar progress has not been made relative to global warming potential for XPS, where HFC-134a is still used in all U.S. product. The closed-cell SPF industry, on the other hand, is now making great progress at replacing HFC-245fa with an HFO blowing agent with a negligible GWP. The polyiso industry shifted to hydrocarbon blowing agents some years ago, thus solving their GWP problem.

Response to Charlie Sullivan & Alex Wilson

Thank you both for your clarifying points.

In the avalanche of information I took in at BE16, those distinctions got fuzzy.

Keep up the great work Alex.

Dan - it doesn't but you will after you eat it.

Dan - it doesn't but you will after you eat it.

4 1/2 years later XPS manufacturers want you to know that their blowing agents do not contribute to the ozone depletion. If any were using using HFOs (Solstice) you can be sure they would be highlighting that too. But they do not.

A recent exchange with someone more involved in insulation suggested this was finally going change in late 2021. They are Canadian and likely more optimistic.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in