Image Credit: Image #1: Energy Vanguard - All other images: Marcus Jablonka

A water-resistive barrier (WRB) provides protection against water damage for water that gets behind the cladding of a building. But what if it doesn’t really resist water? I’ve written a lot about installation problems that can lead to compromised water resistance. (See the article I wrote last week, for example.) But other factors can make them leaky, too. Too much exposure to ultraviolet (UV) light is one of them.

At the Air Barrier Association of America conference in Baltimore last month, I attended a presentation by Marcus Jablonka of Cosella-Dörken. [Editor’s note: Cosella-Dörken is a manufacturer of water-resistive barriers.] The manufacturer has done a study of UV exposure to different WRBs, and the results should be of great concern to all builders, architects, and product specifiers. This is a preliminary study and there are still a lot of questions to be answered, but I’d be concerned if I were a builder.

A short primer on water-resistive barriers

As mentioned above, the WRB’s purpose is to allow water that gets behind the cladding to drain down and be removed from the building. They come in different flavors and have a variety of properties. First, you can get your WRB as a material that is:

- felt-based

- paper-based

- polymeric-based

Some properties are more important than others. Building enclosure control freaks understand that you need to control the flows of heat, air, and moisture to have a building that functions well. Controlling heat is typically not done by WRBs (although it can be), so let’s focus on liquid water, air, and water vapor.

No matter which WRB type you choose, you want it to have a high water resistance. Yes, I really said that. As obvious as it seems, sometimes it’s good to state — and question — the obvious. Without water resistance, a WRB has no WR so it’s not a B.

Some WRBs also have good air resistance, which means they can be part of your air barrier system. If you can do both jobs with the same material, so much the better.

Finally, we know now that it’s typically more important for buildings to have good drying potential than it is to put in materials with a low vapor permeance. Vapor retarders, especially Class 1 vapor retarders with a permeance of 0.1 or less, can reduce the drying potential and cause problems. Yes, you can design a building assembly to work with vapor-impermeable materials, but if you’re using WRBs without exterior insulation, it’s best to go with vapor-permeable materials.

Does your WRB get sunburned?

Exposure to ultraviolet light happens on job sites. Once you get the WRB installed, it’s sitting out there exposed to sunlight. Even on cloudy days, it gets UV exposure. (Ever gotten a sunburn on a cloudy day? I have.) The longer it sits there, the more it gets. But UV exposure also varies by location. Miami and Phoenix get a lot more than Seattle or Toronto. And it varies by time of year. Leaving a WRB exposed in winter won’t be as bad as leaving it out in summer.

In his presentation, Jablonka showed the results of UV exposure to self-adhered (peel-and-stick) WRBs and mechanically fastened WRBs. They took the different types of WRBs and did accelerating aging studies with UV lamps. They tested them for strength, elongation, and water resistance at three stages: before UV exposure, after 500 hours, and after 1,000 hours.

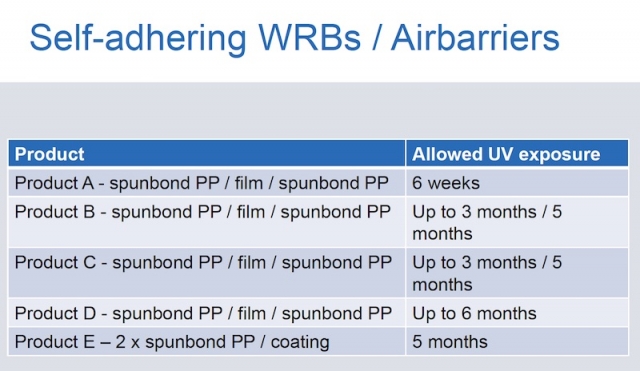

Here are the descriptions of the five self-adhered WRBs they tested.

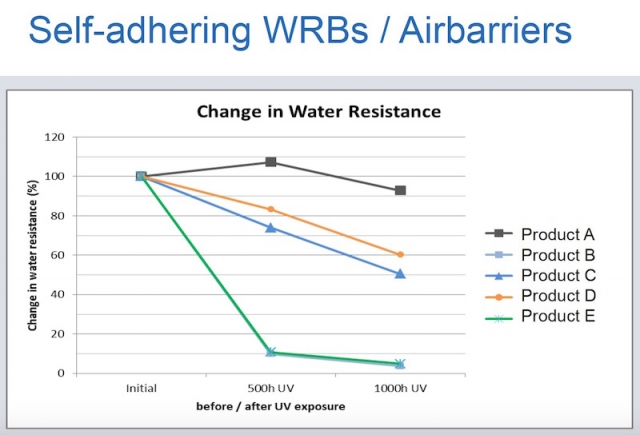

And here are the results for water resistance after the UV exposure (see graph at right).

That should be of concern to builders who use self-adhered WRBs. Two of the ones they tested (B and E) lost over 90% of their water resistance. Even at the intermediate stage of 500 hours, they’d already lost 90%.

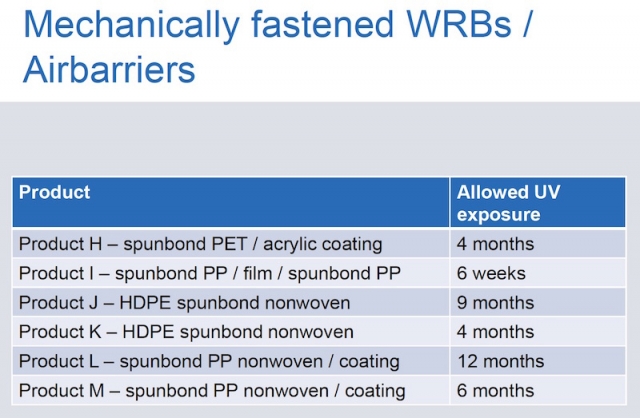

What about the mechanically-fastened WRBs? They studied six products in that category, as described in the table at right.

And here’s what happened to the water resistance (see graph at right).

Again, the results show significant degradation of one of the most important properties of WRBs. If I’m a builder, I don’t want a WRB that’s going to lose most of its ability to resist water.

Your WRB is showing

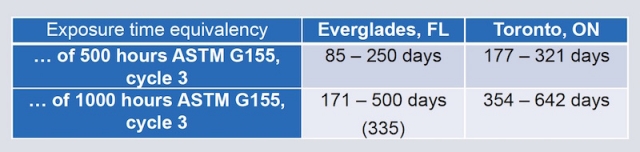

Of course, one of the key factors here is real-world exposure. The table below shows how exposure from the UV lamp relates to real-world exposure.

Five hundred hours of exposure to the lamp could be equivalent to as little as about 3 months exposure in south Florida or as long as 11 months in Toronto. One thousand hours of UV lamp exposure equates roughly to as little as 6 months in Florida or as long as 22 months in Toronto.

There probably aren’t many projects that leave the WRB exposed for two years. Three months, though, does happen occasionally. If you were using product B or E of the peel-and-sticks or product L of the mechanically-fastened, even at the 500 hour stage, the water resistance is down 90% for the former and 50% for the latter. So how much would it be down after one month? Two months?

Also, note that products B and E are labeled as having allowable exposures of 5 months, and the manufacturer of product L says you can leave it exposed for up to 12 months. After seeing these data, I wouldn’t be willing to take that risk.

Conclusions

This study raises some questions. If some products do so poorly in an accelerated aging study, will they show similar degradation under normal conditions? How long can you safely leave a WRB exposed? Although there are standards for water resistance, strength, and other WRB properties, there’s not any required testing for allowable UV exposure.

It’s too early to say how much of a problem UV exposure might be to the water resistance of WRBs in the real world. More research, especially with sun exposure on products left exposed outdoors for various amounts of time, can shed some light on this.

The best thing builders can do to prevent problems from UV exposure is to get the WRB covered up as soon as you can. As you can see in the data above, even being left exposed for three months in Miami can cause a big drop in water resistance of some products. Just because some manufacturers claim their WRBs can be left exposed for 3 months or 5 months or 12 months doesn’t make it true.

Jablonka has made his results available to anyone who wants to see more of the details. Click below to download the full set of slides and the paper:

Allison Bailes of Decatur, Georgia, is a speaker, writer, energy consultant, RESNET-certified trainer, and the author of the Energy Vanguard Blog. Check out his in-depth course, Mastering Building Science at Heatspring Learning Institute, and follow him on Twitter at @EnergyVanguard.

Weekly Newsletter

Get building science and energy efficiency advice, plus special offers, in your inbox.

4 Comments

Brittle WRBs

Is this the first study done on the affects of UV on WRBs? I thought this was a pretty well known property of WRBs. I don't know how many times I have removed siding to find Tyvek that had no tensile or tear strength left. It was very brittle and while I didn't do any water or air permeability tests I doubt they would be flattering. This was over ten years ago when I was in the siding trade. That would mean the Tyvek was installed long before that. I have no Idea if the manufacturing formula, or process has changed over the years. And off course it is impossible to tell if the WRB was exposed to the sun long before it was sided over. I live in Oswego County NY which is not the wealthiest of communitites. My friends at work who are not from around hear call Tyvek Oswego County siding. I imaging some of these homes my friends joke of will someday be sided right over the Tyvek that has been exposed for years. Then someone might strip that siding off and ponder of the products qualities. Of course I just built my garage using OSB covered with tyvek, then a rainscreen and LP smart products. I covered most of the WRB withing two months since I decided to start siding by myself in December. Then there is the cupola which hasn't been sided for four months now since I would rather risk water intrusion than breaking my leg from falling on the steel roof that still has a little snow on it today. Not to mention it feels as though the sun hasn't been around in five months so I will probably be alright.

What about UV through the siding?

Some siding lets some light through. I don't know if any UV gets through or not. If 90% of the UV is filtered out, after the siding is in place, then the WRB could get the equivalent of 500 hours of UV lamp exposure in about three years, for a site in Florida or Arizona (calculating from your charts). Is this of any concern, or does all siding block all the UV? Has any testing been done on heat exposure, without UV? I would think that a WRB in Phoenix behind dark vinyl siding might experience very high temperatures.

I notice that the chart labeled "Self-Adhering WRBs/Air Barriers - Change in Water Resistance" appears to omit a line on the graph for product B. Looking at the link to Jablonka's slides, I can see that product B and product E have identical graphs. That wasn't visible to me on the lower resolution image on this page.

Response to Derek Roff

Derek,

The only type of siding that I know of that lets a significant amount of UV light penetrate to reach the WRB is so-called open-joint cladding (see photo below). I don't think that this type of cladding makes any sense, but there is no accounting for taste.

Cosella-Dörken, the WRB manufacturer that employs Marcus Jablonka, promotes a WRB designed for use behind open-joint cladding. The WRB is called Fassade S, and you can read more about it here: New Green Building Products — September 2010.

The fact that Cosella-Dörken paid for this research is either (a) admirable, because it furthers human knowledge about WRBs, or (b) indicative that we should be skeptical of the results, because the sponsors of the research have a financial interest in the study's results. Depending on your level of cynicism, you can choose either (a) or (b).

.

Thank you, Martin.

I appreciate your taking the time to answer my question.

Log in or create an account to post a comment.

Sign up Log in